|

A bodega pit stop.

(Photo: Edward Keating) |

It was through the clinic that Carlos was introduced to the Saturday soccer game. (The team is part of South Bronx United, an organization that runs a soccer and tutoring program.) His case manager, 24-year-old Elvis Garcia Callejas who himself came to the country as an undocumented minor moonlights as co-coach of the team. Most of the boys playing for him also arrived on their own from Central America and have, like Carlos, been temporarily released to family members in New York. They are, however, in removal proceedings, which means they face deportation. (Because of their legal limbo, I am identifying them by their first names or nicknames.)

They are well aware of the precariousness of their situation. On the sidelines, the boys reel off the dates they will appear in court to determine whether they can in fact stay the way pregnant women recite their due date. Being among other teenagers who are also facing possible deportation seems to have forged a tight bond among the players. They throw their arms around each other’s shoulders, affectionately calling each other loco. Some of the boys’ relationships predate Saturday soccer. Ariel and Jose both 17-year-olds from Honduras met when they were waiting in line to be seen by a nurse at an Arlington, Texas, adult detention facility, which they refer to as a hielera, or the icebox, because of its very cold temperature. After being transferred to a shelter for juveniles, they were flown to LaGuardia Airport, where they were released to their mothers, whom they’ve lived apart from for a decade.

Ariel tells how their parents reacted to seeing the sons they’d left behind as small children. Jose’s mother was on the phone when the boys emerged; she threw it to the ground and started screaming. Ariel’s own mother grabbed onto him and wouldn’t let him go. Even when I couldn’t breathe, he says, smiling.

|

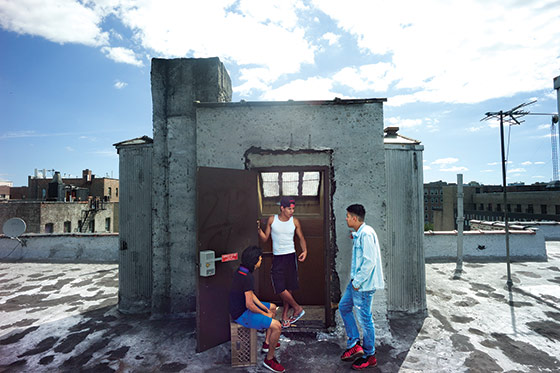

Carlos, center, with friends on the roof of his building.

(Photo: Edward Keating) |

Living together is an adjustment. For most of their childhoods, the boys didn’t know the women who now serve as their caretakers. That’s particularly true for Carlos and his grandmother, whom I’ll call Alicia. She’s lived in the United States for almost 30 years and visited Honduras just a handful of times while Carlos was growing up. After losing her house-cleaning job three years ago, she has since supported herself by selling empanadas and juice on the street, a few blocks from the Grand Concourse in the Bronx, not far from the apartment she shares with Carlos.

In Honduras, Carlos started doing odd jobs at 11, and as a teenager, he washed dishes and bussed tables at a restaurant 60 hours a week. But while he awaits court hearings in October that will determine whether he can stay in the United States, Carlos is not permitted to seek legal employment. Even people with papers can’t find work, he says to me. I’ve seen people with green cards cry because they can’t find a job.

Since June, when he earned his GED, Carlos’s days have acquired an unstructured quality. He listens to bachata and reggaeton. He misses his ex, Maria, a 16-year-old Puerto Rican girl who broke up with him a few months ago. Sometimes Alicia will send him to deliver empanadas. He high-fives the other vendors on the Grand Concourse, smiles a greeting at the owner of a coffee shop. I know everyone, he boasts. He soaks in the attention.

It’s the same on the field. At the Saturday pickup game, the boys don’t have assigned positions; they either serve as goalie or try to score. While some players love to play defense, Carlos likes to attack. When he scores a goal, he grinds his hips and turns in a circle as his teammates laugh.

|

At soccer with his coach, Elvis Garcia Callejas.

(Photo: Edward Keating) |

Carlos’s grandmother Alicia constructed her empanada food stand by herself. The oversize umbrella patched with duct tape came from Home Depot. She wheels it in a metal shopping cart along with a vat of frying oil, the wooden card table she stacks with lemonade and tamarind juice, and the uncooked empanadas she makes at home and sells for $1.50 each. On an unseasonably cool August afternoon when Carlos and I visit, business has been light. Alicia doesn’t expect to earn more than $40 for the day.

She plunges a cheese empanada in the oil, and before turning it with a pair of tongs, removes a ticket from her jeans’ pocket. She’s been fined $2,000 for violating the New York City health code. She says she will just tell the judge she can’t pay it. With her rudimentary English and third-grade education, this is the only way Alicia can envision earning a living. She has to pay rent and ConEd, and feed Carlos and herself.

Subscribe

Subscribe

The Age of the Auteur in Streaming TV

The Age of the Auteur in Streaming TV

The Approval Matrix

The Approval Matrix David Edelstein on This Is Where I Leave You

David Edelstein on This Is Where I Leave You

A Very Different Kind of Sexual Revolution on Campus

A Very Different Kind of Sexual Revolution on Campus

Derek Jeter, in Private

Derek Jeter, in Private