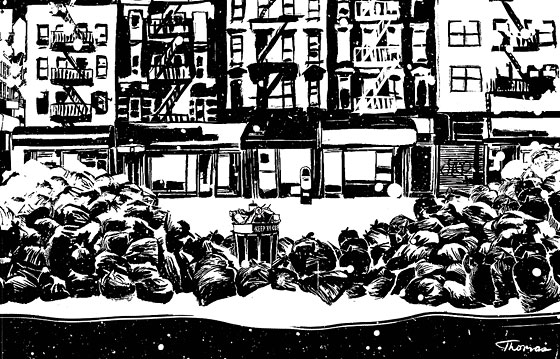

On the best of days, garbage is a nuisance, but when it lingers longer than normal on city streets, there are many reasons to grumble. Berms of black plastic bags do nothing to enhance neighborhood aesthetics, and the whole fetid collection becomes a five-star dining experience for rats. Yet that’s nothing compared with a deeper, more subtle dread that trash can provoke.

It’s not that garbage-bag gatherings themselves are unusual in New York. Starting in the early-nineteenth century, city planning (such as it was) left us with few alleys or other out-of-sight places to stash trash on collection day. And so we have to leave our refuse out for all the world to see, to the surprise of a lot of newcomers. New York functions as well as it does in part because, no matter how often we besmirch our sidewalks with sacks of rubbish, it’s all picked up with punctual efficiency.

In fact, it is one of the ironic privileges of modern life that we don’t give our trash much thought. We put it on the curb and go about our lives; when we look again, it’s gone. It’s not for nothing that solid-waste managers call it a “stream.” Like their aqueous counterparts, waste streams flow continuously—nearly 60,000 tons a week in New York, and that’s just for household trash. That flow is stopped very rarely, and then only because of an extraordinary disruption, so any change is unsettling. A city adorned in garbage is a city out of its proper alignment with the universe.

When trash piles up, it shows us one of the otherwise hidden costs of speed. New Yorkers, like many urbanites, require what I call an average necessary quotidian velocity. More plainly, we like to move fast. But a breakneck pace can only be maintained because so much of our material world is disposable: If that coffee cup or plastic bag or hand towel required care, it would encumber me and thus slow me down. Such choices, of course, contribute to the ever-rising volume of our castoffs, an unhappy fact that we mostly ignore. The post-blizzard piles of trash, with their in-your-face visual rudeness, have been vivid reminders that garbage is the constant and necessary dark side of our everyday conveniences.

And then there are the secrets that lie within our trash. One weirdly effective way to embarrass someone is to excavate and analyze the contents of his garbage can. I’ve seen this firsthand, when I required my students in an anthropology seminar to save and then bring to class everything they normally would have thrown away during a single 48-hour period. Though they were enthusiastic about the exercise, they were downright inhibited when it was time to do an archaeology of their refuse. Even if our telltale remnants are usually not held up to such scrutiny, we’d still like them all to disappear as fast as possible, please.

We feel these things because garbage points to one of our most profound fears. The raw fact of household waste, particularly the way we make it in this time and place, is proof that whatever comes into our home as “goods” sooner or later goes out as “bads.” It’s a reminder that everything is temporary. Everything. Not just your stuff. Yourself, too. No wonder we want it out of our sight.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.