This year’s Democratic presidential race is so interesting in so many different ways. There’s the exceptional length and geographical breadth of the electoral drama. Then there’s the fact that the two superstar contenders are almost identical programmatically, yet so different as human beings—that is, as “brands.” By which I don’t only or even mainly mean that one is a woman and one is black.

But then, of course, there is that. And because of the candidates’ unprecedented race and gender, we who observe and obsess professionally were bound to look more closely than ever at which sorts of voters are voting for and against each of them. Entirely apart from what I think of Clinton or Obama as potential presidents, this election is a rare, grand, nationwide, real-time social-science experiment, an irresistible opportunity to test how tens of millions of Americans feel about race and gender and all the rest.

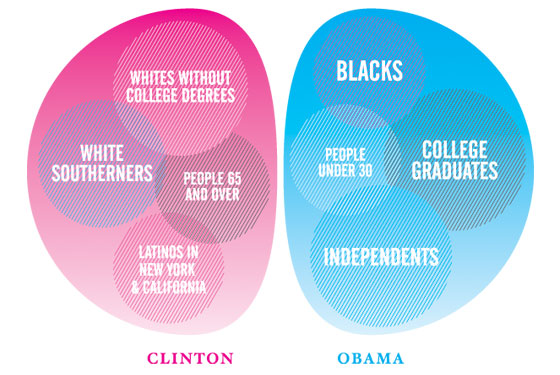

As each new tranche of exit-poll data has poured in, a set of conventional wisdoms has emerged among the pundits. And like so many other things about this election cycle, the demographic CW has proved much iffier than it seemed even a week ago.

Having just spent days geekily digging through the numbers, I’ve found that many of the new shorthand home truths have been highly overstated all along. But I’m also dumbstruck by how powerfully, consistently determinative a few variables have been—how demography really is destiny.

If you are very young or highly educated or male or black or live in a western state never owned by Mexico, you’re quite likely for Obama. And conversely, if you’re a white woman of a certain age, you’re very probably going to vote Clinton.

This determinism works out exactly as expected among most of my friends, acquaintances, and family. My next-door neighbor in Brooklyn is an eightysomething white Catholic woman with a high-school education; she voted for Clinton. For my 60-year-old professor sister, her postgrad education trumped her age and gender, and she voted for Obama—as did my children (18, 19). And me? I’m an overpaid (check) man (check) with a college degree (check) who grew up in the Great Plains (check); I really had no choice in the matter.

For me these predictabilities call into question—seriously—just how much any of us exercises free will. Adolphe Quetelet, the father of statistical social science, wrote in the mid-nineteenth century that for criminals, the crime is “the result of the circumstances in which he is placed. … Society prepares the crime, and the guilty are only the instruments by which it is executed.” Same with voting in 2008 as with stealing a loaf of bread in 1842. And for every contrarian among us who decides to flout his or her circumstantial demographic destiny—if I had pulled the lever for Clinton, for instance—another of my demographic ilk was bound to step in and vote the right way, to ensure the total conformed to the essentially predetermined number.

Thus does poli sci begin to resemble a harder science—quantum physics: Each of us voters is like a subatomic particle, our individual behavior at any moment “indeterminate,” never absolutely predictable, but as a practical matter, in the aggregate over millions of repetitions—electrons spinning, voters voting—we behave in a supremely predictable fashion. Matter does not spontaneously dissolve because the atoms all happen to move apart at a given moment, and 65 percent of southern college graduates (give or take 4 percent) will vote for Obama. It seems we possess only free-ish will. “Yes we can”? Yeah, maybe, but only if it has been decreed in advance, by the demographic gods.

One of the most profound drivers of this election has been the generation gap between old white people and very young white people, those 65 and over versus those under 30. In the most important primary states of the Northeast and Midwest, between 62 and 64 percent of the old have voted for Clinton, and between 32 and 35 percent for Obama. Young whites have behaved in precisely the opposite way. (And last week, in Virginia, Obama won the under-thirties by three-to-one.)

No demographic force, however, is more uncannily consistent in this election than being black. Since South Carolina, if you’re African-American, you’ll vote for Obama 81 percent of the time, plus or minus 5 percent, unless you happen to live in a candidate’s state—a staggering 98 percent of black men in Illinois voted for the black man from Illinois.

For whites, however, one’s demographic destiny is the result of a much more complex and interesting algorithm that combines race with geography. It seems there are three distinct regional flavors of white people. In most of the Deep South, only 27 percent of whites (plus or minus 3) voted for Obama. In most of the rest of America—the East from New Hampshire to Virginia, the older Midwest, and nearly all the land we won from Mexico—43 percent of whites (plus or minus 7 percent) voted for Obama. And everywhere in the Lewis and Clark part of the country, from the Great Plains to the Pacific Northwest, gigantic majorities of white people voted for Obama.

But much of the other conventional wisdom is dubious. Clinton is said to appeal to more conservative, less-educated working-class voters, especially Latinos, and Obama to educated, well-to-do liberals—the Dunkin’ Donuts vs. Starbucks trope. Yet in fact, income hasn’t really correlated strongly and consistently with which Democrat one prefers. Nor does simply being Latino, or liberal or conservative.

In Virginia, for instance, the difference between college graduates and non-college-educated voters was vanishingly small, and in Maryland, the less educated were more pro-Obama. And in the populous northeastern states that Clinton won, such as New York, she won majorities of the college-educated.

The Clinton supporter and CNN pundit Paul Begala said on TV last Tuesday night that Obama had “lost every income group below $50,000 a year” on Super-Duper Tuesday. Right? Wrong: In fact, he won among those people in Georgia, Illinois, Missouri, Utah, and elsewhere.

The other big piece of not-entirely-true conventional wisdom is that Clinton is everywhere beloved and/or Obama rejected by Latinos. In fact, Clinton’s share of the Latino vote has ranged from a high of 73 percent in New York to just 43 percent next door in Connecticut. Go figure. In fact, Obama won the Latino vote in Connecticut, and in Arizona he did better among them than among whites.

Among self-described liberals and conservatives, the results are even more all over the map. Last week, for instance, Obama’s greatest strength in Virginia was among “conservatives,” but among “moderates” in Maryland, where Clinton did best among “liberals.” And in New York, Obama actually beat Clinton at both ends of the ideological spectrum, among the quarter of Democrats who call themselves either “very liberal” or “somewhat conservative.” (As a supporter of Obama who, depending on the issue, wanders from very liberal to somewhat conservative, I don’t find this crazy.)

It’s pretty much the same mixed-up situation with religious observance. In California, Clinton won among people who go to church more than once a week, while in New Jersey Obama won among those most frequent churchgoers.

And speaking of that state just across the Hudson: You are so weird, New Jersey. In Jersey, Obama didn’t win among college graduates or the rich. And if you were to look at the state’s voter numbers in a blind test, you’d swear they were from the Deep South: Only in places where people have southern accents—and New Jersey—did Obama get less than 30 percent of white women’s votes, or Clinton an absolute majority of the votes of white men. I’m hereby adjusting my stereotype.

Last week, however, the political weather changed. In Virginia and Maryland, two of the strongest fixed demographic patterns started to break, like frozen rivers thawing as spring approached. Maybe this, finally, is what momentum looks like. In both states, Obama won convincingly among white men—by 58 to 40 percent in Virginia, the capital of the Confederacy. And, apparently for the first time, Obama won among old voters, too. Only a single group, white women, stuck with Clinton.

Thus, it seems, demographics are destiny, but in this election really only in three particular cases: African-Americans drawn irresistibly to one of their own, white women of a certain age drawn irresistibly to one of their own, and young whites drawn irresistibly to youthfulness and the thrill of the new. Duh.

We have a bit of a double standard about this, of course. On the one hand, who can fail to be heartened by the spectacle of majorities of white southern guys voting for an African-American? We coo approvingly when certain people behave against type. I was even pleased (and slightly shocked) that 43 percent of black women in New York voted for Clinton.

Yet on the other hand, we selectively suspend our disapproval of the historically downtrodden as they behave according to type. We’re sympathetic to all the white women voting for Clinton, and all the black people voting for Obama. But we also hope—don’t we?—that this is another awkward, inevitable moment in our long, long march toward a society in which nonwhite and non-male presidential candidates aren’t thrilling by virtue of their race or gender.

The general election, of course, will be a whole new, fascinating phase of this sociology experiment—though the prospect of McCain vs. Obama is vastly more interesting than McCain vs. Clinton. I think we know pretty much exactly how the latter would set up: The main mystery would be whether the gender gap might break 20 percent. Between McCain and Obama, however, so much would be fresh territory: young versus old, two viable voting options for the (white, male) Bill Clinton Democrats, a possible bifurcation of independents and peeling away of moderate Republicans, and so on. As Hillary Clinton said a couple of months ago, now the fun part starts.

Email: emailandersen@aol.com.