Egomania is a requirement in politics. Ed Koch turned the condition into an art form. He was far more interesting, and more complicated, than the common narcissist. His towering self-confidence was central to his triumphs and failures as mayor, because it enabled Koch to do what ever he thought necessary to save the city, whether that meant clowning for the cameras or betraying allies or berating political bullies. He was smart and funny and tough. But Koch’s real power was that he poured his selfishness into a wholly unselfish devotion to his city.

He started out as a reformer with conventionally leftish views: against the Vietnam War, in favor of civil rights. But Koch understood, and agreed with, the growing centrist Democratic revulsion against government bloat, drugs, and crime. He had no time for victimology. As the city careered toward chaos during Abe Beame’s term at City Hall, Koch saw his chance: Dubbing himself “a liberal with sanity,” he ran for mayor in 1977 and beat Mario Cuomo, on the strength of his personality and by appealing to the white outer-borough ethnic voters who were angry and scared. Koch had core beliefs and principles, but the ’77 campaign also established a template: To win, the former reformer was willing to embrace both corrupt Brooklyn political boss Meade Esposito and beauty queen Bess Myerson, the latter in the service of a fake romance concocted by his campaign wizard, David Garth.

It’s difficult, in these mild times, to fully appreciate how deeply New York was Crazytown in the Koch era: Blackouts! Garbage strikes! Transit strikes! Bankruptcy! Crack! Parking-meter scandals! His genius was in both stoking and taming the nuttiness, often by making the debate about him. Years later, telling me about those days, Koch seemed on the verge of self-doubt: “When I was elected, I said to myself, Can I do this? Seven people ran, and some of them were extraordinarily capable.” But the moment of near humility passed very quickly, as Koch continued: “And I said to myself, But the people picked me!”

Koch’s self-regard boosted the city’s spirits in the late seventies and allowed him to stand up to the bankers and labor unions who were squeezing the city’s finances. It also steeled him to make unsentimental choices. “The people who had to sacrifice the most were the poorest,” Koch told me. “Because that’s where the city budget goes. Two thirds of the budget. All the left-wingers, the Village Voice people, yelled, ‘He’s balancing the budget on the backs of the poor!’ ” He shrugged. “And I said, ‘Who do we spend the budget on?’ ”

Thanks to a second-term economic boom, Koch did spend money supporting the city’s middle and lower classes—most spectacularly by creating more than 200,000 units of subsidized housing. Eventually, though, his confidence metastasized into arrogance, with tragic costs: Koch’s nasty reaction to criticism from AIDS activists weakened the city’s response to the fatal epidemic. And his long-running hostility toward black leaders, coupled with the murder of teenager Yusuf Hawkins, helped Koch lose the 1989 election.

Three terms of Koch, however, were more than enough to shape the city’s politics, perhaps permanently. He was a bridge from boss-controlled elections to the media-centric ones we know today, and from Jewish-Catholic working-class-neighborhood New York to the current artisanal/real-estate industrial complex. The scars of seventies New York are invoked every campaign season, with each candidate promising he or she won’t let us slide back to those bad old days. The crucially effective parts of Koch’s tough-love response to New York’s troubles, particularly his never-back-down-to-criticism attitude, became, for better and worse, fundamental pages in the playbooks of Rudy Giuliani and Mike Bloomberg. Koch rescued the city in his first term and nearly split it in his third. He will forever be an object lesson in the cold-blooded calculations necessary to thrive in New York politics, and of the joys and dangers of personality-driven politics. When I asked him how he could endorse Andrew Cuomo for governor in 2010, after years of bitterly blaming the Cuomos for those homophobic 1977 campaign posters, Koch smiled. “A primary’s like a civil war!” he said. “There’s nothing like it. But it’s ov-ah!”

And besides: The good guy—him—won. Koch’s overweening ego made being mayor all about him—but the magic was that it also convinced enough voters that he was doing it all for them. Sometimes New Yorkers loved him, sometimes we hated him—and for a long time we needed him, almost as much as he needed us.

See More

• Mario Cuomo on His Old Foe

• Hizzoner’s Many Roles and Magazine Clippings

• The Legacy of the Koch Building Boom

• His Love for a Broken City That Loved Him Back

• Maer Roshan on His Dinners With Koch

• New York’s Last Mayor From Main Street

• Koch and the AIDS Crisis: His Greatest Failure

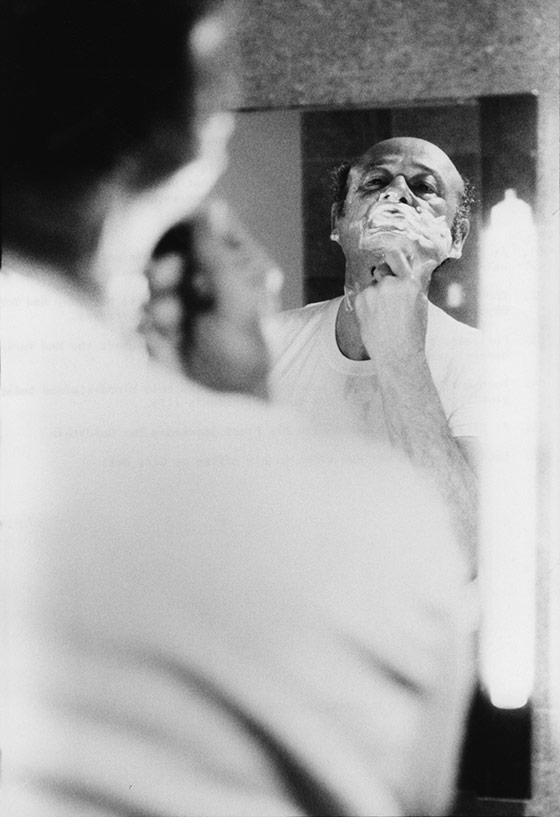

• A Life in Pictures

• Complete Coverage on Daily Intelligencer

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.