The retrospectives could have been written already, to be touched up slightly as January 1, 2010, closed in. After eight years as mayor, Michael Bloomberg would have been remembered as the billionaire political neophyte who calmed a shaken New York in the crucial months after September 11 and helped guide it back to economic health. He would have been the mayor who shrugged off howls of protest and imposed a smoking ban that will save thousands of lives, created 311, and hired the gifted police commissioner who drove crime rates down to unimaginable lows. The reviews would also note Bloomberg’s losses—the 2012 Olympics, congestion pricing—and they’d incorporate his response to the great Wall Street bust of 2008. On balance, he’d have been judged a great success.

Now Bloomberg’s legacy will be much different. That’s one reason three of his closest aides were against challenging term limits. If Bloomberg succeeds in winning four more years, pushing back his exit until 2014, his first-term achievements will seem like ancient history; his second term will be a footnote. Instead, he’ll be staking his mayoral reputation on how he muscled his way into a third term and what he did with it. No matter how much Bloomberg claims that he’s doing this for the kids and that sticking around has nothing to do with his ego, he’s well aware of his place in history. And it’s about to sink or soar like the Dow.

Bloomberg will try to embellish his credentials on two main fronts. The first is control of the public-school system. Way back in 2001, Bloomberg declared he wanted his mayoralty judged on whether he improved education, and his biggest legislative victory was in getting Albany to put him in charge. But that law sunsets in June. The campaign to renew it was going to be tough anyway, because while test scores and graduation rates are up somewhat, parents are chafing at the test mania behind the numbers. Unions representing the teachers and the principals are likely to fight even harder to roll back mayoral control now that the same mayor is angling to be the one in control.

Then there’s the city’s financial health. The Wall Street mess handed the mayor a powerful, and legitimate, proximate motivation to reach for a third term. Yet the downturn also touches on Bloomberg’s mixed economic-development record. Losing the Olympic bid was the most spectacular failure, but Bloomberg has also been bogged down at Hudson Yards, his Willets Point overhaul is in question, and Coney Island may be reclaimed by the ocean before anything significant is built there. Bloomberg’s physical legacy is indirect: His revamping of zoning regulations led to a boom in office towers and condos … which may sit empty. A third term would allow Bloomberg a chance to jump-start his agenda, but he’d be trying to do it during a recession.

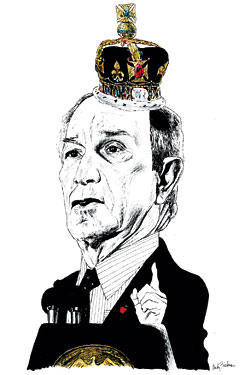

Right now, Bloomberg is so popular, and the city’s economy so unsettled, that his bid for a third term is very likely to be successful. But his new campaign raises questions about who Bloomberg really is—the “Boy Scout” described by loyalists who wants to serve the greater good, or the imperial ruler who knows better than everyone else and has the money to get his way. If, a year from now, the city’s economic picture isn’t so gloomy, Bloomberg will argue that his prudence is what saved us. But he will have also opened up an avenue of political attack: Keeping him on the job won’t seem nearly as urgent, and Bloomberg III will seem purely the product of his ego-stroking billionaire pals. Congressman Anthony Weiner nearly pulled off a Democratic primary upset in 2005 by positioning himself as the champion of the outer-borough middle class. If Weiner stays in the contest this time, he could exploit Bloomberg’s ties to the city’s corporate elite.

But if New York’s political history teaches anything, it is humility in trying to predict the future—even two weeks from now, let alone in November 2009. The last time we installed a mayor for a third term, the economy was prosperous and big happy things seemed within reach. During his third inaugural address, on January 1, 1986, Ed Koch announced he was going to vanquish homelessness, but mostly he cracked jokes and basked in the glow of a crushing election victory. Nine days later, the Queens borough president, Donald Manes, was found behind the wheel of his car near Shea Stadium bleeding from self-inflicted knife wounds. Koch did indeed build thousands of apartments in his third term. But he was also deeply depressed by the corruption scandals that swirled around him during those final years, and he left office in a racial storm. Bloomberg is a very different personality, in different times. But as he announced his decision last week, the tasseled black loafer on the mayor’s right foot pawed at the podium. Even Mike Bloomberg was nervous.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.