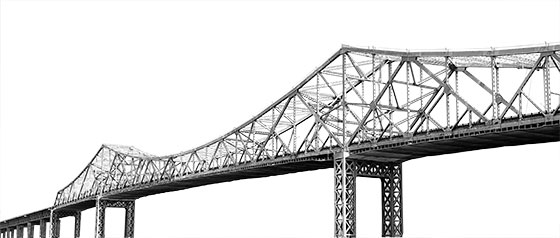

A few years ago, Barry LePatner, a construction attorney and nationally renowned infrastructure expert, gave a speech up in Rockland County in which he discussed the nearby Tappan Zee Bridge. Built 58 years ago, the three-mile-long span, which crosses the Hudson River from South Nyack to Tarrytown in Westchester County, is one of the region’s busiest and most vital roadways—a major passenger and trucking route connecting New York and points west to New England that allows vehicles to skirt the gridlock of the Greater New York metropolitan area. The Tappan Zee, LePatner told the assembled crowd of New York State finance officials, is also one of the most decrepit, and potentially dangerous, bridges in the country.

LePatner, who is the author of a book called Too Big to Fall and who routinely offers dire warnings about the condition of America’s vital infrastructure, considers the Tappan Zee his “scary of scaries.” Yet even he was taken aback when, after the speech, a state official sidled up and implied that things were worse, even, than LePatner imagined. The man asked LePatner how often he crosses the bridge. Maybe twice a year, LePatner told him, to go antiquing in Nyack. “That’s enough,” the official replied.

For the record, the New York State Thruway Authority, which controls the Tappan Zee, insists the bridge is in no immediate danger of falling down. But the 140,000 or so people who travel daily across the seven-lane span, which was built to handle a fraction of that traffic load, can be forgiven for having their doubts. The Tappan Zee routinely sheds chunks of concrete, like so much dandruff, into the river below. Engineering assessments have found that everything from steel corrosion to earthquakes to maritime accidents could cause major, perhaps catastrophic, damage to the span. Last July, one of Governor Cuomo’s top aides referred to the Tappan Zee as the “hold-your-breath bridge.”

After years of dithering, stopgap maintenance, and $88 million worth of studies, Cuomo fast-tracked plans to replace the bridge shortly after taking office in 2011. In December, state officials selected a design for a proposed new, $3.1 billion span. Construction, scheduled to begin this year, could be completed as soon as 2017.

The last hurdle to clear is financing. Last year, an analysis by a group co-chaired by Richard Ravitch and Paul Volcker questioned whether the Thruway Authority was creditworthy enough to fund the project, budgeted at the time to cost $5 billion. But then the winning $3.1 billion bid came in. State officials say they are confident they can cover that amount by securing a federal highway loan from the Obama administration and raising enough state funds, presumably from bonds backed by increased tolls (last week, they approved an initial $500 million issue). LePatner, for his part, questions the adjusted price tag. “Those of us who know,” he says, “know you can’t do it for $3 billion.” But state officials say they have built an appropriate cushion into the budget, and note that they are protected by a new state law that shifts financial responsibility for cost overruns to the builder.

As for the old bridge, “People need to know it’s not dangerous,” says Dan Weiller, spokesman for the Thruway Authority, “though the traffic conditions can be unsafe.” LePatner is unswayed—he’ll no longer cross it. “This is as vulnerable a bridge as you can get,” he says. “It could fall at a moment’s notice.”

What follows is a breakdown of how the bridge was built—and how it’s been falling apart since.

1. A Bridge Too Far

Improbably enough, the three-mile Tappan Zee, the state’s longest bridge, spans the Hudson River at one of its widest points. Governor Thomas Dewey proposed the site during his 1950 reelection bid. The Port Authority wanted to build a toll bridge at a narrower (read: cheaper and less complicated) juncture a few miles south; Dewey’s location had the advantage of sitting just beyond the Port Authority’s jurisdiction.

2. Cheap and Easy

Completed in just five years for a relatively inexpensive $81 million, the Tappan Zee “was one of the last bridges to arise out of a vanished American way of doing things: build stuff first, ask questions later,” wrote the Manhattan Institute’s Nicole Gelinas in a 2011 City Journal essay. Gelinas says the designers built “thin and light,” using an “untested design that ‘floated’ above bedrock,” which, inconveniently, lay beneath hundreds of feet of silt, sand, and clay. Among other things, the novel technique involved using foundational elements called buoyant caissons to anchor the main span in the soft soil, yielding substantial savings but a less durable structure.

3. And Ugly, Too

The bridge’s design married a towering cantilevered truss, offering sufficient clearance for ships navigating the deep channel on the east side of the river, to a squat causeway, which crossed shallow waters to the west. One of its engineers called the result “one of the ugliest bridges in the East.”

4. Earthquakes!

At the time the Tappan Zee was built, engineers didn’t seriously consider seismic risk, but researchers have since determined the bridge sits atop an active fault line. Over 100 years, a typical bridge’s life span, experts put the chances of a damaging earthquake at about 20 percent, and of a catastrophic one at around 4 percent. Its buoyant foundation is built to withstand vertical—not horizontal—forces, and a quake’s power would be magnified by a factor of four to six times by the soft riverbed. That the Tappan Zee’s design places the majority of its mass in its foundation, not in its superstructure, would further magnify an earthquake’s effects.

5. Worms!!

Marine organisms known as shipworms—actually a type of clam that can bore into submerged wood—weren’t a problem in the Hudson at the time the Tappan Zee was built, but after decades of anti-pollution efforts, they have returned. While authorities say shipworms haven’t feasted on the bridge’s timber pilings yet, a state report noted that they were “anticipated.”

6. Punch-Throughs!!!

More than 50 million vehicles traversed the Tappan Zee in 2010, up from 10 million in 1960, and while the bridge was designed to carry the 36-ton trucks of the fifties, it must now withstand today’s 45-ton behemoths. Thus the deteriorating concrete, which falls off the bridge in chunks, sometimes creating holes in the roadway through which the river below can be seen. Forty-five such “punch-throughs” were recorded in the eighteen months prior to a 2009 engineering assessment of the bridge, which estimated that nearly 60 percent of the deck needed to be replaced. The state has spent $750 million over the past decade on maintenance and estimates it would cost around $100 million a year to keep it operating in the absence of a replacement.

7. Strong As Steel (Which Turns Out to Be Not That Strong)

Steel, like concrete, is vulnerable to the corrosive effects of rainwater, especially when it mixes with road salt used to melt snow. The 2009 engineering assessment found that the Tappan Zee’s rate of deterioration is “unusually high.” The bridge’s drainage system was designed to dump water onto the substructure below the highway, causing major corrosion in crucial components like its “stringers,” horizontal beams that hold up the deck, and joints. Replacement deck joints manage to last only about ten years. Particular concern surrounds the stringers along the causeway section, which the assessment identified as “high risk.” Major cracking has also been observed on the causeway’s outer columns, reappearing soon after repairs.

8. Crash

Traffic accidents occur on the bridge and its approaches at double the rate of the rest of the New York State Thruway. Its seven lanes are narrower than today’s recommended average, and it has no shoulders, meaning that even fender benders can paralyze traffic.

9. Bridge, Ho!

Another potential threat is a maritime accident. In 2006, the Journal News reported that the state had acted to shore up the towers that hold up the main span after a study found that they could be brought down by a collision with one of today’s larger ships. Despite the retrofit, the 2009 assessment found that any rehabilitation of the bridge should include impact protection around the buoyant caissons.

10. Failure Is an Option

State transportation officials insist the Tappan Zee is still structurally sound. At least some experts disagree. Like other bridges of its vintage, the Tappan Zee has a “fracture critical” design. Because of a lack of engineering redundancies, it could conceivably be brought down by the failure of a key single component. A 2006 state report found that the bridge was “vulnerable to local or major collapse from a number of different causes,” saying that the most serious risks—though still remote—were posed by overload and the failure of steel parts.

11. The Chopsticks Solution

In December, a selection committee that included Richard Meier and Jeff Koons recommended a design for the new Tappan Zee. The winning bid came from a consortium of companies that handled the complex—and notoriously overbudget and behind schedule—$6 billion replacement of San Francisco’s Bay Bridge. The design consists of two parallel roadways, with the main span supported by cables strung from eight columns that jut distinctly outward, like chopsticks. Though the cheapest of three finalists, at $3.1 billion, the bridge will still be one of the largest infrastructure projects in New York State. In response to complaints from transit advocates, state officials say the bridge will be built with the capacity to add light rail or bus lanes—features cut from the project for now because of the additional cost. The new bridge, state officials say, is designed to last 100 years before it needs major repairs.