For almost every stage in the development of New York, there’s a parallel imaginary city, full of willowy towers, weightless bridges, and parks where the tulips are always in bloom. The latest entry in the urbanism version of fantasy football has made an appearance in a storefront next to Grand Central Terminal: an exhibit of possible—but improbable—futures for the Hudson Yards, Manhattan’s last frontier. The MTA, which owns the site and wants a deal that will wipe away its fiscal problems, asked developers to submit proposals. Five came in, and now the agency is inviting the public to scrutinize them—to weigh the benefits of a Morgan Stanley headquarters against a new Condé Nast building, consider a floating pier and an aerial running track, and compare plantings, grass, and boardwalks. Visitors can drop a comment in the appropriate shoe box, and the agency will duly ignore it. The pictures of glittering towers and digital families gamboling on Astroturf lawns are intended to convince people that the plans will be evaluated on the basis of architecture, design, and urban planning. But since the MTA has so far withheld the crucial financial facts, such as how many billions each developer has budgeted, the public’s opinions on design minutiae don’t carry much weight.

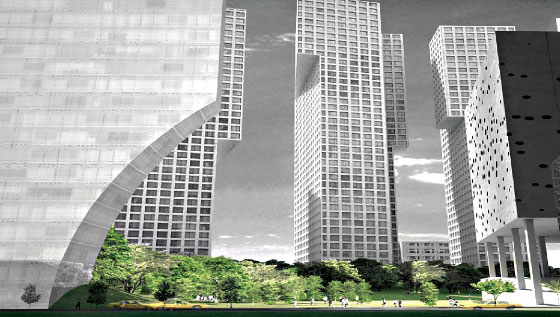

All five developers have dreamed up grimly elegant and deeply depressing visions. The most architecturally bold, in a glum, Gotham City sort of way, is the scheme that Steven Holl designed for Extell. It’s a phalanx of towers—including a threesome that merges into a tuberous top 90 stories up in the air—plus a low-rise Corbusierian slab that sits atop columns and looks as though it had been riddled with bullet holes. The most preposterously high-tech solution to a nonexistent problem is the Durst/Vornado plan’s “automated people-mover” that wafts pedestrians onto the site from points east. The goal should be to grow midtown organically westward, but if you connect the Yards to Penn Station by an airport-style shuttle, you wind up merely dramatizing the divide.

Zoning regulations and the MTA’s request for proposals predetermined the project’s overall shape and scale: 26 acres, 12 million square feet of offices, shops, and apartments, a platform over the train tracks, assorted parks and plazas, plus a concert hall or museum, all arranged in a pair of megablocks separated by Eleventh Avenue. A wedge of greenery (working title: Hudson Boulevard) will drive south from the Lincoln Tunnel between Tenth and Eleventh Avenues, swerve right at West 32nd Street, and widen into a lawn encircled by a cluster of skyscrapers and edged by the West Side Highway. It’s a developer’s dream: a cleanish slate on a big lot. Those were the conditions that gave us both the original World Trade Center, which few loved during its lifetime, and its next incarnation, which few would call a triumph of Big Planning. Hudson Yards is a project that makes ground zero look modest, and the one sure thing is that the final result will look like none of the current conceptions. At least that’s a comforting thought.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.