The gorging on Michael Jackson’s corpse had only just begun when news came that another one of Quincy Jones’s beloved but troubled “children” had died: Vibe magazine. Launched in 1993, Vibe was a radical idea at the time—putting black stars on the cover while inviting white folks to the party, too. Jones, producer of meaningful music and culture-changing television (The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air, MADtv), was the perfect goodwill ambassador for such a project. Admired by black folks (who forgave him his procession of white girlfriends and wives) and genial and nonthreatening to white people, Jones had facilitated a tremendous number of crossover stars. He was beginning to rest on his not-inconsiderable laurels, taking meetings by the pool in his Bel Air manse (where a humongous 28-times-platinum Thriller plaque hung on the wall). He could bend someone’s ear at a party in the Hamptons and before you knew it, a media enterprise was sent spinning off into the mix. Vibe! A black Rolling Stone, man!

I was chosen—controversially, considering that I was a 29-year-old white (gay) man—by Time Inc. to be the founding editor. After I had handpicked a diverse and politically correct group of writers and editors, we set about the task of trying to figure out what should be in a magazine that was supposed to be about hip-hop but wound up being about much more than hip-hop because hip-hop is about much more than, well, hip-hop.

One thing we knew was not hip-hop in 1993 was Michael Jackson. That was the year 13-year-old Jordan Chandler accused Jackson of putting “his hand underneath my underpants” during sleepovers, among other creepy allegations. Many things are still in dispute from that time, but not the sad fact that Jackson was having pajama parties with his new 13-year-old best friend. Jackson’s slide into dermatological self-hatred accelerated around then, too: The child star who had become the greatest entertainer of all time had suddenly morphed into a powdered geisha. To top it off, one of Jackson’s hit songs at the time was “Black or White,” as in: “It don’t matter if you’re black or white.” And here we were, covering a pop-cultural movement that was built on fuck-all-y’all black self-acceptance. If hip-hop had a tagline, it would have read: It matters if you’re black or white.

I made it my mission to keep Jackson off the cover of Vibe, though Jones gently pushed for it several times during my two-year tenure. I knew he wanted to help him rehabilitate his image. Jones and Jackson went way back: Jones had produced Jackson’s first solo album and then the eighties megahits Thriller and Bad. I’m sure it pained him to see Jackson flail.

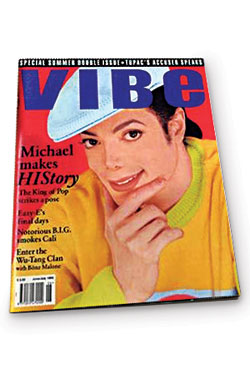

It was a different cover dispute that caused Jones and me to part ways. I had moved heaven and earth to get Madonna to interview Dennis Rodman and pose with the super-phreaky sports sensation for a cover shoot. But for the first time, Jones put his foot down. This was not the image he wanted Vibe to project. When he forbade me to run it, I quit. A few months later, Jackson appeared on the cover wearing a mustard-yellow sweater and a blue dude lid. The cover line read: THE KING OF POP STRIKES A POSE.

In retrospect, what’s funny about all the arguments over who was “legit” enough to “represent” on the cover of Vibe is how antiquated they now seem. Sooo early nineties. We weren’t aware of it then, but hip-hop was already well on its way to subsuming mainstream culture. Soon enough, Rev. Run would have a reality show, Ludacris would be rapping about Obama, Jay-Z and Beyoncé would be the king and queen of the music world, and, ultimately, Vibe and Michael Jackson would be history.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.