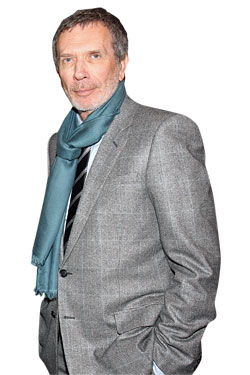

“The most wonderful time to be in the art world was in the sixties, because it wasn’t a business—there was no business of doing art,” says Arne Glimcher, the founder and chairman of the Pace Gallery, which these days is a very big business.

But also an exquisitely storied one. Glimcher founded the gallery in Boston in 1960 at the age of 22 (and relocated to New York three years later). On September 17, Pace will open “50 Years,” an exhibition that will fill all four of its New York showrooms, including a new branch on West 25th Street. Glimcher, who usually works at the gallery’s 57th Street outpost, is in Chelsea to make sure everything has been executed according to his meticulous specifications (a massive Robert Mangold canvas needs to be moved ten inches or so to the left). There are some 175 works (Giacometti, Picasso, de Kooning, Rothko, Pollock, Warhol, Lichtenstein, Nevelson) that were once shown or sold at Pace.

“It looks like the stack goes up forever if you come close,” his 10-year-old grandson Matthew says, poking his head into a Donald Judd sculpture. Later he takes off his loafers and gently tiptoes across Lucas Samaras’s Mirrored Room.

Glimcher started out as a painter but decided he just wasn’t good enough. “I have always been obsessed with excellence, and I was not going to be the most excellent artist in the world.” He turned to art history instead. He had aspirations of one day directing the Museum of Modern Art, but when his father, a cattle rancher from Minnesota named Pace, died, he decided to go into business. With the support of his mother, the help of his wife (art historian Milly Glimcher), and a $2,400 loan from his brother, Glimcher opened the gallery.

When he moved to New York in 1963, he took some risks: The gallery covered Louise Nevelson’s $20,000 debt to dealer Sidney Janis in exchange for exclusive New York representation, invested in difficult and expensive installations, and exhibited hard-to-digest California Minimalism, and it won the loyalty of a hot young painter named Chuck Close.

In 1980, Glimcher became the first dealer to sell the work of a living artist for over a million dollars with Jasper Johns’s Three Flags, which is on loan for “50 Years.” After the sale, “I got this great letter from Jasper,” Glimcher recalls with a laugh. “It said something like, ‘$1 million is a staggering figure. But let’s not forget that it has nothing to do with art.’ ”

His driver is waiting outside for us in a hybrid Mercedes to take us two blocks to lunch at Bottino. Over salmon, he talks of how the recession’s art-world correction “didn’t really happen.” Prices are still exorbitant, he says, speculators are still rampant, and artists are still manufacturing on deadline for their wait lists. “People see owning a gallery as a way to get rich. I never thought that I could get rich in the art world. I wanted a life in art. I wanted to live with artists. I wanted to make beautiful shows.”

In April, Pace and its longtime partner gallery, Wildenstein & Company, split, and PaceWildenstein became the Pace Gallery once again. Glimcher’s son Marc is taking over day-to-day operations at Pace, while Glimcher’s focusing more on China. He’s traveling there six times a year now. Pace has a Beijing outpost and is considering opening one in Shanghai.

“You feel the urgency in China,” he goes on. “With the Cultural Revolution having completely destroyed everything, they have this clean slate. The collectors there are more as they were here in the sixties. You have this new middle class that is fascinated with its own artists and supporting its own artists … In some ways, I think the American narrative is dead, whereas the Chinese narrative is just beginning.” His narrative is now on display. “It feels good, but it feels weird,” he says of the show. “Like seeing your life laid out before you.”

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.