Al Sharpton can’t help himself. Here he is: suited up in a banker’s three-piece, a Churchill-size cigar between his fingers (“the power look,” he says), and anchored in a club chair at the Grand Havana Room, the members-only stogie club that hovers above the clouds, on the top floor of 666 Fifth Avenue.

“Here, check this out,” he says, resting the cigar with a thud. He fishes in his pants pocket, produces a cell phone, pushes a few buttons, and passes it over for a listen.

The voice sounds familiar. “Hey, Al, this is Hillary Clinton, and…” Is it really her? Yep. Clinton is actually calling Sharpton for—pinch yourselves, folks—campaign advice. She wants to know what issues she should raise in an upcoming debate at Howard University. The focus is on black issues, and, well, who is a better judge of black issues in America than the ubiquitous face of them?

Sharpton has the cigar back in his fingers now. He wants the phone back. “Here,” he says, making sure to save the message. “Now, check this out.”

Another voice. “Al, this is Barack Obama…” Obama! Seriously? The senator also wants advice about the debate at Howard. Sharpton has calculated the values closely. “Hillary called three days before the debate,” he says. “Barack called like three hours before.”

And on the surface, that’s partly what this primary season comes down to for Sharpton: a race to see which candidate can kiss his ring the most, the fastest, and with the most sincere pucker. With a black candidate and the spouse of “the first black president” in the race, the jockeying to secure the black vote in the primaries has never been more intense. All of which puts Sharpton in demand. “In the end,” he says, “they may all hate my guts. But it’s the reality of the landscape … how much they need me and how bad. I’m sure right now they know they need me.” Though many have said that Sharpton’s brand of identity politics is obsolete, citing Obama (not to mention the ongoing investigation of the reverend’s finances) as evidence, Sharpton isn’t worried. “Ten years ago, they said Colin Powell was going to make Jesse obsolete. And ten years before. They’ve always had a Barack Obama. There will always be a more inside, acceptable black they will say makes us obsolete. I worry about that as much as James Brown worried about Sammy Davis making him obsolete.”

Around this time last year, it was a good bet that Sharpton would endorse Hillary Clinton. Within Hillary’s vast campaign, insiders thought Sharpton would be recruited as a priceless tabloid mercenary who could launch broadsides against Obama on that one taboo issue where he is vulnerable: his blackness. (“Ain’t too many of us grew up in Hawaii and went to Harvard,” Sharpton says.) Last January, Sharpton had a closed-door meeting with Bill Clinton at the former president’s Harlem offices. Afterward, Clinton’s staff came away with the impression that they had already secured Sharpton’s endorsement. When Sharpton’s people found out about this, they rushed to back away. No, they told Clinton’s staff, Sharpton had not promised Bill his endorsement of Hillary. Sharpton’s explanation? “Politicians hear what they want to hear. They think a cordial meeting is the same as ‘I want to support you.’”

Until recently, Sharpton’s relationship with Obama has been more aloof. Sharpton has also been underwhelmed by Obama’s campaign. “He never came off as a fighter,” he says, a strategy that he thinks has hurt Obama with a key demographic: black women. “Black women like a fighter. Even if you’re fighting a fight that is not my fight, I will believe that you might fight my fight. And to come off as ‘I’m all right with everybody’ doesn’t give people who want a fight a comfort level. I want somebody who’s at least a little upset with somebody, because I’m mad as hell. If you’re not mad, how do I get passionate about you?”

Sharpton thinks Obama should take more cues from his wife, Michelle. He still thinks about the time he bumped into her at a recent Chicago fund-raiser. He claims the conversation went like this.

“How you doing, Mrs. Obama?”

She’s tall, and looked down at him. “I’d do a lot better if we had your endorsement.”

Sharpton tried to play dumb. “What do you mean?”

“We need your endorsement. I’m just telling you straight out: We need your endorsement. What are you going to do?”

Sharpton didn’t know what to say. “I’m like, ‘Uh, well, duh.’ I mean, she was like a sister back in Brownsville, where I grew up!”

Barack Obama’s campaign headquarters is located on the eleventh floor of an office building in downtown Chicago. If there was once hesitation here about engaging in a lovefest with Sharpton, those jitters are long gone. “Reverend Sharpton is always welcome, and we look forward to his continued support and counsel,” says one Obama staffer. If Sharpton does join the Obama movement, the question for Obama’s advisers will be, How much of the stage will Obama be willing to share? In many ways, Sharpton embodies what Obama’s campaign has been running against: the same old race-baiting politics run by backroom demagogues. How could Obama be the candidate who moves “beyond race” when the firebrand behind the Tawana Brawley scandal is out stumping for him?

If Sharpton joins forces with Obama, he will also collide (again) with the family that raised him: the Jacksons. Sharpton is still bitter about Jesse Jackson, his mentor, and Jesse Jackson Jr., the congressman who serves as national co-chair of Obama’s campaign, for overlooking Sharpton’s presidential candidacy in 2004 (who didn’t?) and endorsing Howard Dean. During that race, Sharpton launched a public scourge against Jackson Jr.—he called Dean supporters “Uncle Toms.” For his part, Jackson Jr., who did not respond to requests for interviews, was seen during the race passing around a story that linked Sharpton’s campaign to Republican operative Roger Stone.

But that bad blood is nothing before the division between Sharpton and Jackson père. “What’s gone on with me and Al,” Jackson says, “is much too serious to discuss in public.” Sharpton will talk about it. “He was in many ways the same kind of father I wanted,” he says. “He said no. I said fine.” The lingering beef became so heated they refused to campaign together for John Kerry in 2004 or even travel on the same campaign plane. Such ill will is something Obama might want to avoid—although Jackson seems to have caused Obama enough damage on his own by endorsing him earlier in the year, then claiming Obama was “acting like he’s white” (for not traveling to Louisiana for a demonstration) and more recently claiming that all the candidates (save John Edwards—who in fact is the one who calls Sharpton most of all) “have virtually ignored the plight of African-Americans in this country.”

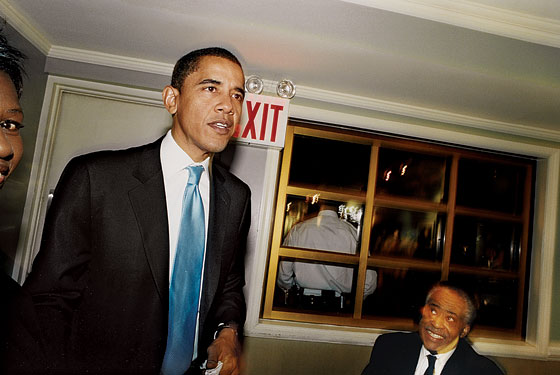

Obama calls Sharpton more now. He called before the Howard debate, called before the Congressional Black Caucus dinner to make sure Sharpton had a copy of his speech before he delivered it, called Sharpton’s radio show as a “secret guest” on October 3, to wish Sharpton a happy birthday, and called a few weeks ago because he was coming to town for a fund-raiser at the Apollo. Obama wanted to hang and talk. Sharpton suggested Sylvia’s, the soul-food capital of Harlem.

No problem. “I’ll pick you up,” Obama said.

Sharpton was impressed. A lift! With Secret Service! “His internal polls must show he’s having trouble in black communities, and that just talking to me could help,” Sharpton mused.

Sylvia’s was mobbed with press. Obama played up his southern-fried charm (“Now, I want plenty of hot sauce”) and he kissed babies and made long, clear eye contact with people, and the bomb of charisma he let off in the room (“C’mon,” he’d say, “let’s do another picture”) seemed to annoy Sharpton. He kept tugging at Obama’s arm, pulling him into the other room, where they sat at a table. Obama gobbled down fried shrimp in front of the cameras (“Hold the photo, I don’t want to have any grease on my lips,” he said, and one lady barked out, “Yes, you do”), as the always-dieting Sharpton watched. They talked about Obama’s wife, Michelle. She wanted to come, Obama said, but couldn’t make it. They talked about Obama’s speech. Did Sharpton get a copy? Yes, he got a copy. They talked about his diet. How, Obama wanted to know, did Sharpton manage to lose so much weight? “I do the treadmill, eat light,” he said. Sharpton’s cell phone annoyingly went off. Then it was time for Obama to leave.

Inside his own SUV, Sharpton was beaming. He imagined the headlines the next day and all the early-morning calls from the other candidates that would come. He imagined Bill Clinton calling. He broke into his best Arkansas accent. “Now Al, about that hate-crime legislation, the way I think we oughtta craft that…”

“Mr. President, just a minute, I’m in the shower. Can I call you back?”

“Well, I’m right in your living room. I just had to see you. I had the Secret Service open the door. They’re good at that.” Sharpton couldn’t stop laughing. He did more Clinton, going into that soft, easy twang. “I’m making eggs for you. Turkey bacon and eggs. We’ll eat right here.”

A few days later, his cell phone did ring. And when Sharpton boards his Justice Express for a three-day bus tour through South Carolina next week, the first guest scheduled to ride with him, he says, will be Bill Clinton.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.