It’s not surprising that in the last three months of 2008, the U.S. Bankruptcy Court in New York (Southern District), which covers New York City, recorded 139 filings for Chapter 11 as compared with just 30 in the same period the year before. But those figures hardly reveal the depths of hopelessness. In recessions past, bankruptcy lawyers say, Chapter 11 was meant to buy businesses a little time to pay off their debts, restructure their operations, and stay afloat. That’s not what’s happening this time. “In this cycle, we are seeing fewer restructurings and more liquidations or quick sales,” says Saul Burian, managing director of the investment bank Houlihan Lokey Howard & Zukin. This is probably because reorganization costs money—from $10,000 (mom-and-pop pizzeria) to $1.4 billion (Enron)—and troubled businesses can’t afford it. “If you go back before 1980, bankruptcies were not financed. You filed for bankruptcy, and you survived by using your own cash flow,” notes UCLA law professor Lynn LoPucki, a leading bankruptcy authority. “Modern bankruptcies are done by financing, but in the current credit crunch, [businesses] are having difficulty finding anybody who will make these loans.” Put simply, “there is not financing available for the reorganization process,” says Manhattan bankruptcy lawyer Lawrence Gelber of Schulte Roth & Zabel.

Bankrupt businesses are leery of talking about liquidation for fear of frightening off potential investors. “We need to hold our cards close to our vest right now,” says Jamie Lamm, head of the Ninth Avenue recording studio Fearless Music, Inc., which filed for Chapter 11 in December. “It’s definitely a restructuring, but we’re not sure if it’s with an asset purchase involved or what.” If the company’s assets are mostly their creative talent, they might just liquidate right off the bat. “Consultants, financial planners, design companies, graphic design, web design, advertising—they’re vulnerable and choosing not to pursue Chapter 11,” says bankruptcy attorney Stephen Starr.

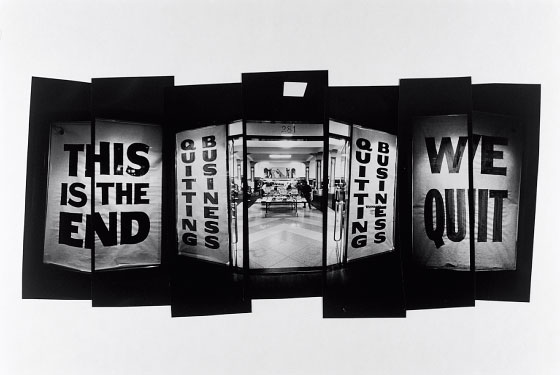

Keith Cox, who opened Cox Nissan in the North Bronx eight years ago, isn’t sure he can reorganize. “It could run over $100,000,” he says, and his sales dropped last year to 1,200 vehicles from about 2,000 in years before. His profit margin, he says, is below one percent, and he recently pumped $4 million into a new showroom and other upgrades. “I don’t know that something can be done.” Others have already given up. Standing in the mostly empty boutique Jewels by Victoria, a few blocks from the World Trade Center site, David Shabot, the store’s former manager, dismissed any talk of restructuring. “No, no. Business has been going down since 9/11. Things got worse and worse. And then, well, it got impossible.”

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.