Late on the night of December 15, 2010, Trevell Coleman stepped out of the subway station at East 116th Street. The evening was bitterly cold, down to almost 20 degrees. He wore a North Face parka and a scarf wrapped around his head like a hoodie. He’d told nobody where he was going—not his mother, not his friends, not his relatives—because he knew they’d try to stop him.

With his hands jammed into his pockets, he began walking up Lexington Avenue toward East 119th Street. For years, he had been contending with flashbacks, nightmares, and intense feelings of guilt. The only way to stop them, he now thought, would be to talk to the police. And at this point, what did he have to lose? He was 36 years old and had almost nothing—no job, no money, and no apartment of his own.

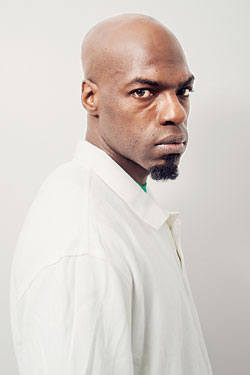

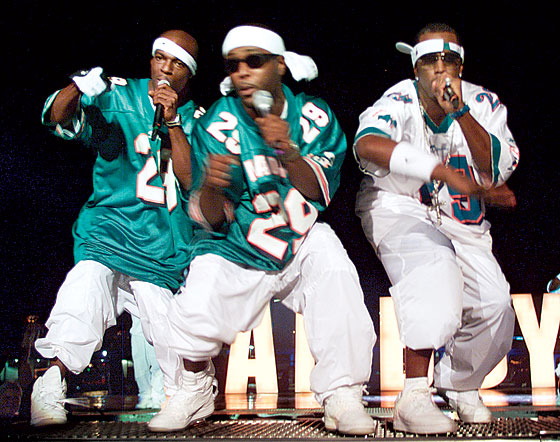

All he really had was a rap moniker—“G. Dep”—left over from his days as a member of Puff Daddy’s Bad Boy crew. Earlier that night, he had been playing the role of G. Dep once again, taping a public-access TV show in the back seat of a car. It was a far cry from 2001, when he’d been in regular rotation on MTV with “Let’s Get It,” the video that turned the Harlem Shake into a dance craze.

But now none of that seemed important. All that did matter was what he’d done half a lifetime ago, in the fall of 1993, when he approached a man late one night, fired a gun, then fled. He never knew where the bullets landed or what became of the man. And after seventeen years, he decided he needed to find out exactly what he’d done.

Coleman had already visited the 25th Precinct once before, not long ago. He’d spoken to a detective and given his cell number, but didn’t hear back. As a police source would later explain to a reporter, Coleman had been “high as a kite.”

Tonight, he was more clearheaded and had decided this was going to be his last trip to the precinct. If he didn’t get any answers this time, he would take that as a sign that he should move on and leave the past behind. But there was a chance, he knew, that once he started talking to the police, they might not let him leave. In fact, he might not get to walk the streets of East Harlem again for a very long time.

Shortly before 11 p.m., he opened the door to the 25th Precinct and stepped inside.

In early 1993, Trevell Coleman was an 18-year-old freshman enrolled at Iona College in New Rochelle. He’d made it through one semester, but soon after the second started, he decided he’d had enough. He called his mother and told her the news: “I’m leaving school because I want to be a rapper.”

“A what? A rapper?” she said. “Are you kidding me?”

She had hoped he might become a lawyer—he’d had an internship at a law firm when he was in high school—but she also knew he loved music. For years, she had listened to him rhyming in the shower, and she’d watched the composition notebooks pile up in his bedroom, each page filled with lyrics. But who quit college to be a rapper?

If he stopped going to school, she told him, she would stop supporting him: “You’re on your own.”

His mother had been 18 when she gave birth to Coleman, and she’d raised him by herself in the Bronx and Washington Heights. Eventually, she married a cop, got a job with the MTA, and bought a house in Piscataway, New Jersey. At first, Coleman had commuted from there to his Catholic high school, La Salle Academy, on the Lower East Side. Soon, however, he tired of the 90-minute trip twice a day.

He announced he wanted to stay with his grandmother, who lived in the James Weldon Johnson Houses in East Harlem. His mother wasn’t happy about the idea—she’d grown up in this housing project in the sixties and early seventies, during the heroin epidemic, and fled as soon as she got out of high school—but she agreed to let him move in with her mother. She didn’t know it then, but her son had already discovered an easy way to earn extra money, having hung out at the Johnson Houses from an early age: sell a package of crack and make $30.

After he quit Iona, he moved back in with his grandmother at 1840 Lexington Avenue, where his 14-year-old cousin Boysie also lived. To support himself, Coleman would stand outside on Lexington, on the sidewalk in front of his grandmother’s building, selling cocaine. On a good day, he made $200; other days his income covered little more than pizza and marijuana. Whenever he saved enough money, he and a friend would go to the Bronx and spend four or five hours at a recording studio.

“He was always good at what he did,” Boysie recalls. “Like playing basketball, rapping. He used to get everybody’s attention over that. And when people wanted to go out, they’d always ask him to go out, because he knew how to get all the girls.”

About six months after moving back to East Harlem, Coleman bought a .40-caliber handgun from a neighborhood dealer for $500. Among his peers who hustled on Lexington, it was an unspoken code: “If you had enough money to buy one, you ought to have one, in case anything happens.” And for a teenager who was only five-eight and 165 pounds, owning a gun seemed an easy way to appear more intimidating.

Coleman decided to use his new gun to make some extra money on the night of October 18, 1993, a month before his 19th birthday. He had never tried to stick up anyone before, but, he figured, it couldn’t be that difficult. He slid the pistol into the waistband of his jeans, climbed onto his bike, and pedaled through the Johnson Houses.

Just after 1 a.m., he spied a man in his thirties, standing alone beneath the elevated train tracks at Park and 114th, smoking a cigarette. Coleman leaned his bike against a car, strode across the avenue, and pulled out his gun.

“Where’s the money at?” he asked, pointing his pistol at the man’s torso.

The man didn’t respond.

“Where’s the money at?”

The man stepped toward him, caught Coleman’s eye, and grabbed for the gun. Startled, Coleman squeezed off three shots. The man winced, but didn’t make a sound.

Coleman darted back to where he’d left his bike, threw one leg over it, and started pedaling as fast as he could. He felt the man behind him, trying to grab him, and when he turned to look, he saw him stumble. Coleman didn’t look back again and instead sped north on Park Avenue.

He made a loop—right on 115th Street, right on Lexington, right on 112th—and then stopped at the corner of Park and 112th to peek back at the spot where he’d just fired his gun. There was a car parked in the wrong direction, pointing south on the northbound side of the street, headlights facing him. And he thought he saw somebody kneeling over a body on the ground.

Before anyone could spot him, he leapt back onto his bicycle and raced home. His grandmother was already asleep when he snuck inside. After stashing the gun in a dresser drawer, he collapsed on his bed still wearing his street clothes, his face pressed into his pillow.

Over and over, he replayed the shooting in his head: his finger pulling the trigger, the three gunshots, the man starting to fall. And each time he hoped for a different ending, one where he looked up Park Avenue and saw nothing—no car parked in the wrong direction, no body on the ground. Perhaps it had all been just a very bad dream, he told himself. The thought comforted him, and he clung to it, turning it over in his mind.

Coleman didn’t tell anyone what he had done and kept to his routine in the following days. He hustled on Lexington Avenue, hung out with friends, smoked marijuana—all while secretly terrified about the possibility that the police might catch him. At one point, when he was walking up Lexington, he saw two detectives in front of his grandmother’s building. It looked as if they had just been talking to a small group of people and were now getting into their car. But as Coleman got close, one of the officers popped back out.

“Do you know anything about a shooting?” he asked. His question felt routine, as if he had just asked a hundred other people the same thing. “No,” Coleman said, trying to act nonchalant. “I don’t know anything.”

As he walked away, he repeated the officer’s words to himself, parsing them for clues. They had said “shooting”—they didn’t say homicide. Maybe the guy was okay after all.

A week after the shooting, Coleman retrieved the gun from his dresser, placed it in a shopping bag, walked the four blocks to the edge of Manhattan, and tossed it in the East River. “That was the only way I knew how to handle it,” he later explained. “I just tried to get rid of the memory of it, of the whole thing.” But every time he passed 114th and Park, he still found himself reliving that night: the sound of his gun going off, the man wincing and stumbling. He began avoiding Park Avenue altogether.

Ten days after the shooting, the police arrested Coleman for selling crack. Finding himself in Central Booking, he was consumed by one thought: Are they going to come in here any minute and say ‘We got you’? But the police knew nothing. The courts treated the 18-year-old as a “youthful offender”; he got off with no state prison time, and his case was sealed.

One year passed, then two, and the cops never arrested him for the shooting. “They didn’t come yet,” he’d repeat to himself like a mantra. “Maybe nothing happened. Nah. Nothing happened. Nothing happened.” His efforts to convince himself the shooting hadn’t even taken place fell short. “At the back of my mind,” he says, “I knew something happened.”

His mother didn’t know what was going on, but she had begun to observe changes in his behavior. He had always been soft-spoken, but now he was quieter, more introverted. “He stopped smiling,” she says. “I couldn’t understand why he was so serious.” Others, however, didn’t notice a thing. “He seemed to be the same kind of kid I knew as a child,” says his uncle Clarence Coleman. “He didn’t look like he was haunted by anything.”

In 1996, he was arrested three times in two months for selling cocaine. His punishment: seven months in state prison. He was 22 when he got out. He had already become known in New York’s underground rap scene; Gang Starr gave him a shout-out in the liner notes to their 1994 album Hard to Earn. If he didn’t want to spend the rest of his twenties in a prison cell somewhere upstate, he decided, now was the time to get more serious about his music.

In the autumn of 1998, Coleman found himself standing on the corner of Lexington and 112th Street one night when a silver car rolled down the avenue, its blue halogen headlights drawing everyone’s attention. The driver pulled up to the curb and cracked his window.

“Dep, right?” he said. “Get in the car.”

It didn’t take long before everyone in the Johnson Houses had heard the news: Puff Daddy had sent a Bentley to fetch Coleman. Recently, Black Rob, a Bad Boy rapper from the Jefferson Houses next door, had invited Coleman to appear on an album. After hearing Coleman in the recording studio, a Bad Boy senior executive had pulled him aside and asked if he wanted to sign a recording contract.

Bad Boy Entertainment released G. Dep’s first album, Child of the Ghetto, in the fall of 2001. Vibe gave the album four and a half discs and profiled him in a feature called “People on the Verge.” By then, Coleman was 27 and had a 3-year-old daughter. With his daughter and her mother, he moved to a townhouse in Scotch Plains, New Jersey.

He had told nobody about the shooting, but even after he’d left East Harlem, there were moments when memories of what he’d done would bubble up. He would be at the movies, a tub of popcorn on his lap, watching the screen, when one character would pull out a pistol and shoot somebody—and suddenly he was right back in 1993, on Park and 114th. When he was younger, he’d identify with the perpetrator on the screen—“I shot someone, too,” he’d say to himself—but as he got older, he found himself empathizing with the victim. In the middle of the movie, he’d start wondering if the man he had shot at was still alive—and then he’d question whether he even deserved to be in a theater at all, rather than in prison. The lights would go back on, everyone would file out, and he’d leave with no memory of the movie he’d just seen.

Then there were the nights when he’d stay out late, working or partying until 2 a.m., coming in after everyone else was asleep. Sprawled on the sofa in the living room, exhausted and high, he’d find himself obsessing yet again about the shooting. His paranoia about the cops catching him had almost disappeared, but on nights like this he felt overwhelmed by an intense fear. “Like my soul is going to burn in hell—that fear,” he says.

He had been smoking marijuana since the eleventh grade, but after he signed with Bad Boy, he tried a “dust blunt” for the first time—marijuana mixed with angel dust—and found that PCP helped alleviate his torment in a way that marijuana never had. “It was really at a point where I used to hear voices, and my conscience used to tell me: ‘What you did was wrong,’ ” he says. “That was really the only drug that made me not think about anything.” Before too long, he was smoking so many dust blunts that the executives at Bad Boy took notice.

He’d signed a $350,000 contract with Bad Boy four years earlier, but by the end of 2002, he was broke. After he lost his lease on the townhouse in New Jersey, he packed the family’s belongings and drove to the Johnson Houses. “Now I’m bringing the U-Haul right back up to 1840,” he says. “It was depressing.” Not only had his career stalled, but he was living, once again, just a block away from the scene of his crime.

Not long after moving back to East Harlem, Coleman lost his grandmother—and his deal with Bad Boy. To cope, he began smoking more PCP. The more he smoked, the more his rap sheet grew. Between 2003 and 2007, he was arrested seventeen times, mostly for drug possession, sometimes for trespassing (hanging out in a building that wasn’t his, often to get high), and once for “theft of services” (slipping through the exit gate to steal a free ride on the subway). Between trips to Rikers he tried to jump-start his career, without much success.

“Everything fell apart,” says Boysie Coleman. “He started using more. Everything changed about him. He wasn’t the person I grew up with. He wasn’t talkative. He was zoned out.” His aunt Cecelia Coleman recalls, “He was always preoccupied. He wasn’t socializing the way you would normally do. Half the time he wouldn’t even say anything. You’d say, ‘How are you doing, Trevell?’ And he’d say, ‘I’m okay.’ And that was it.”

By now, Coleman was married and had two more kids: twin boys. He’d met his future wife, a former airline worker named Crystal Sutton, at a nightclub and married her in 2004. His addiction to angel dust made for a tumultuous relationship. She would enroll him in rehab programs, but he never stayed long. And she could always tell when he’d just been smoking: He would stutter, his whole body would shake, and his stench would remind her of formaldehyde.

Several years after they got married, he told her that he’d fired a gun at a stranger when he was a teenager. “One time he said he shot someone and they lived,” she says. Another time, it was a slightly different story: “He shot someone, and he doesn’t know what happened to them.” She wasn’t sure what to think. Once, while he was high, he’d announced he was Jesus. He’d also accused her of being a cop. At least three times, he’d been carted off to hospital psych wards.

Coleman confided his secret to three other people, too: his mother, his daughter’s mother, and a friend. He recalls that his mother responded by saying: “Well, that was a long time ago, that was in the past.” And then she’d change the subject. “I don’t think she really believed me,” he says. “She was just bringing up other stuff: ‘Are you still going to the rehab?’ She didn’t really want to talk about it.”

Coleman would sometimes mention that he was thinking of going to the police. “I would bring it up just so people would be like: ‘Man, you can’t be serious. Don’t ever do that.’ And I’d be like: ‘You know, you’re right,’ ” he says. He was hoping somebody would make a convincing argument for moving on. “I just wanted somebody to say, ‘Don’t worry about it,’ ” he says. But after a while, he found that no matter whom he told—or what they said—nothing could quiet his conscience. “There wasn’t really an answer I could get. I was looking for something that wasn’t there.”

In the spring of 2010, Coleman found himself lying in a hospital bed with a fractured skull, stitches in his head, a bandage over one eye—and no idea how he got there. The last thing he remembered was smoking PCP and wandering onto East 115th Street. He thought that he’d been hit by a car, but he didn’t know for sure. “You could’ve died,” his mother told him, “and I’m not going to lose you like this.”

He entered a 30-day rehab program in June 2010 and spent hour after hour sitting in groups, listening to other addicts share their mistakes and regrets. “A lot of people were really cleansing their souls and really getting to the root of their problems,” he says. “I was not. I would just be embellishing, telling stories about getting high. I wasn’t being totally honest.”

After finishing the program, he signed up for more outpatient treatment at a hospital in the Bronx. He was trying harder to stay clean than he’d ever tried before, but there were still slip-ups. On August 2, a cop snapped a pair of cuffs on him after finding him smoking PCP in the Johnson Houses, inside a stairwell at 1591 Park Avenue. On November 17, another cop caught him in the same building with PCP.

It was no coincidence he kept getting arrested inside 1591 Park. The building overlooks the spot where he fired his gun back in 1993, and for reasons he couldn’t quite explain, it had become a favorite place to get high. He’d light up in the stairwell and stare out the window at the Metro-North tracks above Park Avenue. “Maybe that was my way of confronting that demon. Or maybe I was just becoming that demon. Or that demon was consuming me,” he says. “That’s how crazy I was getting.”

At times, his life felt like a series of endless internal calculations, all part of an effort to, as he later explained, “balance myself out.” If he bought a coat, he might scribble on one pocket with a marker before putting it on, just to deprive himself of the chance to wear something completely new. He never had much money, and he was so determined to give away what he did have that a few times he stuffed bills into the coin slots of pay phones, then walked away. Afterward, he’d feel a little better—“I did think, Well, okay, now I don’t have to feel like I have too much regret,” he says—but the relief was only temporary.

Coleman and his wife had separated, but he still stopped by to visit his 7-year-old sons. Some days, he’d be seated with them at the table, sharing a meal, thinking how blessed he was to have such beautiful boys, and suddenly be seized by guilt. Did the man he shot at have any kids? What happened to them? And why should he get to spend time with his kids if there was a chance he’d robbed another child of his father?

Soon after Coleman walked into the 25th Precinct on that freezing night near the end of 2010, he found himself in the back of a police car, riding through East Harlem. At the 25th Precinct, he’d admitted to a detective the basic details of his crime: the location, type of gun used, description of victim. Once the detective heard the crime’s location, he called over to the precinct that covers that area.

By 12:30 a.m., Coleman was seated inside an interview room at the 23rd Precinct, surrounded by cinder-block walls. A detective asked him questions about what had occurred, then wrote down his answers, creating a narrative of what he said he had done. The last line of his confession: “The reason I turned myself in was because I felt awful about what I did and I wanted to make it right for this guy’s family.”

What Coleman didn’t know was that before he’d walked into this room, the detective had searched the precinct’s homicide log book and found what looked like a match: John Henkel, white, 32 years old, shot on northbound side of Park by 114th, “possible .40 caliber shell case.”

Only after Coleman signed his confession did he get an answer to the question that had been haunting him for seventeen years: “I just wanted to tell you that the guy died.”

In the hip-hop press, G. Dep’s confession became huge news. Had he really gone to the police and snitched on himself? Online commenters weighed in: “G-Dep is an idiot.” “Nobody does that-EVER.” “What a dumb ass!” When Coleman’s family heard what he had done, they persuaded Anthony Ricco, one of the city’s top defense attorneys, to represent him. They hoped that the district attorney would let Coleman plead guilty in exchange for a reduced sentence.

That didn’t happen, and last spring, the case went to trial. Ricco tried to convince jurors that although Coleman confessed to a shooting, the police had matched his words to the wrong cold case. He teased out numerous discrepancies between Coleman’s confession and the Henkel murder—color of the victim’s hair, color of his jacket, time of year the murder occurred—but the jury didn’t buy it. In the end, it was Coleman’s own words—not only the written confession, but a videotaped confession he gave afterward—that got him convicted of second-degree murder.

An autopsy of John Henkel’s body revealed he’d been shot three times: in the chest, abdomen, and back. His brother identified his body, which featured a tattoo of the word love written vertically on his left forearm. The night he was shot, he was carrying a billy club. His wallet held only two bills: a $5 and a $1. A toxicology report later showed he had PCP in his system.

Henkel lived in Ridgewood, Queens. Why was he in East Harlem at 1 a.m.? “It’s logical to assume he was there for some drug-related purchase or to use drugs in some manner,” the prosecutor told jurors. Nobody from Henkel’s family testified, and there was no mention of any wife or kids left behind.

When a New York Post reporter tracked down his stepbrother Robert Henkel upstate to get his reaction to Coleman’s confession, Henkel said: “I think he’s an idiot … He has three kids and a wife. It was years and years and years ago. Finally, we’re not always thinking about it … and now it has to be dug up all again … After all this time, yes, he just should have shut up.” When asked to comment about Coleman for this story, Henkel said, “He can go fuck himself. Okay? Good-bye.”

The jury’s decision to convict Coleman pushed both his wife and his mother to tears. But when Coleman returned to Rikers and got on the telephone, nobody could believe how he sounded. “He’s like, ‘Hey, how you doing, man?’ ” says Jonathan “Kwame” Owusu, who was his manager. “He was upbeat. It didn’t make any sense.”

Three weeks later, a judge sentenced him to fifteen years to life. “I was happy,” Coleman recalls. “It sounds crazy to say you were happy about getting a fifteen-to-life sentence, but I was. It just seemed to me like the end of a nightmare … I was living in 1993 for seventeen years.”

Today, Trevell Coleman is prisoner No. 12-A-2293 at Elmira Correctional Facility, a maximum-security prison some 240 miles from East Harlem. Now 38, he won’t be eligible for parole until soon after his 51st birthday, near the end of 2025. And even then, there is no guarantee that the parole board will release him.

One morning in August, he sits in a prison visiting room wearing his usual attire: forest-green sweatshirt, matching green pants a size too big, white canvas sneakers. Rosary beads and a cross dangle from his neck, tucked inside his sweatshirt. A few white hairs dot his black goatee.

It has been four months since his trial ended, and while he no longer seems buoyant, he insists he has no regrets. “I don’t know how me being incarcerated—I can’t measure how much it makes anything any better,” he says. “But I just know what I had to do.”

While on Rikers awaiting trial, he wrote a memoir—300-plus pages, handwritten—almost all of it in rhyme. Writing comes more easily to him these days, he says, since he’s no longer high all the time—and no longer preoccupied with the past. “It wasn’t something I was going through periodically; it was something that was like a knot at all times,” he says, curling one hand into a fist. “Sometimes I didn’t even want to walk with my head up. I just wanted to look down. If I stood up, I felt funny, like, ‘Who am I to be looking up?’ ”

From the time he was a child, Coleman would always tell his mother, “I love you, Ma.” She never doubted his sincerity, but for the past nineteen years he barely ever looked at her when he said these words, instead casting his eyes down and uttering the sentence as if it were a question. On September 15, his mother and wife drove up to Elmira to see him. They sat together at a table in the visiting room, and when he said, “I love you, Ma,” he held his head up and looked her straight in the eye.