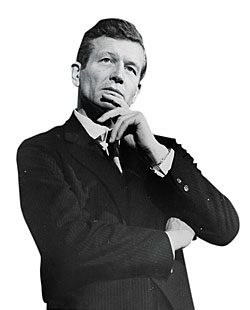

The mayor, a nominally Republican but socially liberal denizen of the Upper East Side, promulgates a vision of New York as a fresh, fun place, a city of glamour, leisure, and efficiency. He promotes biking, welcomes tourists, rebuilds Yankee Stadium, and courts Hollywood to film here. But he also displays a talent for angering working-class whites and alienating teachers. That description might apply to Michael Bloomberg, but it’s actually a sketch of one of his predecessors, John Lindsay. From 1966 to 1973, the tall, blue-eyed charmer with Robert Redford looks steered the city through riots, strikes, and financial decline, and his two wild and frustrating terms as mayor are due for some reevaluation.

In many ways, we live in the city Lindsay imagined but couldn’t deliver. A 1970 New Yorker cartoon shows a midtown street jammed with café tables, potted plants, and couples strolling in the middle of the street. “I’ll bet Lindsay never dreamed this would happen,” reads the caption. But that’s exactly what he dreamed, and while it seemed laughable then, it has lately come to pass.

Bloomberg might not want to claim the mantle of a mayor who was famous for falling short. The way to the fiscal crisis of 1975 was paved with Lindsay’s fine intentions. He fought crime, and it rose. He acceded to the unions’ unaffordable demands. By the end of his first term, the columnist Murray Kempton wrote, “the air is fouler, the streets dirtier, the bicycle thieves more vigilant, the labor contracts more abandoned in their disregard for the public good … ” Lindsay squeaked into a second term without the backing of his party.

But amid all that tumult, Lindsay kept plugging away at his improbable vision of a more civilized city. He learned to use a set of wonky tools that at first seemed abstract and obscure but defined the course of future growth. His planners turned the zoning code from an ungainly set of prohibitions into a nimble instrument. New rules halted the rush to tear down Times Square’s old theaters and promoted the construction of new ones. In 1968, he blocked a proposal to top the freshly landmarked Grand Central Terminal with a massive tower, and compensated the owners by offering the transfer of air rights to adjacent lots. The deal even withstood a Supreme Court challenge.

Until the mid-sixties, the division of labor between the public and private sectors was clear: The authorities built infrastructure and housing projects; developers replaced the dusty and old (never mind its architectural value) with the profitable and new. Lindsay gave muscle to the fledgling landmarks law and demonstrated that the city could wangle developers into contributing to the common good.

In some ways, Bloomberg is the anti-Lindsay. Lindsay decentralized the school system; Bloomberg brought it back under mayoral control. And it’s hard to imagine Mayor Mike wading into a throng of black protesters in Canarsie and getting hoisted on their shoulders, as Lindsay was. But an exhibit at the Museum of the City of New York, “America’s Mayor: John V. Lindsay and the Reinvention of New York,” makes it clear that the current mayor has expanded on Lindsay’s uncredited legacy. Bloomberg, too, has discovered the joys of zoning. His planning commissioner, Amanda Burden, influences public design on every level, from waterfront benches to the disposition of megatowers. And just as Lindsay saved Grand Central, Bloomberg preserved the High Line in part by shifting air rights down the block.

At a time when many urban dwellers considered the city’s problems intractable—and fled to the suburbs—Lindsay expressed a belief that a competent, innovative bureaucracy could reverse the decline. During his reelection campaign, he called the mayoralty “the second hardest job in America,” which was his way of saying that running—even reinventing—New York was not a hopeless task. A couple of decades later, it turned out he was right all along.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.