Five years ago, David Geffen took a few prominent New York Times journalists to dinner at Gabriel’s. Hollywood’s richest man was just launching his failed campaign to buy the Los Angeles Times. The talk at the table focused on Geffen’s vision for the paper.

“He was explaining what his interest in the L.A. Times was,” recalls one of the dinnergoers. “I remember that he was pretty altruistic. He gave the ‘I want to save journalism’ speech. I remember him saying he didn’t care if he made any money out of it, he just wanted it to be good. It was heartening to hear anybody talk in those terms, but I was hardly convinced that he was the messiah.”

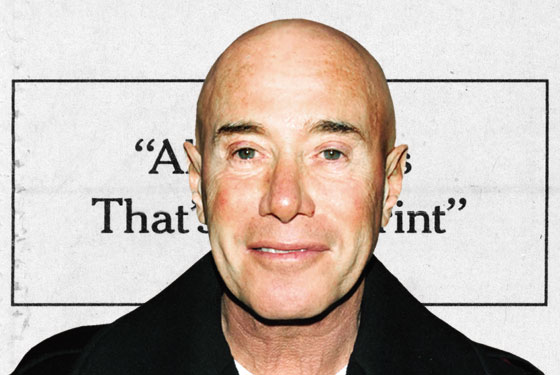

And now, presumably out of the same messianic impulse, he’s trying to save the New York Times. According to sources familiar with the situation, four months ago, the brilliantly strategic Geffen, 66, who calls himself “semi-retired” after leaving DreamWorks SKG, was rebuffed in his offer of a $250 million loan to solve the Times’s emergency cash-flow problem. Instead, Arthur Sulzberger Jr.—his family owns all of the voting stock—went with Mexican billionaire Carlos Slim Helú, who’s not supposed to have any ambitions to take over the paper. The same could not be said of Geffen, who according to various somewhat conflicting reports, discussed buying out the paper’s biggest outside shareholder, Harbinger Capital, as part of a gambit to turn it into a nonprofit—a secular church of good journalism, which he could found and endow.

Whether or not he actually has that intention, he could afford it: He ranks No. 110 on the Forbes global rich list, with a net worth of $4.5 billion. But obviously this wouldn’t be a business decision. Geffen grew up in Brooklyn, where his mother owned a corset shop. Today he might co-own a 454-foot yacht with Larry Ellison, but the Times has always held a special place in his aspirational cosmology. Plus, possibly, he’s a bit bored.

“He’s alert and alive and open to stimulus,” says fellow mogul Barry Diller (the two worked in the William Morris mailroom together). “I think somebody called him up and said ‘Would you be interested in owning 20 percent of the New York Times?’ Hmmm, maybe.”

More than most rich men, Geffen is fully a creature of the media. He’s unintimidated by it, loves journalists, and loves manipulating them, alternately subtle, seductive, and bullying; most love him right back. He returns phone calls and spins stories dramatically, usually to advance his interests, under the shield of “background.” When his friend Jeffrey Katzenberg was battling his boss at Disney, Michael Eisner, suddenly the Times reported that Eisner “has few close friends” and that Katzenberg was going to quit if he wasn’t treated better. All this came from Geffen.

He has nurtured mutually beneficial relationships. Geffen first went public with his attacks on the Clintons and threw his support to Barack Obama in his friend Maureen Dowd’s column and Geffen’s views became big political news.

Which makes it difficult to imagine how Geffen, if he were to actually buy the Times, could resist seeing it as his instrument. “The key question is, would he have the self-discipline not to use it for his personal loves, vendettas, whatever?” says the source from the Times. “For people who haven’t been in journalism, they think that if you own something, it’s yours to do with what you want.”

“David is not on a quest,” says Diller. “Believe me, if he was, he’d own it.” Still, “he is genuinely interested in newspapers. For him, it’s a creative challenge.” And that’s what he’s after. “David’s living a great life…You have to understand, David’s never had a job. When he focuses on something, he focuses intensely, but he’s the essence of someone who travels light.”

Geffen responded to a list of questions with a light e-mail: “Everything is great, thanks for asking. I am not going to talk about this at all, as it is counterproductive.” In any case, he’s probably already gotten much of what he wanted: He gets to enjoy the flurry of attention for his good intentions without having to confirm them, and he doesn’t get saddled with a bad business. An expertly played press moment, as usual.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.