This is not the end, nor even the beginning of the end, but it is, finally, the end of the beginning. And what a relief. Even though Hillary Clinton refused to let everyone exhale until she said we could, Obama won. Period.

So why am I not utterly elated? It’s partly the weird slow-motion victory, a slog punctuated by a few thrilling nights (Iowa in January, the Potomac and Wisconsin primaries in February, North Carolina a month ago) but no knockout punch, no definitive high-five moment. Mainly, however, it’s because now, without any imminent do-or-die threat to Obama’s candidacy, my suppressed anxieties about him are bubbling to the surface. That is: I fear that he will lose to John McCain…and I wonder, if he does win, whether he can be nearly as good a president as some of us have had the audacity to hope.

I’m amazed at how many people I know are surprised by my reckoning of the rough road ahead. Their blitheness about November only increases my gnawing dread. And it’s not just people here in the New York Democratic echo chamber who think Obama’s a cinch: Last week the Internet politics bettors were giving him better than 3-to-2 odds. But to me right now a hundred bucks wagered on McCain ($286 back if he wins), sad to say, looks like a smarter bet than Obama ($100 gets you $164).

Sorry to be a buzz kill. It’s as painful for me as it is for you. How do I worry? Let me count the ways.

1. I pick losers. Two of the three presidential candidates I’ve enthusiastically supported during the primary process—Gary Hart in 1984 and Bill Bradley in 2000—were whacked early. The only one who reached the convention was, like Obama, a decent, antiwar, moderately anti-Establishment Midwesterner who improbably came out of left field in 1972 to win the nomination, thanks to the support of young people (like me) and adults of the kind I would become. George McGovern, of course, lost to Richard Nixon in a landslide. Ever since, I’ve felt culpable for my bit part (McGovern’s Nebraska youth coordinator!) in rebranding Democrats as the party of naïve softies, and wary of assuming that one’s own political enthusiasms are scalable. I had the excuse of being only 17, but for Hillary and Bill Clinton, who both worked in the McGovern campaign as twentysomethings, it’s clear that 1972 was profoundly chastening. Maybe her depressing selling proposition these last six months—that being a successful presidential candidate requires being much more like Nixon than McGovern—will turn out to be correct.

2. Hillary wants him to lose. Her speech Tuesday night was certainly Nixonian—grim, grudging, disingenuous, self-pitying—and she made no move to stop her throng from chanting “Denver! Denver! Denver!” Indeed, she has knowingly exacerbated and extended her diehards’ ferocity and resentment. She long ago lost the nomination, but her reluctance to concede (not a month ago, not last Tuesday night, not until the weekend) has already sucked some general-election votes away from Obama, and I believe she will keep doing so, pro forma endorsement notwithstanding. The central premise of her campaign was that unless she became the nominee, McCain would win in November; therefore, her credibility depends on Obama’s losing. It’s like the psychopathology of the Sunni insurgents in Iraq: They have no chance of returning to power any time soon, but they can make life hell for their victorious sectarian opponents.

3. His national polling’s not as bad as the Clintons say… Hillary’s people were still arguing last week that the polling data on Obama versus McCain and Clinton versus McCain should convince superdelegates to nominate Hillary. Naturally, they considerably overstated the case. In fact, according to three-dozen nationwide polls this year by a dozen organizations—including the Pew Research Center, Reuters/Zogby, ABC News/Washington Post, CBS News/New York Times, USA Today/Gallup, and NPR—Obama runs on average a little stronger against McCain than Clinton.

Yet there are three important national polls suggesting that Obama is a slightly weaker general-election candidate than Clinton would have been. The latest Newsweek and the L.A. Times/Bloomberg surveys show Obama tying and beating McCain, respectively, but the win is by a smaller margin than Clinton’s would have been. And although Gallup’s daily tracking polls for the past three months show both Democrats neck-and-neck with McCain, she averages a couple of points stronger.

So it’s six of one, a half-dozen of the other—in any case not a show-stopping argument that the delegates must reverse course and nominate Hillary Clinton. But not very reassuring about Obama’s strength, either.

4. …But he may have real problems with independents and women. The deeper I dive into the data, the more anxious I become. Back in February, Mark Penn, then Clinton’s chief strategist, declared that Obama’s support among independents “would evaporate relatively quickly once he faced the Republicans.” Or even, as it happened, once he faced the Clintons for several more months. Between February and May, according to Pew polling, the percentage of independents with a favorable view of Obama shrank from 62 to 49 percent.

So far he’s holding onto his base—among people under 30 and college graduates, his support has actually increased. Two of the unenthusiastic constituencies, old people and Catholics, don’t seem to be growing more antagonistic. But the two other relatively Obama-unfriendly blocs, female and working-class whites, appear to be turning against him—especially white women. In just one month, according to Pew, Obama (and Hillary Clinton) virtually erased the gender gap: In April, he was beating McCain among white women, but by May, McCain was running ahead of Obama by 8 percent.

5. Presidential elections are Civil War reenactments—in which the North can lose. Amazing but true: For those of us trying to predict electoral votes in this election, 1860s cartography—Union states and border states and Confederate states—remains salient. And the balance of sentiment concerning the Negro Question still powerfully determines which states may be red and which blue.

Obama will be elected president if he wins eighteen of the twenty Union states (that is, all but Indiana and Kansas—and he has a long shot at both of those), plus the two most “northern” of the five border states (Maryland and Delaware), plus Washington (which wasn’t a state during the Civil War). McCain, conversely, will probably win every Confederate state.

The problem for Obama is that three of the biggest northern states—Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Michigan—sometimes swing southern these days. It’s practically impossible to see how he becomes president without winning two of them. All three, not to put too fine a point on it, contain blocs that bear a certain psychographic kinship with Civil War Southerners—that is, insular white traditionalists who are suspicious of the African-Americans in their midst and resent the ascendant economic and cultural power of self-righteous urban elites. Thus the Clintons’ argument that an Obama candidacy could founder in these key states happens, alas, to be true.

True humility is a disqualifier for winning the presidency, but the appearance of humility can be essential, and Obama’s surpassing self-confidence can come across as preening self-regard.

He is apparently strongest in Pennsylvania, between 2 and 9 percent ahead of McCain. In Ohio, the latest poll has Obama well ahead, but in the five previous surveys, going back to early April, he was behind. In the Michigan polls from May, he’s trailing McCain. And in all the inland border states—West Virginia, Kentucky, and Missouri—which Democrats sometimes win (and Clinton very well might’ve), he looks to have a chance only in Missouri, thanks to its big cities and 12 percent African-American population.

So if he wins two of the three big northern swing states but loses the whole Deep South, then he has to prevail in Colorado (where he’s ahead), or take Nevada and New Mexico (where the polls have him seesawing with McCain), or get lucky and win Virginia.

The paths to victory are there, and Obamaniacal turnout among blacks and the young may push him over. But by historical standards, it really would have been easier to piece together a winning electoral map with Hillary Clinton as the nominee. Politically, nominating Obama (as Bill Clinton said) is something of a roll of the dice.

6. Is he “elitist,” too condescending and glib and remote and full of himself? I don’t find him so—but then again, I myself am an elitist who can seem condescending and glib and remote and full of himself, so who am I to judge? I worry that more moments like his passive-aggressive put-down of Hillary at her cutesy-wounded debate moment—“You’re likable enough”—will continue to lose friends and alienate people. I also worry that his impolitic cosmopolitan shorthand—frustrated small-towners who cling to guns and religion and blame immigrants for their economic distress, energy-glutton Americans who expect developing countries to reduce their carbon emissions—will recur. True humility is a disqualifier for winning the nomination and certainly the presidency, but the appearance of humility, at least as a tactical posture, can be essential. It certainly worked for George W. Bush. Obama’s surpassing self-confidence can come across as preening self-regard. Thus, perhaps, his bungled outreach to Elizabeth Edwards, as reported by my colleague John Heilemann. Will he make the uncool, insecure middle-American majority feel even more so?

7. His instincts that attract me amount to weaknesses as a candidate. Too often, instead of deflecting inconvenient questions, Obama answers them directly and fully. And while the U.S. should, of course, be confident enough to have conversations with foreign enemies, any Democratic nominee carries the baggage of several decades of national-security wimpiness. Voters implicitly understand that any Democrat will be more reasonable and prudent and diplomatically engaged than Bush or McCain; it’s an impression of convincing toughness Obama has to sell, and I’m not sure he can do it.

8. The evil in men’s hearts. Every time I watch him work the crowds, I cringe a little, dreading the lurching nut and pop-pop. Any assassination is horrific; the murder of Obama could be a national trauma beyond reckoning. Similarly, beyond my own preference, I think an Obama loss in November would be particularly disheartening for the country. It would amount to a national statement concerning our racial divide: Nah, we can’t.

9. Two words: Jimmy Carter. Not since John Kennedy, almost half a century ago, has a senator, or a Democrat without a southern accent, won the presidency. (Although both candidates this year are senators, and both drawl-free.) Maybe Obama will be the 21st-century JFK. But maybe he’s the new Jimmy Carter. From national anonymity to the nomination in no time; a Cinderella story the media loved; running against a discredited GOP to turn the page on a national nightmare; a lack of foreign-policy experience; idealism and trustworthiness that congealed, after he won, into irritating naïveté and sanctimony. I tend to believe Obama is wiser and more worldly than Carter, and I relish every anecdote about his stone-cold toughness as he muscled into Chicago politics. My hope is that, as George W. Bush turned out to be no Ronald Reagan, President Obama would turn out to be no Jimmy Carter. But the Carter analogy can’t be ignored.

10. Washington’s hopeless. I’ve thumped for post-partisan fair-mindedness for years. I was hopeful about Bill Clinton—a fiscally disciplined, welfare-reforming Democrat! But as we all saw in Clinton’s first term, Washington may simply be irredeemable. Even though an American majority is purple, Congress and national politics have become structurally, dysfunctionally polarized between red and blue during the last two or three decades. In other words, an Obama administration might simply prove, by its failure, that George Bush and Hillary Clinton’s grisly, cynical, unyielding paradigm is the one we’re stuck with.

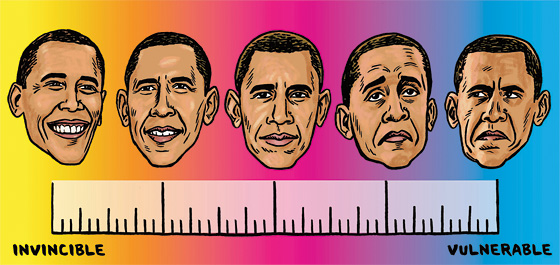

There; I’ve confessed. But all that notwithstanding, I’m thrilled that Obama will be nominated, and fervently hope he wins the presidency. As I would’ve—well, maybe not “fervently”—had Clinton been the nominee: On Supreme Court appointments and health-care policy alone, the choice between Democrat and Republican is easy. And on geopolitics, I’m far more convinced that President Obama would summon up the requisite steel and shrewdness than I am that President McCain would become sufficiently nuanced and diplomatic. Like the great conservative pundit James Lileks, I want a president who “does not appear to have a heart ruled by sentiment.” McCain is a hothead and a hot-dogging never-say-die hero, whose conception of himself and America entirely derives, God bless him, from a heart ruled by sentiment. Whereas for all his eloquence and uplift, Obama’s cool, unruffled Spock-like rigor is what makes him, in my view, presidential, maybe even Lincolnian. Unfortunately, it’s this same quality, maybe as much as his race, that will make it hard for him to get elected in November.

SEE ALSO:

How Clinton Supporters Might Be Obama’s Next Big Problem

Email: emailandersen@aol.com.