On Wednesday, July 12, the day Hezbollah raided Israel and captured two Israeli soldiers, Ramsay Short, the young British editor of Time Out Beirut, was at the opening-night gala for the new rooftop Sky Bar nightclub in the Beirut waterfront exhibition center called BIEL. Ricky Martin, 50 Cent, and Paul van Dyk had performed at the center over the previous months to thousands of lithe, sweaty Lebanese fans. “It’s a fantastic place, very Miami, very Fashion TV–style glamorous,” Short said. He was in an exuberant mood that night, chatting with the chef Anthony Bourdain, who was there on his first visit to the Middle East to film an episode of his show No Reservations. The city Short had lived in since 2001 was enjoying a vitality it hadn’t seen since the early seventies.

But even amid the fizz at Sky Bar, there was a mood of unease. As fireworks lit the harbor and hundreds of guests gorged on free food and drink, Israeli jets flew watchfully overhead. The next morning, Israel launched air strikes on Beirut and southern Lebanon, and soon after, Hezbollah began firing rockets into northern Israel. By the end of last week, southern Lebanon and southern Beirut had been devastated, and several northern Israeli cities had been hit by rockets, killing fifteen civilians; over 350 Lebanese civilians had been killed, and thousands of Americans were in the process of being evacuated, including Bourdain, who was holed up in a hotel called Le Royal until Thursday morning. “We were treated with incredible hospitality and pride everywhere we went for the first two days we were there,” he said. “In a moment, it turned to shit.” And a notice went up on the Time Out Beirut Website: “Beirut’s favourite entertainment and listings magazine is now suspended. Lebanon is being, once again, used as a battleground for a war that neither its government nor its people want. They are killing our city.” Or something more than a city: In a country that had been experimenting with becoming a cosmopolitan Middle East democracy (albeit one with Hezbollah in the government), much more was at stake than the nightlife.

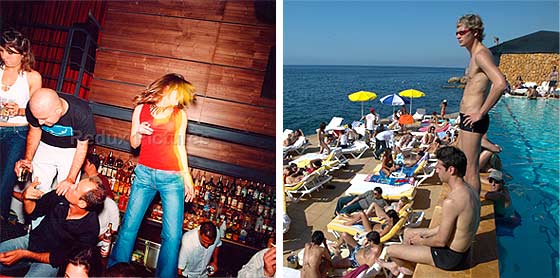

To many Americans, the word Beirut is synonymous with warfare, not “Fashion TV–style glamorous.” U.S. citizens were forbidden to visit Lebanon for a decade after the horrific suicide-bombing of a U.S. Marine barracks in 1983, and when the ban on travel was lifted in July 1997, the bulk of visitors were Lebanese-Americans heading to see relatives. But in recent years, a new lifestyle began to rear up in Beirut. Kids from Dearborn and other Arab-American enclaves came home with reports of Mediterranean sunsets, decadent discos, fabulous food, high-end beach clubs that were “L.A. times ten,” Roman and Phoenician ruins, red-tile-roofed hill towns, and snowcapped mountains. Curious travelers went to see for themselves, and journalists soon followed. It was a sort of exotic, frayed Utopia.

Warren Singh-Bartlett, Wallpaper’s Middle East editor, lives in Beirut. He’d stopped through eight years ago when backpacking and ended up moving there. “I love Beirut because it’s the most improbable city in the world,” he says. “When you think of where it is, when you think of the deep divisions in Lebanese society, when you think of the wildly different ways of living life here—it doesn’t make sense, it shouldn’t work. But it does. There’s a kind of anarchy here that’s beautiful. It’s creative, it’s so different to anyplace else in the Middle East.”

A Wallpaper-ish design culture was blooming. Architects like Philippe Starck and Steven Holl have projects there, and American magazines feature homegrown talent like Bernard Khoury, Nabil Gholam, Annabel Karim Kassar, and Nada Debs. In the current issue, Singh-Bartlett described Beirut as “a real-world Legoland.”

The Manhattan architect Joe Serrins had been part of the boom. Three years ago, he took on a million-dollar job designing a 5,000-square-foot apartment by the marina. Beirut took him by surprise. “I didn’t expect there to be camels roaming around, but I didn’t expect it to be so much like Miami,” he said. “Or Cannes.” He was supposed to fly there last Thursday to wrap up. Needless to say, the trip did not happen. ”It’s incredible now to think that they’re blowing up the airport,” he said. “It’s so tragic and frustrating. They put so much energy into rebuilding, and now this?”

Even before the current crisis, Lebanon teetered between competing realities. In 2005, former prime minister Rafiq Hariri, who’d been behind much of the newfound openness, was assassinated in a car bombing. Most put the blame on Syria, and, in fact, international outrage at Hariri’s death helped Lebanon achieve what it had not been able to do in 30 years: get Syrian troops to withdraw from the country.

Meanwhile, many Americans still thought of it as unchanged from the eighties. Maha Chehlaoui, an actress who lives in New York, is astonished at how few of her American friends have asked her how her friends and family in Lebanon have fared over the past two weeks. “I’m convinced it is because they think Beirut has been under fire nonstop since 1975,” she says. “Ten years of peace is a blip on the radar, I guess. After all, ‘those people’ are always bombing each other,” she adds ironically.

Last Wednesday, Leila Buck and her husband, Adam Abel, a young Brooklyn couple, interrupted their holiday in Beirut and escaped to Damascus. Abel, who is a nonpracticing Jew, said, “Being American has been very difficult this last week, because just in a simplistic way, you’re hearing and feeling bombs dropped and you know they’re stamped with MADE IN AMERICA.” He continued, “In Lebanon, because it’s such a layered culture, people are going to ask you where you’re from, and not in a dubious manner; it’s done in a very cultural way. So when people would ask me where I’m from and conversations would become more intimate, I would always tell them I was American, and if they asked further, I told them my family was Jewish, and I was always embraced. There is a clear distinction between the feeling about the religion and the feeling about Israel.”

Singh-Bartlett was in Dubai on assignment when the bombing started. He flew to Damascus on Saturday and paid a driver $100 to get him home. They had to use the side roads since the highway was bombed out. Singh-Bartlett lives in Ashrafiye, the Christian section of Beirut, which contains the Rue Monot, lined with nightclubs and cafés. Much of the Israeli bombardment of Beirut has been concentrated on the poor southern suburbs, but last Wednesday morning, bombs dropped on two trucks in Ashrafiye that had apparently been mistaken for grenade launchers.

Singh-Bartlett does not defend Hezbollah—far from it. He points out that Lebanon is not Hezbollah. “Hezbollah could, with a single action,” he said, “determine the domestic and foreign policy of an entire country independently of that country.”

He was appalled that the city that had been stepping jauntily into the future was being so rudely pushed down. “Everywhere you go in the Middle East, they all want to be Beirut,” he maintains. “That’s exactly why it’s so disgusting that it’s being dismembered in front of me, why it’s being destroyed in front of me. People think of Beirut as a dark, scary place full of dangerous people. That’s not the city I live in. This is the place all the Arabs come to be free, this is where they come to think, this is where they come to play. This is where they come to try new ideas. And then if they like them, they take them home with them. Beirut makes things possible.”

The question is whether this sense of Beirut itself is still possible. Time Out Beirut’s first issue had only come out in April. “Time Out is a magazine about arts and culture,” Ramsay Short says. “But everything has been canceled and half my staff have left the country.” Last year, he published A Hedonist’s Guide to Beirut. “Maybe sales will go up,” he says. “It’ll almost be a collector’s item of what was this high point, what now seems like a dream.” Next: Is Robert De Niro Selling Nobu?

More on the Israel-Lebanon Conflict:

100-Person Poll: A Random Survey of New Yorkers of Different Faiths on the Conflict

What Our Politicians Are Doing Wrong

by Kurt Andersen

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.