Sports fans are living in a golden age of crippling labor disputes, if “golden” can ever be applied to such unpleasantness. In the past fourteen months, the NFL has had two of them, the most recent of which, the referee lockout, arguably jeopardized the safety of players—the league’s obvious sore spot—to save a few bucks. Last season, the NBA truncated its schedule by sixteen games when owners locked out the players in a fight over revenue distribution; last week, the NHL canceled its preseason games—including what would have been the first sporting event at Barclays Center—and regular-season games through October 24. The people who follow these sports set their calendars to them, but they’re learning that they can’t count on the leagues to deliver on time.

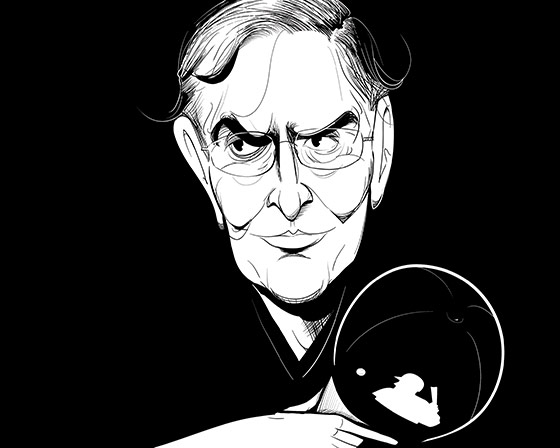

Then there’s Major League Baseball. After producing the cruelest labor dispute of all—in 1994, the year the league had to cancel the World Series—it has gone nineteen seasons without a union-owners standoff, and, thank you, Raul Ibanez, is now treating fans to another stirring postseason. The key to its unmatched stability lies, improbably, at the very top, in 78-year-old commissioner Bud Selig. This would be the same Selig who presided over the 1994 shutdown, but who has since outperformed his peers in smoothing over the fractiousness that is now built into the sports business.

For years, pro teams were owned by men (and women, but mostly men) who’d made their fortunes in other endeavors and treated having a franchise as a sort of lifetime-achievement award. Making money was preferable to not making money, but profit wasn’t the primary objective: Vanity and ego-gratification were; winning games was also nice, as it fostered the first two. This was the age of your Ted Turners, your Marge Schotts, your Gene Autrys. And it is not the age we’re in today. Today, sports teams are often owned by consortiums or descendants of past owners, for whom, in many cases, they are the only source of real income. Cities fork over the funds for shiny new stadiums that bolster owners’ bottom lines, while the owners look to wring maximum returns. Which has led, inevitably, to harder lines at the negotiating table.

Meanwhile, in three of the leagues, the commissioner’s office has gone from impartial mediator between players and owners to public representative of the latter; the independent arbiter, a role embodied by Pete Rozelle and Peter Ueberroth, has been replaced by a CEO-answering-to-shareholders model. This problem is compounded by the fact that, in those same leagues, the shareholders are revolting. NBA commissioner David Stern, NHL commissioner Gary Bettman, and NFL commissioner Roger Goodell have had decreasing success getting their owners onto the same page; the labor woes have been a direct result of hard-liners’ forcing strident stances.

This is where Selig has thrived. Formerly a small-market owner himself with the Milwaukee Brewers, he has extra credibility with current owners, many of whose team purchases he personally approved. (There’s a sense that only “Bud’s guys” get franchises. Mark Cuban, not a Bud guy, was famously denied.) Agreements he helped hammer out distribute the spoils from the league’s wildly profitable online arm evenly among teams, money that, when added to the league’s painstakingly preserved revenue-sharing system, helps keep less-flush teams in line. Once considered a lackey of MLB owners, Selig has become their shepherd. The other commissioners are learning the hard way what happens when their herd runs amok.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.