When Amy Chua’s Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother was excerpted in The Wall Street Journal, jaws hit the ground on architect-designed playgrounds nationwide. Proudly, she told of depriving her daughters of play dates and sleepovers so they could drill endlessly on the piano and violin; once she wouldn’t let her younger girl pee until she had mastered a piece. She’d trashed a birthday card the same daughter—who was 4 at the time—had made for her, complaining it didn’t show enough effort. And when her older daughter earned only the second-best grade on a math quiz, Chua made her take twenty practice tests—every night for a week. Intended to be funny, instead the piece outraged. Most readers only heard bragging about the superiority of her ironfisted parenting. That her girls had become musical prodigies, one of them doing a recital at Carnegie Hall, didn’t justify stealing their childhood.

To top it off, Chua had played the race card. Despite being raised in the American Midwest, she’d wrapped herself in the cloak of Chinese tradition: If you don’t like this approach, don’t criticize. Respect our culture, it works for us. Yet criticize so many did. The Mommy Wars had just gone international.

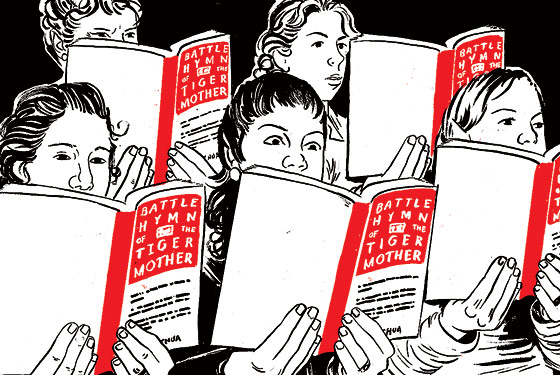

But here’s a question: If everyone hates this lady, why is her book selling so incredibly well? Battle Hymn of the Tiger Mother has been a blockbuster, ranking in Amazon’s top five last week. Parents have had no trouble laying down $25 and sacrificing five hours of late-night television to soak up Chua’s story. And this speaks to a dirty secret, something unmentioned in the official public backlash: American mothers and fathers are dying for permission to be a little tougher on their kids. Every time little Finn recognizes a letter, kicks a ball, or bangs on the keyboard, his parents have been conditioned to robotically chime, “Good job!”—the fear has been that no child can survive the competition and endless comparisons of today’s upper-class upbringing without these pick-me-ups. But parents wind up exhausted by all the cheerleading, much of which is empty pantomime.

“What Chinese parents understand is that nothing is fun until you’re good at it,” writes Chua. The point is, kids don’t want to suck at sports, they don’t like being lost in math class, and they don’t enjoy the distorted aural contours emanating from their instruments. The cheering is nice, but they’d prefer that someone actually teach them how to improve.

Of course, the lessons Chua is imparting are undercut by the fact that her style of parenting is no longer the norm in China. For the past ten years, parents there have rapidly Westernized, and studies show that modern Chinese moms are now as warm and accepting of their children as their American counterparts, if not more so. Those scary-high math scores in Shanghai are being posted by China’s “Little Emperors”: little boys and girls with no siblings, dropped off at school in luxury cars, cuddled and given every chance to get ahead by their loving, overly involved parents.

But that hardly matters. The American parents who are reading the Tiger Mother’s tale aren’t looking to copy Chua’s cruel coldness; they’re smart enough to edit that out when they try this at home. It’s her daughters’ success they’re after. These parents have long wrestled with an internal conflict, coddling their kids’ egos to protect their psyches, even as they’ve suspected that that approach might stunt their achievement. Tiger Mother resolves that contradiction. What it teaches is that kids might actually want to get ahead just as much as their moms and dads want them to—a message that relieves the guilt of achievement-driven parents, freeing them to let up on the self-esteem boosting and concentrate on the results. Chua may be too extreme to adopt as a role model, but that doesn’t mean these parents won’t turn to her book as their guide.