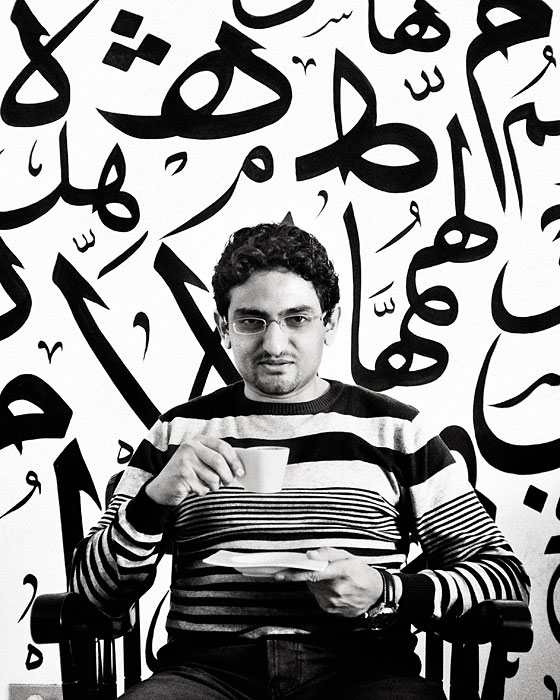

CAIRO, Egypt — It has now been twelve months since Wael Ghonim—a studious, physically small, prosperous computer engineer living in Dubai and working for Google—became in the public’s mind the symbol of the Egyptian revolution. If before the protests began you had scoured all of Egypt, pharaohlike, for candidates for this position, no one would have suggested Ghonim. He was a political naïf who lived mostly as an expatriate in Dubai; he had few connections and no obvious charisma. “A real-life introvert and a virtual extrovert,” one of his closest friends told me. “A real computer geek.”

But the revolution, at first, was itself more extroverted online than in the streets. And though the protests had many authors, and a long prologue, Ghonim was its best propagandist, and it was Ghonim perhaps more than anyone who figured out how to sell the promise of revolution to ordinary Egyptians. He organized many of them online and, in so doing, helped radicalize them. Hosni Mubarak had ruled Egypt for 30 years, and the campaign to oust him had spent a decade in an activist niche. In a few short months last year, it became a mass movement.

Ghonim was from the outset his own cadre. One day in June 2010, his wife found him sobbing alone in his study in Dubai. On his Facebook wall, a friend had posted a brutal photograph of the body of a young Egyptian activist named Khaled Said, beaten to death by police—his jaw had been dislocated, his face so broken it was blue. Had Ghonim been more politically engaged, the photograph might not have carried so much surprise; human-rights groups and bloggers had been publishing evidence of state torture for years. Convinced the photograph had been doctored, Ghonim sent a frenzy of messages to a political e-mail list. But the photograph was authentic, and somehow this discovery permanently altered the way he thought about his homeland. Ghonim set up a Facebook page as an online vigil. He called it We Are All Khaled Said.

To Ghonim, who as a kid had spent his time so buried in bulletin boards that his father, a physician, took away the computer until his son could pay the dial-up bills himself, the Internet had always been a ham radio, a way of connecting. It took just one week for the Khaled Said Facebook page to gather its first 100,000 members, and Ghonim now had a community of outrage. The members of his page suggested public demonstrations, and throughout that fall Ghonim took their advice and helped them organize. He was cautious, though; he didn’t consider the Facebook page a political protest so much as a moral one. He was also worried that he would be discovered by the Egyptian authorities, and so did all he could to remain anonymous. (He used as his avatar the Guy Fawkes mask from V Is for Vendetta, a movie he loves.)

Early in January, the Tunisian dictator Zine el Abidine Ben Ali succumbed to protests there and fled to Saudi Arabia. Ghonim had been trying, without much success, to build enthusiasm for a big demonstration on National Police Day, later that month. Tunisia suggested to him the outside extreme of what was possible. On Facebook, he had at first advertised the protest, sarcastically, as “Celebrating Egyptian Police Day.” Now he switched it. “The Day of the Revolution Against Torture, Poverty, Corruption, and Unemployment.” He felt a rush. The invitation, posted and reported, eventually reached over a million people. On January 25, the protest began in Tahrir Square, its particulars having been planned by other, more experienced activists, and it has never completely left.

Two nights later, Ghonim was kidnapped by the police on the streets of Cairo. He spent eleven days in prison and became, unwittingly, one of the earliest liberation cries of the revolution. Released, he appeared on Egyptian television, weeping over those killed in the demonstrations, and then, delirious, in the square itself, wearing a rugby-style shirt with the oversize icon of a lion splayed across the left breast. On February 11, Hosni Mubarak abdicated the presidency.

What followed, for Egypt, has been a complicated kind of freedom. For Ghonim, it has been a complicated kind of fame. Because he is young and modern, because he works for Google, because he is secular and politically unattached, Ghonim came to represent the element of the Arab Spring that most seduced the West—the proof that crowds organized online could even bring down dictators. Suddenly, Ghonim was extraordinarily famous. In March, he sold the rights to a memoir to Houghton Mifflin Harcourt for a startling $2.25 million, and he soon took a leave from Google. (The book, Revolution 2.0, is out this month.) In April, he was flown to New York, where Time named him one of the world’s 100 most influential people. Last fall, he had the disorienting experience of being nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

But in Egypt, Ghonim’s liberal optimism was a temporary bridge between a small core of activists committed to radical change and the far larger number of Egyptians who are much more cautious. This bridge has all but collapsed. The newly elected Parliament will be dominated by Islamists, and the military’s campaign of repression has deepened. The Nobel laureate Mohamed ElBaradei, the great liberal hope, announced last week that he was withdrawing from the race for president. When he goes out in Cairo, Ghonim is often confronted both by opponents of the revolution, who hold him responsible for its radicalization, and by more doctrinaire revolutionary activists, who believe he never really shared their views at all. One activist opened a mocking Twitter account under the handle @GhonimWithBalls. A young comedian, Ahmad Spider, made himself famous by unspooling a conspiracy theory in which Ghonim is the agent of a global plot, run by Freemasons, to destroy Egypt. To many Egyptians, Ghonim had almost seemed to materialize from the Internet and then disappear back into it. “Wael Ghonim,” one Egyptian journalist said, searching her memory, when I explained why I was visiting Cairo. “What is he even doing these days?”

Since the spring, Ghonim has come to view his reputations abroad and in Egypt as if they are operating inversely, on either end of a seesaw, and he monitors them, ambivalently, all the time. In Cairo last month, ABC News wanted to film him voting, but he agreed to cooperate only if the producers would arrive at the polls independently and then pretend to come upon him by accident. (ABC News declined.) Houghton Mifflin Harcourt had planned a broad international publicity campaign for his book, but Ghonim abruptly pulled out of the first leg, saying he’d prefer to celebrate the anniversary of the revolution in Egypt. When his fame builds abroad, “it kind of backlashes on me here,” he says. “And I don’t like that.”

A little more than two weeks ago, Ghonim settled into his regular three-hour flight from Dubai to Cairo. His seatmate, an older Egyptian executive type, recognized him immediately and started right in. “Isn’t enough enough?” the man asked. “What are you doing to this country?” The executive turned out to be an engineering consultant whom Ghonim pegged at around 50; he might have been Ghonim himself born twenty years earlier. Ghonim is both an interested listener and not great at getting out of conversations, and so he spent the flight absorbing his seatmate’s story: The older man had supported the protests at Tahrir Square and experienced “the epitome of happiness” when Mubarak had been forced down on February 11. But as the revolution had barreled on, some of its demands seemingly extreme, and the country continued to falter, the consultant had come to resent all of it. Recently he had even joined the counterprotests denouncing the revolution that had materialized in Abassiya Square. As the two men argued, Ghonim began to feel that he shared his seatmate’s underlying sense of fear for the country’s future. The man was unsparing. He told Ghonim, “You’ve ruined Egypt.”

When Ghonim sat awake in jail, isolated and singing to himself for company, it was the passwords that preoccupied him. The passwords, he thought, would be a problem.

Ghonim had been kidnapped on day three of the revolution—tackled to the ground, stuffed in a car—just after leaving dinner with two of his Google colleagues in the posh neighborhood of Zamalek, and the police took his laptop. This was the first time Ghonim had flown to Cairo to physically participate in any protest he had helped organize, and now the risks of such engagement were very real. His e-mail, if properly dissected by the secret police, would yield a contact list for the revolution. His laptop wasn’t even powered off; it was just in sleep mode. The layers of protection were so thin. Ghonim’s hope, when he reasoned it through, was that it would take the police long enough to focus on his e-mail that his friends in Dubai would realize he was missing, guess he was being interrogated, and change the password. This seemed like too many conditions to count on.

Ghonim spent the next eleven days blindfolded. He was not beaten badly, but neither was he permitted to shower; over time he began to experience coughing fits, and a rash spread over his body. He had no idea what had happened to the revolution—whether it had toppled the regime, been violently put down, or simply evaporated. There were daily interrogations. Ghonim quickly confessed to being the administrator of the Khaled Said website and to having called for the January 25 protests; he gave up the password to the site itself, figuring the worst they could do was to shut the site down. When they asked for the password to his computer, he delayed, saying that it had been automatically reset and the new one was in his phone, which was at the time in some separate bureaucratic cubbyhole. Mostly, though, the interrogators were searching for the revolution’s source in the wrong place altogether, in Ghonim’s tenuous links to the powerful. What was ElBaradei’s role in the protest? What was the relationship between the CIA and Google? It took three days for the police to access his computer and register an interest in his e-mail. “I need the password,” one of his interrogators said finally. Ghonim weighed his options and state security’s reputation for torture. He gave it up. That night Ghonim was sleeping in his cell when his guard woke him. “Your e-mail password is not working,” his interrogator said.

The delay had been enough. A friend who worked at Google had gone to Ghonim’s villa in Dubai and used his iPad to change his e-mail password. (Ghonim’s wife did not know the password to his tablet, but his 8-year-old daughter, Isra, did: She used it to play Angry Birds.) After ten days, Ghonim’s guards told him that he would be freed. Prominent activists had demanded his release, and the interior minister acquiesced in hopes of demonstrating that the regime could be amenable to change.

Ghonim was permitted to call his wife, Ilka, in Dubai. His voice was so hoarse that she didn’t believe it was him. “What is my mother’s maiden name?” she asked cautiously. Then he was out.

It was February 7, day fourteen. The revolution had gone on without him; the protesters had stayed in the square, but neither side had buckled. Mubarak had just given a dramatic speech, volunteering to step down in September, and many of the young protesters were getting calls from their parents telling them to come home, that the revolution had run its course. Ghonim contacted a television host he knew, Mona al‑Shazly, and told her that he wanted to appear on the program that night, on an independent station called Dream TV.

It was immediately obvious to Ghonim’s friends that he was not well. Normally, Ghonim is as logical and straightforward as an algorithm. Now he was an emotional mess. “He was in total breakdown. We tried to calm him down,” says his friend Amr Salama, a young Egyptian filmmaker. “We started to test things—is that right to say or not? After he got on the air, he forgot it all.”

The camera settled on Ghonim, sitting across a round table from Shazly. His hands were clasped on the table, and he was staring down fixedly. He spoke without lifting his eyes. At first he stuck to the case he and his friends had designed for the revolution: He wasn’t a hero, because the heroes were those who had died in the streets. “There isn’t one of us here that is on some high horse leading the masses.” He took issue with how the state-run media had denigrated the protesters as paid-for tools of foreign agents. “We live in great homes, and we drive great cars,” he said. “I don’t need anything from anyone, and I never asked for anything from anyone.” Then Ghonim began to crack. “I’m not ungrateful, it’s just that it’s not right … it’s not right … that my dad, who has lost an eye … and could lose the other one any day … could spend twelve days without knowing where his son is.”

“Wael, catch your breath,” Shazly said. “This is not an interrogation.”

When they came back from commercial, Shazly asked if Ghonim had seen a series of photographs.

“No, I haven’t seen a single one.”

They were snapshots submitted by families of protesters who had been killed during the two weeks of the revolution. The camera fixed on each of them, a dozen young Egyptian men, nearly all of them smiling, in better times. By the third photograph, Ghonim put his head down and started to sob wildly. “I want to tell every mother and father who lost a son that it’s not our fault,” he said, half-regaining his composure. “I’m sorry, but it’s not our fault. It’s the fault of everyone who held on to power and clung to it.” He started to cry again, and his voice got high and pinched. “I want to leave,” he said.

In the studio’s lounge, Ghonim started to kick the furniture. “Animals!” he shouted. “Animals! Animals!”

When scholars discuss why, in its last few days, the revolution was reinvigorated, the main reason they give is the reaction to the brutal charge of the regime’s mounted thugs into the square on February 2: “the Battle of the Camel.” But Ghonim’s interview, they say, was one of the significant secondary events that helped nudge things along. “Wael Ghonim’s Dream TV appearance was kind of a turning point at this emotional level for the revolution. It forced people to make an emotional decision—which side am I on?” says Frances Hasso, a Middle East–studies scholar and sociologist at Duke. “There was a little bit of an Egyptian soap-opera quality to it. You could see that he wasn’t really radical.” Hasso was not in Egypt at the time, but she was talking about Ghonim’s appearance with an Egyptian academic friend in Cairo, Zeinab Abul-Magd. “She said, ‘I know it—tomorrow all the mothers will be out there with the strollers and the babies.’ And they were.”

Ghonim does not exactly prefer Dubai to Cairo. But he is a pragmatic person and has come to terms with its appeal: The schools are better, his wife likes it, and the cleanliness of life permits a certain focus. “There are not so many distractions—you can just innovate,” he told me. There may also be a deeper connection. Like him, the city is an amalgam of modern and traditional, of West and East. “People like Wael and myself kind of innately refuse the dichotomy of Arab or modern, of Islam or modern,” says his close friend Moez Masoud, a prominent thinker on contemporary Islam. “A lot of people in the West will see the jeans and the MacBook Air and think that Wael is heavily individualistic. I think it is more complex.”

Since Ghonim was an adolescent, raised in Saudi Arabia and Cairo, the Internet has been the object of his idealism, and the place where he feels himself most purely expressed. Ghonim was always excellent at school but less sure of himself socially—“never very capable of expressing emotions,” as he puts it—and as a teenager he discovered he preferred virtual interactions to those in the real world. One could be more forthright online, and even in person, Ghonim has the impulsive, withering energy of a message-board regular. “The Internet has been instrumental in shaping my experiences as well as my character,” he writes in his memoir. By the time he was an undergraduate at Cairo University, he had launched his first startup, a social-networking site called Islamway.com, where users posted religious sermons.

Ghonim came to the United States in June 2001 to study and stayed for six months. Here, the distance between the virtual world and the real one began to narrow. He met a young American woman, a Muslim convert, online, and after just a few weeks of knowing each other, they married. He was struck by the religious freedom American Muslims enjoyed, the quality of the universities, the openness of political expression. “We’re being fooled in Egypt!” he would tell his friends back home. But the culture also seemed lonelier, and he missed the communal bonds of Egyptian society. Ghonim’s preferences, he discovered, were rather conservative. Through his wife, he has been eligible for U.S. citizenship for a decade, but he has never applied. I asked him once if he thought Egyptian society, in the compress of globalization, would become more Western. “I hope it doesn’t,” he said fervently.

He told Google he wanted to change the Middle East: “I believe that the Internet is going to help make thathappen.”

But if America did not seem perfect, Google did. For a half-decade he applied for Middle East–based jobs that the company advertised. Ghonim “marveled at its culture, which was all about listening to others. Data and statistics ruled over opinions.” He was repeatedly rejected, but he got his M.B.A. in the meantime and worked for a succession of Middle Eastern technology companies. Finally, in 2008, Google hired him for a marketing position in its satellite office in Cairo. A year later he was promoted to Dubai to oversee marketing for the entire Middle East. In his initial interviews, Ghonim had been asked why he wanted to work for Google. He wanted to help change the Middle East, he said: “I believe that the Internet is going to help make that happen.”

Most places in the world that are educated, cosmopolitan, and alluring are also wealthy; they are the places you go to get jobs. The crazy accident of oil in the Middle East means this is not the case in Egypt. Cairo is easy to love—it is the educational center of the Islamic world and a casual, social city; men and women are out on the street, hanging out in restaurants at midnight. But since at least Ghonim’s father’s generation it has been an exporter of talent. Globalization has burdened Egypt with an Uncle Tom problem, where every success becomes a sellout. But it has also created a class of talented Egyptians whose success had not depended on the government. At the core of Ghonim’s anger at the regime, says his close friend Sherif Mamdouh, was the feeling that “the Egyptian people were always being underestimated by their own government. He was about showing what the Egyptian people could do.”

It had seemed to Ghonim, when he first started to build the Khaled Said page, as if the existing activist groups were barely even trying to broaden their appeal. To Ghonim, a political movement was in essence a marketing operation, and he treated it as such. His appeal would be emotional, rather than intellectual, and would engage the conviction that Egypt deserved something better. He kept his identity secret, and to create a sense of immediacy he often used the collective “we,” not the singular “I.” On the websites of more doctrinaire groups, he saw angry, alienating rhetoric: The police were often described as “dogs of the regime.” Assiduously, Ghonim scrubbed the comments on his page of similar language. He avoided, at first, any references to violence between the minority Christian and Muslim communities, for fear of inflaming sectarian tensions.

The language Ghonim prefers is Silicon Valley inflected, and consumerist; when he speaks about his role, he sometimes says that he “signaled” the crowd. Whenever Ghonim took a stand with his page or organized a demonstration, it was an amplification of an idea that had first been proposed by one of his readers, which Ghonim then made the subject of a poll: Majority ruled. Traditional protests had been held in front of government buildings with anti-regime signs. The Khaled Said protests took place along riverbanks, silent, the participants dressed in black. It was a theater of political self-expression, not anger. You did not have to have a political program in mind, or be willing to risk jail, or even to think of yourself as an activist in order to participate.

Identity operates in fragments, particularly online. What Ghonim understood is that if the circumstances were right, if the ethical appeal were precisely calibrated, a movement could capture a piece of everyone’s self-image, and it could have a far broader reach. There were many Egyptian revolutions, not all of which moved in coordination. But this was Ghonim’s: the mothers with strollers who, for a while, assumed the identity of revolutionaries and stepped out into the square. And who then, almost as quickly, shed it and moved away.

Tahrir Square is so enormous and so busy that if you approach it walking east, having crossed the Nile on the Qasr al Nil Bridge, it takes you a few minutes just to find the political demonstration at all. Tahrir Square is not just the symbolic center of the revolution but also a main transportation hub for a metropolis of 16 million people—it is the National Mall, but it is also Times Square. Today much of it is consumed by a massive construction site, which turns out, improbably, to contain a future Cairo Ritz-Carlton. Between the tidal energies of the daily commute and the ugly presence of the hotel’s massive construction pit, the initial impression is not of a protest that has changed the country forever but of something that has been submerged in the churn of everyday life.

Most days, the political activity is confined to the plaza’s southwestern corner, and on the December mornings I visited, it was occupied by just a couple of hundred people, mostly hunkered quietly down into tents, some of which bore the slogans of small, fragmentary revolutionary parties. These are the revolution’s most hard-core devotees, who are still here, almost a year after the crowds have left. It is a precarious existence: Last Tuesday night, when this remnant rallied to protest the ongoing military trials, they were beset by a group of thugs who beat them with baseball bats, fired live ammunition, and occupied their tents, which were later burned.

Near the encampment hang imposing, two-story-high banners, each displaying idolizing photographs of the martyrs, the young men who died fighting the regime’s security forces in Tahrir Square. For a while, in the immediate aftermath of the revolution, the faces of the martyrs were everywhere—you could buy revolutionary soap and revolutionary shaving cream. But even these early heroes are less celebrated now. “I was just communicating with one guy who lost both of his eyes—he used to work, and he no longer works,” Ghonim told me. “He got a lot of attention from people at the beginning. And then everyone leaves, and he’s still got no job.”

About twenty minutes away from the square, if you get lucky and traffic is moving, is the prosperous neighborhood of Mohandeseen, on the opposite bank of the Nile in the city of Giza. This is where Ghonim grew up, and when he walks through the streets, he is stopped frequently by worried men who grab his hand. The question he gets most often is the most basic one: What does he think will happen next? But there are also questions about the Muslim Brotherhood, the military. “People just want someone to tell them ‘Things are okay,’ ” Ghonim says. “ ‘There are others working on it. Don’t worry.’ ”

This has become increasingly difficult to do. Throughout the summer and fall, the protests had been steadily dwindling. But in November, a few days before the first round of parliamentary elections, the square had exploded. Protesters lobbed Molotov cocktails at the police, and for three days the demonstrations mounted. The state’s response was bold. The riot police swept through the square, long lines of cops holding plastic shields, behind them men firing tear gas and, occasionally, live ammunition from on top of armored Toyota trucks. “The fact that people died is very annoying to me; it just shows how incompetent those who lead us are,” Ghonim told me. “And it also shows that on the other side”—the revolutionary side—“we failed to create the leadership for this moment. At the end of the day, the revolution was against a school of thought, a mentality. And this mentality is still ruling the country one way or another.”

But to other observers, the lesson was more severe. The military “undertakes repression now because it assumes it has majority support,” says Michael Wahid Hanna, an Egypt scholar at the Century Foundation. It was after the violent protests in November that the counterprotest began in Abassiya Square. It may well be that in a country of 83 million people, the revolution never had the support of the majority. It certainly doesn’t now. “Let me say it bluntly,” says Salama, Ghonim’s friend. “A lot of people hate the revolution.” Some hard-core revolutionary activists believe that liberals like Ghonim abandoned the square too hastily, and that this has made it harder to sustain a movement against military abuses. “When Mubarak left, Wael Ghonim tweeted, saying, ‘Mission accomplished,’ ” says an influential leftist blogger and activist named Hossam el-Hamalawy. “Complete bullshit, in my point of view. There were people like myself who thought, Ha! We haven’t really changed anything with Mubarak stepping down.”

Ghonim is still on leave from Google, and when he is in Egypt, which is about half the time, he stays at his mother’s house. He and some of his close friends recently announced that they had formed an advocacy group, Our Egypt, to try to reframe the revolution’s public-relations campaign. But most of his political work has been less formal: trying to negotiate between protesters and the government when things get tense, visiting with neighborhood groups who want his help. When we sat down to lunch one day last month in an upstairs restaurant in Mohandeseen, Ghonim pulled out his iPad and showed me a photo; he and some other activists had gotten all seven presidential candidates into a room to try to persuade them to push the military for concessions. But the effort failed.

He started to scroll through the Khaled Said Facebook page. It has 1.8 million members now, and here Ghonim is trying to keep a revolution of the crowds, directed by the crowds, alive. Often a post will have attracted thousands of comments, but he will scroll diligently through them all. When he is thinking about a new stand to take on the page, a new direction to suggest, he will call up leftists, Salafists, friends, focus-grouping the idea, trying to discern where consensus lies. Ghonim is disdainful of liberals who are trying to rush the country along—one recent campaign that earned his disdain was in support of a 20-year-old blogger who had posted stylized nude photos of herself, a red ribbon in her hair, to make a case for free expression. “You have to respect the boundaries of the culture,” Ghonim says. “The page sort of needs to be a honey pot for everyone.”

Neither Ghonim nor the page took any position on the parliamentary elections. An endorsement might have helped shift “30 or 40 seats,” maybe 10 percent of the Parliament, he conceded, but it would have alienated too many of the page’s members. Ghonim has an absolute commitment to the crowd. “Maybe I’m in a denial,” he says. “I just think that if this is the decision that people make, that they want the Muslim Brotherhood to run the country, then this is the decision that we all have to respect. This is the people’s choice. This is democracy.” Sometimes the conservatism of his membership surprises even Ghonim. In December, the military commanders who run the country appointed an ex–prime minister named Kamal Ganzouri to be prime minister again, and Ghonim assumed that his audience would hate the choice, given the clear old-regime retrenchment. But he took a poll; 55 percent of his readers were in favor of Ganzouri.

“Ghonim is probably more in touch with Egypt than the activists, but it’s also possible that [his audience is] wrong,” says Hanna. “What you see in Egypt now is a thirst for stability. People are okay with crushing dissent, with military trials, with putting down the rabble. Looking to majority support in a country with that much illiteracy and state propaganda—there is a conservatism there.”

The Internet isn’t just a ham radio. It’s also a mirror: It gives a movement self-knowledge, and self-knowledge in a revolution is a complicated gift. We are accustomed to the idea of the unbendable revolutionary, wedded to his radical vision. Ghonim is a different model: a revolutionary who follows his followers. At the most important moments, Ghonim’s supporters supplied a bracing moral clarity, the conviction that the regime could not stand. But now, when the politics are more complicated, the crowd can reflect exhaustion, even moral deference. Perhaps there was something to be said for the ministers of the old regime; perhaps the Islamists would bring stability. Revolutionaries could once be willingly ignorant of what the people wanted. A revolution of the crowd does not have the same freedom. Sometimes the crowd imposes brakes.

Just before I arrived in Cairo, Ghonim had spent an afternoon visiting a poor neighborhood whose local community-watch organization, having been formed during the revolution to protect property from damage, wanted his help to lobby the government—for better trash collection and access to the city’s gas lines. Ghonim has been getting these requests with some frequency, and they encourage him. “Ownership,” he says. “A good sign of a changing Egypt.” The most subtly arresting images from the revolution came after Mubarak had been deposed and the crowds had dissipated, when small groups of citizens—two, five, ten people—had emerged on the streets, brooms in hand, and begun to clean up, as if to prove that the revolution had restored a sense of agency. “The revolution was not an event,” Ghonim says. “It is a process.”

To be optimistic about Egypt right now is to have faith that the very fact of participation matters, in some tectonic way—each time a person votes in a legitimate election, each time he encounters photographs of the martyrs rather than busts of the dictator. “The DNA of the revolution was that there was no one who said, ‘Go back down the streets now’ or ‘Go back to your homes now,’” Ghonim says. For a while, he had believed categorically that this is what had given the revolution its power. Now he is more circumspect. “The lack of leadership in the revolution, we’ll see whether that was the best thing for the revolution or the worst thing. History will judge.”

That morning, I had been with Ghonim when he went to vote for the first time in his life, at age 31, at a primary school near his mother’s home in Mohandeseen. His 23-year-old brother, Hazem, was with him, and so was an uncle, and he wore a light coat and carried an iPad. The entrance to the school was on a quiet, curving side street that police had blocked off from cars as a precaution against violence. That seemed a very distant worry. Overhead, there was the strained, echoing, tin-can-telephone call to noon prayer. There was nothing like the eruptive, valedictory joy from the first elections in places like Afghanistan or Iraq; when the men in front of Ghonim finished voting, they mostly looked at their watches and hurried off, eager to get back to work. Ghonim was in the line for three hours. “Democracy is slow,” I texted him, from a few feet away. “;-) slow but steady,” he texted back. I had been warned that he would be swamped by well-wishers, by people wanting to have their photos taken with him, but aside from a couple of handshakes, he was left alone. After some time, Ghonim pulled out his iPad and hunched over it, shuffling anonymously in line, toward the polling station and out of view.