“Let me make you this promise now,” declared Mayor Bloomberg in a particularly spirited moment of his most recent State of the City address. “We won’t cede an inch to the squeegee men.” Sounding almost Giuliani-esque as he embarked on an attempt to be elected to a third term, he proposed a new state law that would make your seventh “quality of life” violation in a year an instant felony.

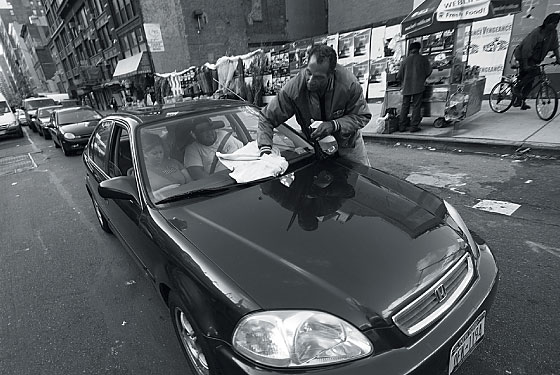

His predecessor, of course, nearly obliterated those urban scavengers who would wash your windshield at a traffic light and seek payment afterward. But once in a while, a spotting will occur—at the Second Avenue entrance to the RFK Bridge, say, or Watts Street at the Holland Tunnel. And as the current economic recession sends people scrambling for income, legal and illegal, one wonders whether the squeegee men will return in force.

“Most of us are too scared to come back,” says Leroy, a longtime Harlem denizen who nonetheless spent a recent cold night on Eleventh Avenue in Hells Kitchen, looking for a slushy corner with enough puddles to produce windshield splatter. “You take a lot of risks stepping out on the street. Cops will get you fast. You’re better off selling drugs.”

Leroy and his friend Charles “cleaned glass” in Manhattan for much of the nineties, and they speak of hustling with great pride. “Man, you really felt you were doing something for people,” Leroy shouts above the noise of the passing cars. It’s also a developed skill. “You got 60 seconds, sometimes less, to get to a car, clean six windows, maybe get a few bucks, and then get out of the way. No sir, not easy!” And all this without holding up traffic, which can bring about a police response.

“When you took the squeegee away, you took away people’s livelihood,” says Charles. “A lot of us hit the pipe and got into crime.” A few found new work. Leroy got part-time gigs at car washes near Yankee Stadium (a logical transition, when you think about it). But the work is never steady, and the pay always under the table. Charles turned his sights toward recycling, making about $200 per week scavenging for cans, and taking occasional janitorial jobs for small businesses—$25 a night to clean floors, counters, and bathrooms.

Both men roam Harlem and the Bronx, staying in shelters or abandoned buildings—they prefer the latter, since you don’t have to get out of bed at 6 a.m. And they come together every few weeks to clean glass. The money isn’t great: Each hoped to make $50 that evening, although as the weather warms they think they could make up to $100. Mostly, they do it to avert depression. “It’s just a way of making you feel like you have a purpose,” Charles mutters, cleaning off his squeegee, wiping splatter off his forehead, and getting ready for the next potential customer. “And this economy is so bad, a lot of people give you a nod because you’re not giving up.”

Leroy thinks the recession has even made cops more forgiving, something a few officers admitted off the record. “They look at me and it’s like they understand. It’s been a long time since a cop ever gave me that look.”

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.