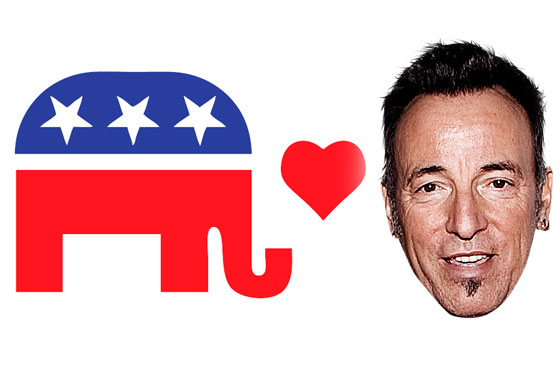

What is it with conservatives and Bruce Springsteen? The Boss is, after all, a declared fan of, and maybe even heir to, Woody Guthrie, who stamped this machine kills fascists on his Gibson Southern Jumbo. Yet Republicans are always trying to claim him as one of their own. Last week, Christopher J. Christie, New Jersey’s Republican governor-elect—a Spring¬steen fanatic who’s been to 122 of his live shows—asked him to play at his inauguration. Springsteen’s demurral was polite (he “doesn’t want to get involved in state politics,” according to Christie’s brother), but as soon as he declined, he endorsed the right to same-sex marry in the State of New Jersey—a right Christie steadfastly opposes. Springsteen’s sympathies are antiwar, environmentalist, and, as we now know, pro–gay rights; his enthusiastic support has been thrown behind the past two Democratic presidential candidates, and very pointedly against their opponents. Nonetheless, columnist David Brooks (who is a conservative in the true sense, if not always in a political one these days) recently wrote about the emotional tutelage he’s received courtesy of “Springsteen’s universe,” where “life’s ‘losers’ always retain their dignity. Their choices have immense moral consequences, and are seen on an epic and anthemic scale.”

Such ardor has a history. In 1984, George F. Will, in a bow tie and double-breasted blazer, his ears plugged with cotton, attended a Springsteen show. “I have not got a clue about Springsteen’s politics,” wrote a swoony Will, before declaring them like his: “He is no whiner, and the recitation of closed factories and other problems always seems punctuated by a grand, cheerful affirmation: ‘Born in the U.S.A.!’ ” That same year, President Reagan, visiting Jersey, declared, “America’s future rests in a thousand dreams inside your hearts; it rests in the message of hope in songs so many young Americans admire: New Jersey’s own Bruce Springsteen.”

Springsteen is white, male, rich, patriotic, and buff. His songs deploy imagery commonly used to sell soft drinks and Republican candidates—a stock Americana of family, farmscapes, country fairs, and, of course, cars as an Everyman deliverance from the mundane. Compassion and social hope are also indispensable to the brand, but easily obscured by the raw motive force by which his music makes white middle-aged men want to be Bruce Springsteen. That Bruuuce is a lefty can inspire calamitous identity confusion in someone whose second-most-intense passion is the elimination of the capital-gains tax. To regain composure, conservatives transform Springsteen from heir to Steinbeck and Guthrie into Horatio Alger. They insist on hearing the songs as vignettes of individual stoicism or uplift and not as protests, say, against a system of free enterprise run amok.

People are at liberty to set their jaws in the white man’s overbite and get down to whatever’s in their iPod. But some sizable portion of Springsteen’s audience is undoubtedly like Christie, unable to allow themselves to really believe that the songs, and the man, stand for something different from what they do. For his part, Springsteen could have sucked it up, delivered to his audience nondenominational feelings of rock-and-roll exhilaration. But search in Springsteen for signs of hypocrisy, limousine liberalism, naïveté, or dupery, and you find only an as-advertised man of simple good conscience. And for that, everyone, no matter their politics, can believe in him.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.