The poster shows a solitary adolescent boy of a bygone era standing across the street from a Broadway theater, the Music Box, staring at its dazzling façade as if he were a burglar plotting to break into a bank. The scene is bathed in the gold-and-purple glow of curtain time, yet the block is as deserted as a Magritte streetscape: Everyone has taken their seats to watch the show except this one boy, who, for whatever mysterious reason, remains stranded on the outside looking in.

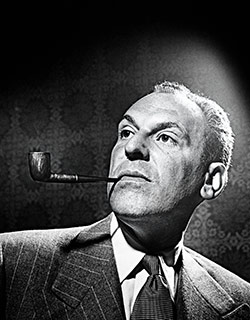

This dreamlike visual vignette of loneliness and longing, by the illustrator James McMullan, has been plastered around the city for weeks now, heralding the first stage adaptation of Moss Hart’s autobiography, Act One, written and directed by James Lapine and scheduled to open at Lincoln Center’s Vivian Beaumont Theater just before Easter. Most pedestrians probably haven’t paid it much heed. The show has no marquee stars, and in a late-season theater crush awash in familiar brands (Rocky, Cabaret, Aladdin), its profile is second-tier; Act One is less well remembered than A Raisin in the Sun, another of this spring’s revivals, though Lorraine Hansberry’s play and Hart’s book both made their acclaimed debuts in the same year, 1959. So faint is Moss Hart’s afterlife in the 21st century that few recall he was a show-business superstar for three decades—the co-author of two of the most successful comedies in American theater history (the Pulitzer Prize–winning You Can’t Take It With You and The Man Who Came to Dinner), the director of the original production of My Fair Lady, and the screenwriter of the enduring postwar movies Gentleman’s Agreement and the Judy Garland A Star Is Born. A half-century ago, Act One, a memoir that was his first and only book, spent nearly a year on the Times best-seller list, some five months of it at No. 1.

For the small minority that does know of Hart and Act One, the poster for the theatrical version evokes a powerful response. The book is “treasured in a way that is singular,” in the words of Tim Federle, a 33-year-old former Broadway dancer who has transitioned into a successful career as a writer with an Act One–esque tale of his own, Better Nate Than Ever, a novel for young readers about a stage-struck eighth-grader in a small town outside Pittsburgh who runs away to New York. But even among Federle’s theatrical cohort, Act One is obscure. “There are always like three guys and a lady in the cast of a show who not only know it but it’s the reason they got into the theater,” he says. The rest “may think Moss Hart sounds like a Muppet.”

In fact, Hart’s story is the Ur-text of neo-Broadway television soap operas Federle’s generation has appeared in or watched, like Glee and Smash. But the book’s devoted fan base isn’t limited to theater nerds. Terry Gilliam has told of how Hart inspired him to bolt the Midwest for New York, where he sought out a cartoonist hero, Mad magazine co-founder Harvey Kurtzman, and started on the path to Monty Python. Graydon Carter is an Act One fanatic who discovered the book while in high school in Ottawa. Another obsessive, the late New York Observer editor Peter Kaplan, toyed years ago, as I did, with the notion of writing a full-dress biography of Hart, only to be discouraged by the strenuous efforts of his widow, Kitty Carlisle Hart, to keep his archives and their presumed secrets under lock and key. (I ended up writing my own Act One–influenced childhood memoir instead.) Hart and his Broadway writing partner George S. Kaufman have also been an acknowledged influence on Woody Allen, plainly visible in his earliest plays and the films Radio Days and Bullets Over Broadway (itself coming to Broadway as a musical this spring). Another, if unexpected, Hart devotee is the novelist Ann Patchett. After she started a second career as an independent bookseller in Nashville two years ago, she said that “Act One is one of the best things about owning a bookstore” because, as she put it, “I can sell Act One to people all day long.”

I can guess her pitch. Hart’s memoir is one of the great American autobiographies because it gives a certain kind of reader hope. It says you can escape a home where you feel you don’t belong, you can escape a town you find suffocating, you can follow a passion (the theater, but not just the theater) that is ridiculed by your peers, you can—with hard work, luck, and stamina—forge a career doing what you love. However modest or traumatic your beginnings, you can find your way to Oz—and you don’t have to go back to Kansas anymore.

It’s a book I could not put down despite its adult girth when my mother gave me her Book of the Month Club edition to read, at age 10, in the year of its publication. Even then, Act One was a period piece. Set in the dozen or so years before the Great Depression, it unfolds against a show-business backdrop still not free of vaudeville and hokey stage melodramas—already a distant world in 1959. Since then, the book has survived despite the fading of Hart’s fame, despite later revelations that some elements of Act One were either fictionalized or pure myth, and despite the gradual emergence of the fuller, no less compelling Hart story that his widow tried to suppress until her death at age 96 in 2007. The more we learn about the truth of Moss Hart, it turns out, the more powerful Act One becomes, not just as a book but as a heroic act of generosity from a man whose heart and mind were breaking down even as he was writing it.

Act One was pointedly titled, since it told the story of only the first act of Hart’s life, culminating in 1930, when his first Broadway hit, Once in a Lifetime, opened at the Music Box. (Still extant on 45th Street, the theater currently houses Pippin.) He concludes the book with “Intermission” rather than “The End.” But it was the end. Just two years after its publication, Moss Hart dropped dead outside his new home in Palm Springs, California, at the age of 57. Yet his is one American life that has had an unexpectedly dramatic and productive, if posthumous, second act.

The first act was pure Horatio Alger. Hart was born in 1904 in what is now Spanish Harlem to immigrant English Jewish parents. It was “an atmosphere of unrelieved poverty”: His father’s marginal income evaporated when his menial profession of cigar rolling was mechanized. In the “bewildering battlefield of conflicting loyalties” that was his childhood, Moss was equally distant from his tyrannical mother, his defeated father, and a brother whom he regarded as an alien even though they shared a bed until Moss left home. His one soul mate was his aunt Kate, an unmarried eccentric with Blanche DuBois–like delusions of grandeur who would save her few pennies to buy theater tickets in the upper balcony for herself and, eventually, her young nephew. Kate, Hart writes, “always got to the theater early enough to stand in the lobby and watch the audience go in—in order, as she expressed it, to get all there was to get!” She bequeathed that passion to Moss. His “fantasies and speculations” were “always of Broadway,” he writes, even though he would not emerge from the subway to see Times Square with his own eyes until he was 12, an indelible coming-of-age tableau that opens Act One. When the quarrelsome Kate is later evicted from the household following a savage fight with Moss’s father, her banishment hits both Moss and the reader as the end of the world. The image of the aunt “dropping her beloved programs from trembling hands all over the floor” as she is cast out into homelessness and, ultimately, an untimely death is as rending as any leave-taking in Dickens.

Like his aunt, Hart loved books as well as the theater. To ingratiate himself with the tough boys in the neighborhood, he regaled them with the plots of favorite novels like David Copperfield and Dreiser’s Sister Carrie, whose heroine, not so incidentally, flees small-town Wisconsin as a teenager and wins theatrical stardom later in New York. Hart dropped out of school after seventh grade. To contribute to the family’s meager coffers, he worked long hours in a fur-storage vault that left him reeking on the long ride home underground each night, Broadway tantalizingly out of reach above. But for all the deprivation Hart suffered—of finances and emotional sustenance—Act One, like David Copperfield, is laced with humor. He introduces us to one memorable comic gargoyle after another, from “The Mad Cossack” (the horse-riding proprietor of an insolvent adults’ camp in Vermont where Moss works one summer) to the producer Gus Pitou, mocked as the “King of the One-Night Stands” because of his ingenuity at exploiting the Railway Guide to maximize hinterland tours of threadbare plays with bargain-basement “stars.” It’s Pitou’s hiring of Moss as an office boy at the New Amsterdam Theatre (now Disney’s domain, then Florenz Ziegfeld’s) that sets off the exhilarating chain of events leading Hart to his unlikely collision with the book’s most arresting supporting player, Kaufman, 15 years his senior and the leading commercial Broadway playwright of his day. For all Kaufman’s reputation as a public wit, he was in close-up awkward and eccentric, not to mention fearful of the most modest forms of human intimacy, whether handshakes or basic small talk. But he proved a true mentor, serving as Hart’s entrée not only to the theater industry but also to the epicenter of a New York literary scene ruled by Kaufman’s coterie at the Algonquin Round Table. Even so, Kaufman and Hart’s collaboration on Once in a Lifetime, a satire of Hollywood’s conversion to talkies that anticipates the film Singin’ in the Rain by more than two decades, was riddled with reversals and catastrophes. The play’s Perils of Pauline journey to Broadway triumph remains suspenseful no matter how many times you reread it.

What lifts Act One above other riveting backstage sagas and rags-to-riches success stories is the loneliness and sadness the hero has to overcome. “I have a pet theory of my own, probably invalid, that the theater is an inevitable refuge of the unhappy child,” Hart writes early in the book, no doubt knowing full well that his theory is valid. “Certainly the first retreat a child makes to alleviate his unhappiness is to contrive a world of his own,” he explains, “and it is but a small step out of his private world into the fantasy world of the theater.” In my own case, as a gloomy, stage-struck young child of divorce, Hart was the first adult I found who articulated some semblance of the unhappiness I felt. His story gave me the hope of escape, as it did so many others, whether they alighted on theater as a refuge or not.

That’s why the true climax of Act One is not the glittering Broadway opening night of Once in a Lifetime but its aftermath in Brooklyn. Flush for the first time, Moss swoops up his dazed mother, father, and brother to take them to new quarters in Manhattan, ordering them to leave with just the clothes on their backs and nothing else. After he sends his family ahead to a waiting taxi, he opens the tenement’s windows so that a raging storm outside can flood into their hovel of an apartment and pummel their old lives into oblivion. “I slammed the door behind me without looking back,” Hart writes. Or so, at least, he would try.

At the time Act One was published, You Can’t Take It With You (1936) and The Man Who Came to Dinner (1939) had aged into stock and amateur staples (as they still are) but were often viewed as sentimental relics or wisecrack-driven proto-sitcoms in a postwar American theater dominated by Tennessee Williams and Arthur Miller. A rare Kaufman-and-Hart stab at a more somber play, Merrily We Roll Along (1934), had been forgotten entirely (though it would resurface, much altered, as the basis for a Stephen Sondheim musical in 1981). The pair’s writing partnership had broken up by 1941, when Hart on his own wrote the libretto for Lady in the Dark, a groundbreaking musical extravaganza about psychoanalysis. But his subsequent efforts to write serious dramas solo, in the manner of his youthful heroes Shaw and O’Neill, were failures. He had not had a new play on Broadway since 1952, when his ponderous African drama, The Climate of Eden, expired in less than two weeks, and was instead directing light stage comedies by others. His current currency was most of all tied to his role in staging My Fair Lady, which had opened in 1956 and was on its way to becoming the longest-running musical in Broadway history up to that time.

Act One was a comparable smash, receiving raves on the front pages of the Times’ and Herald Tribune’s Sunday book reviews even as My Fair Lady repeated its New York success in London. But if this was a career apotheosis for Hart, it arrived at the end of another era, his era. The advent of rock and roll and of a new kind of Broadway musical, ushered in by West Side Story in 1957, was propelling pop culture in general, not to mention the New York theater, in directions unimagined by Hart’s generation. When the My Fair Lady team reassembled for a can’t-miss follow-up in 1960, Camelot, the critical and public reception was indifferent, the box office wobbly, and the ordeal of revising it during frantic out-of-town tryouts, Once in a Lifetime style, a likely factor in the hospitalization of its lyricist, Alan Jay Lerner, for a bleeding ulcer and Hart for a heart attack.

It was another heart attack—his third—that took Hart’s life during Christmas week of 1961. His passing seemed unimaginable; Kaufman had died six months earlier, but at the riper age of 71 and after a long professional silence. Both of Hart’s musicals were still alive and kicking on Broadway. The celebratory obituary on the Times’ front page drew heavily from Act One and made much of the latter-day Hart’s well-known personal extravagance and boldface-name lifestyle. An accompanying appreciation by the paper’s drama critic, Brooks Atkinson, who had known Hart since the 1920s, was headlined “An Enthusiasm for Life” and concluded with the observation that “he had and gave a good time everywhere.” After New Year’s, a standing-room-only audience packed the Music Box for a memorial tribute. The encomiums from Hart’s celebrity pals were also festive and frothy, but the last speaker, his editor Bennett Cerf, sounded one grave, if fleeting, note. “All of his life,” he told the crowd, “Moss Hart suffered periodic attacks of almost unbearable depression. Analysis provided only a partial cure.” Then Cerf moved on to jollier reminiscences, culminating in an anecdote about how Moss turned a mishap at “Bill Paley’s pool in Jamaica” into “the subject of a hilarious calypso song.”

Two years later, a slapdash film adaptation of Act One, written and directed by an old Hart friend, Dore Schary, with George Hamilton as Moss, sank without a trace. (There’s zero chance its jokey tone will resurface in the stage adaptation envisioned by Lapine, whose previous stage portrait of an artist as a young man was his libretto for Sunday in the Park With George.) Moss Hart’s cultural footprint started to shrink rapidly, though not that of Kitty, whom he married in 1946 and with whom he had two children, only 13 and 11 at the time of his death. Herself something of a self-invention—she had been born Catherine Conn to a Jewish family in New Orleans—Kitty Carlisle was an elegant singer who, before she connected with Moss, played the ingénue in the Marx Brothers’ 1935 classic, A Night at the Opera, co-written by Kaufman. In her long post-Moss iteration, she became a minor celebrity as a panelist on a prime-time game show, To Tell the Truth, and performed a nostalgic cabaret act into her 90s. But those of us who wanted to learn more about the husband whose autobiography had changed our lives could get nowhere with her. Some of Moss Hart’s papers, which had been deposited at the Wisconsin Historical Society, were embargoed for her lifetime. When profiling Kitty Hart for The New Yorker in 1993 during her tenure running the New York Council on the Arts, the writer Marie Brenner asked her, “Why have you never allowed anyone to write a biography of your husband?” Kitty answered, “He wrote his own,” as if Act One, whose final chapter took place 31 years before Moss’s death, told all. When Brenner raised rumors that Hart might have been gay, Kitty said that she had asked him point-blank during their courtship, “Are you homosexual?” and he had answered, “Absolutely not.” Kitty said that she “never gave it another thought.”

Speculation about Hart’s sexuality—of a sort that circled nearly every man in the theater in an era when homosexuality was criminalized and often closeted—had been common among his friends and colleagues for years. And Kitty’s defensiveness to Brenner only fueled the rumors. Among the items off-limits in Wisconsin was a yearlong diary Moss kept during their marriage, in 1953–54.

After Brenner’s profile was published, a writer named Steven Bach contacted me, seeking my help as a former Times drama critic in finding possible sources on Hart. He had decided to pursue a biography despite Kitty Hart’s roadblocks. I introduced him to my friend Arthur Gelb, a retired Times editor who had known and covered Moss when he was a deputy to Atkinson in the paper’s drama department in the 1950s. Arthur called a few surviving mutual acquaintances of the Harts, but Kitty had shut down every source she could.

Bach was himself a survivor of show-business turmoil and not one to retreat easily. He was the final production head of United Artists, the Hollywood studio that during his tenure released Annie Hall, Network, Apocalypse Now, and Raging Bull, only to be brought down in 1980 by an epic flop he championed, Michael Cimino’s Heaven’s Gate. His Hollywood career over, Bach became an author and a professor of film whose biographical subjects would also include Marlene Dietrich and Leni Riefenstahl, before his death in 2009. His first book, the 1985 Final Cut, an inside account of the Heaven’s Gate fiasco, is fittingly described by the critic David Thomson as “the best book ever written about the making of a movie.” Bach’s biography of Hart, titled Dazzler and published in 2001, would prove one of the best books ever written about Broadway, yet it is little known. Kitty Hart’s successful four-decade effort to thwart other would-be Hart biographers had the unintended consequence of further diminishing her husband’s cultural status and, with that, public appetite for a biography. While Dazzler received respectful reviews, they tended to patronize its subject as an anachronism not worthy of the effort.

Bach’s motive in writing Dazzler could speak for many Hart admirers: “I was a student growing up in the dreary middle of a drearier nowhere and felt life suddenly given color and light by the pages of Hart’s best-selling book, Act One.” His tireless reportage paints an even bleaker portrait of Moss’s childhood than Moss did. The young Hart was “a scrawny boy with bad teeth, a funny name, an odd way of talking, a father and brother who were crippled.” (They had, respectively, a withered leg and arm, neither mentioned in Act One.) Aunt Kate was not a colorful, poignant eccentric so much as a destructive psychotic. Contrary to Act One’s narrative, she lived on long after her eviction from the Hart household and resurfaced in a spiteful criminal incident aimed at Moss after he achieved success. Bach also discovered that Once in a Lifetime was not Hart’s first do-or-die Broadway break, as breathlessly presented in the book, but had been preceded in 1930 by a failed musical and, before that, by a Broadway-bound play, Oscar Wilde, whose announced production had been derailed by its producer’s death.

Bach’s most remarkable feat of sleuthing was to track down Glen Boles, who, as a young actor, had played the juvenile in the original touring company of You Can’t Take It With You. Boles was still alive—he died at 95 in 2009—and told of a long-lasting friendship and passing sexual relationship with Moss that began during that show’s rehearsals. Bach was conscientious about not pushing the evidence any further than was warranted. He quoted Boles as saying Hart “may have been experimenting” in their liaison: “Sexuality per se was less important to him than wanting to love and be loved. He used to say, ‘If I could love somebody, I wouldn’t care if it was a man, a woman, or a pig.’ ” There is circumstantial evidence that Moss had other gay liaisons as well in his bachelor years; among other clues, Bach found that Hart spent four and a half months on a cruise with Cole Porter, his wife Linda, and “the Porters’ moveable family, all of them”—like Cole—“from Yale and all of them gay.” Bach also discovered that Moss turned up as a thinly disguised character, a star playwright propositioning a young actor in a suite at the Waldorf-Astoria, where Hart indeed lived in the ’30s, in a best-selling gay pulp novel of 1970 by Gordon Merrick, once a young actor in the original Broadway cast of The Man Who Came to Dinner. Whatever Hart’s sexual orientation, or confusion about it, his long conversations with Boles about his experiences with psychoanalysis inspired the young actor to go to medical school on the G.I. Bill after serving in World War II. He set up a psychiatric practice in New York that lasted well into the ’90s and that centered, Bach writes, “mostly on young gay men trying to adjust to their sexual orientation in a still hostile social atmosphere.”

The upsetting revelations in Dazzler are not about Hart’s sexuality, but about the terrifying bipolar disorder that he had likely inherited genetically from his grandfather, a beloved figure briefly glimpsed early in Act One. Crippling depressions had long tortured Moss, as Cerf had alluded to at his memorial. The paralyzing bouts of despair were famously followed by manic shopping sprees, whether to buy himself gold trinkets at Cartier or to secure lavish new apartments and houses that he redecorated and stuffed with antiques before abandoning them for the next. In Act One, Moss writes of how his younger, poorer self “would stroll into the lobby of a fashionable hotel and walk around for as long as I dared, making believe that I belonged there.” But later, no luxuries could sate him. A much-repeated joke, variously attributed to Kaufman and Alexander Woollcott, had it that Hart’s over-the-top summer estate in Bucks County was “just what God would have done if he had the money.”

There was nothing funny about Hart’s mental illness, however, and the treatment he received for it was a tragedy. He became a devotee of a Manhattan analyst, Dr. Lawrence Kubie, known for collecting celebrity patients, including those like Tennessee Williams and Vladimir Horowitz, whom he sought to “cure” of what was then considered the disease of homosexuality. Kubie’s practices were destructive: He told Williams that he would benefit by giving up writing. To treat Hart, he sometimes convened two sessions daily—running from 50 minutes to two and a half hours—and subjected him to electroshock treatments every other day. On top of this regimen, Kubie was a regular in the Harts’ social lives and a supplier of seemingly indiscriminate dosages of prescription drugs. That Hart was able to function at all in this period—let alone direct My Fair Lady and write Act One—was a miracle, albeit one for which he probably paid with his life.

Kitty Hart ignored the publication of Dazzler, but perhaps to counter it she finally cooperated with another Moss Hart biography, by Jared Brown, published in 2006, and gave him access to the 1953–54 diary that was denied to Bach. But it was too late. Hart’s shelf life as a book-length subject for anyone except cultists had expired; Brown’s book attracted little notice and few reviews.

After Kitty’s death, the restrictions on access to Moss’s archives were lifted, and a researcher can judge the full evidence firsthand. The diary, written as Moss was turning 50 as “an exercise in discipline for no other eyes but my own,” is shocking not because of anything it has to say about Kitty, the Harts’ marriage, his sex life, or their children. Quite the contrary; Moss’s love for his first real family is apparent on nearly every page. What’s upsetting is his punishing depression. It stalks him even as he goes about the professional chores he did carry out in this period, including his repeated trips to Hollywood to meet with Garland and the director George Cukor on A Star Is Born, his directing of Kitty in her first Broadway starring vehicle as an actress, and his early stabs at writing a memoir.

Hart’s private views about his circle and his career are almost entirely antithetical to what would emerge in his autobiography five years later. In the diary, he is in an almost perpetual rage at the producer Joe Hyman, who is presented as his most loyal friend in Act One, and is nearly as angry at Kaufman, with whom he was still locked in a neurotic son-father relationship. The same Moss who in Act One will write with awe about his first encounter with his cultural idols at a Kaufman-townhouse tea party in the late 1920s—Edna Ferber, Harpo Marx, Alfred Lunt, Dorothy Parker, et al.—writes venomously of these figures and their successors in his diary of the 1950s. Hart often couldn’t abide Irving Berlin, Ira Gershwin, Rodgers or Hammerstein. Describing a New York party for Cukor at which “all the regular faces” included Audrey Hepburn (who “looked anything but dazzling that afternoon”), Truman Capote (“in a constant state of ill temper”), and Greta Garbo (“very pinched and old”), Hart concluded: “Here are the people mentioned in the newspapers and magazines of the world and how silly and shallow they seemed compared to the people I really admire.” But in 156 pages, Hart expresses admiration for almost no one beyond his immediate family. His bitchiness toward some of the Harts’ closest friends may in the end have been Kitty’s biggest motive for keeping the diary secret.

The words that dominate the entries are “depressing” and “depressed,” as in sentences like “I wander through the days in a haze of depression and inertia, unable to think or write a word.” Describing a walk down the thoroughfare he glorifies in Act One, he writes, “Broadway, God knows, is tawdry enough on a brisk autumn or winter evening, but on a hot summer night, it is almost intolerably ugly.” When he starts to pursue a project in the still newish medium of television, he is quickly discouraged. “Once again, it is fully apparent,” Hart writes, “that there is no aspect of show business that isn’t pure hell.”

You’d think that to reread Act One in the context of this diary and Dazzler would be disillusioning for anyone who has spent much of a lifetime admiring the “Moss Hart” of his memoir. But that’s not the case. While Hart sometimes fictionalized his own story, “it didn’t matter if it was literally true,” as Bach wisely concluded, because the book’s core is true. Hart’s self-mythologizing is within a long-established tradition of American letters dating back to the mythmaking of The Autobiography of Benjamin Franklin and Samuel Clemens’s reinvention of himself as Mark Twain. Such fictionalization can be taken too far—Lillian Hellman’s appropriation of another person’s life in Pentimento—but Hart’s improvements, like those in the autobiographies of Americans as diverse as, say, Lincoln Steffens, Malcolm X, and, more recently, Barack Obama, are not so much to mislead or self-aggrandize as to pump up the drama in a fable of difficult struggle and ultimate redemption. As D. H. Lawrence once observed, Americans “revel in subterfuge,” preferring that truth be “swaddled in an ark of bullrushes, and deposited among the reeds until some friendly Egyptian princess comes to rescue the babe.”

That Hart wrote a book showing that it was possible to escape so horrific a childhood—at least until Intermission—is a gift to lonely and troubled kids everywhere. And it was not an easy gift to deliver, since it required him to quarantine the sadness of his second act to keep it from contaminating his genuine joy and pride in his escape at the end of the first. Adult readers, if not young ones, will recognize that the happy ending is by definition provisional anyway. No one can escape the scars of childhood simply by slamming the door. But that’s another story.

Indeed, it’s hard to read Act One without thinking of an earlier, darker, fictional variation on its tale—the 1905 Willa Cather story “Paul’s Case,” which has so many echoes in Hart’s book that it seems likely that at some point he read it and absorbed it. “Paul’s Case” is the Act One he might have written had he wanted to succumb to his depression. It tells of a lonely, opera-loving high-school student in Pittsburgh whose only joy is working nights as an usher at that city’s Carnegie Hall and whose only friend is a young actor at a local stock company. Paul’s nocturnal love affair with the opera and the theater, Cather writes, was his “fairy tale, and it had for him all the allurement of a secret love.” When, after work, he stands before the glittering hotel that houses “all the actors and singers,” he wonders whether he’s “destined always to shiver in the black night outside, looking up at it.” And so Paul steals some cash and runs away to New York, where he sets out on what can only be described as a Moss Hart binge: He shops for a flashy new wardrobe, buys a scarf pin at Tiffany’s, secures a suite at the Waldorf-Astoria, and falls in with a Yale undergrad, “a wild San Francisco boy,” with whom he stays out until dawn. Paul is psychologically fragile (“his eyes were remarkable for a certain hysterical brilliancy”) and, like Cather, he may well be gay (“there was something about the boy which none of them understood”), but in any case he is doomed. Even a writer as farsighted as Cather could see no way out for her lost boy in a story first published in McClure’s magazine the year after Moss was born.

It’s a long way from “Paul’s Case” to a contemporary coming-of-age tale like Better Nate Than Ever, in which a probably gay eighth-grade theater geek runs away from Pittsburgh to Broadway and finds that there is a place he can feel at home after all. That’s a cultural sea change that has played out in America over a century. As a large new audience of theatergoers and readers may soon discover, the rocky road between then and now was never illuminated with greater sympathy or at greater cost than by Moss Hart, both by how he lived his life and how he chose to tell his story in the radiant pages of Act One.