“You guys think this is a joke. This is not a joke.” Dennis Rodman is seated at the dais in a conference room at the Soho Grand Hotel behind a bronze bust of himself. Next to him is a smartly dressed Irish bookmaker named Paddy Power. On Power’s other side is Daniel Pinkston, a North Korea expert with the International Crisis Group, a pro-NATO think tank that focuses on war and violent conflict. Before them are scads of reporters and cameras. Despite Rodman’s admonishment, a TV personality from Fox Sports wearing a shirt that says I

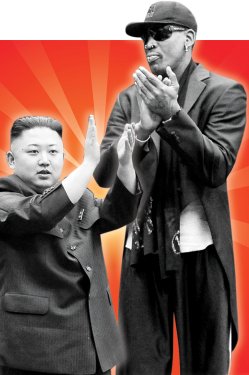

Rodman was there to make “big announcements” about his recent trip to North Korea as the guest of Kim Jong Un, his second in a year. And big announcements he delivered. During his seaside vacation with the Supreme Leader’s family, Rodman cut a deal not only to stage a series of exhibition basketball games in North Korea with ex–NBA stars but also to train the North Korean national team for the upcoming Olympics. He even invited Kim to a Knicks game.

Should any one of these things actually happen, it would be a historic event. No North Korean leader has ever visited the United States. Just this past spring, Kim threatened a nuclear attack on U.S. bases.

“I’m pretty important now, right?” Rodman asks. “Call me, Obama. I’ve got the inside track.” He’s beating his chest, but he’s also kind of right. This most unserious man, who holds a celebrity-wrestling title and three Razzies alongside his five NBA-championship rings, now holds the keys to the Hermit Kingdom. This is our guy in Pyongyang.

Rodman’s first dive into international diplomacy came last fall, when the media company Vice invited him to shoot an episode for its new HBO series. Vice reporters had visited the country in 2008 for an online series in which they exposed North Korean labor camps in Siberia. The regime wasn’t thrilled, so to win them over for a second trip, Vice suggested bringing in the Harlem Globetrotters for some goodwill games. The North Koreans seemed unmoved, so they offered to bring a former member of the Chicago Bulls’ championship squads, an idea inspired by the revelation during Vice’s first trip that one of Kim Jong Il’s most prized possessions had been a Michael Jordan–signed basketball presented to him by then–Secretary of State Madeleine Albright.

When Vice approached him, Rodman’s only recent public appearances had been the occasional headline for getting tossed from a restaurant for drunken obnoxiousness. During the trip, Kim and Rodman sat side by side while the Globetrotters and North Koreans played together in mixed squads. Kim chatted up Rodman at dinner after the game while guests performed karaoke. The Marshal was so smitten he invited Rodman to come back and visit.

Once home, Rodman told reporters, “Guess what, I love him,” and called Kim his “friend for life.” When he was then accused of tacitly supporting an oppressive regime, instead of backing off he doubled down on his one-of-a-kind relationship. He suddenly found himself the only conduit the outside world had to a rogue nuclear power.

The press surrounding the trip caught the attention of the Irish online bookmaking operation Paddy Power (the name of the company as well as of the company’s spokesperson), which signed Rodman to promote its betting offerings on the selection of the new pope. Rodman flew to Rome. It was in Vatican Square that he first pitched his idea of a more extended “basketball diplomacy” to Paddy.

When news broke that Rodman would be going back to North Korea, humanitarian groups saw it as an opportunity to press for reform. An op-ed in the Seattle Times asked Rodman to advocate for the release of Kenneth Bae, an American citizen serving a fifteen-year sentence for “hostile acts”—he allegedly possessed footage of malnourished children. Former U.N. ambassador Bill Richardson and Google co-founder Eric Schmidt had traveled to North Korea with a letter from Bae’s family, but neither was granted an audience with Rodman’s friend for life. The U.S. human-rights envoy to North Korea, Robert King, had been scheduled to visit Pyongyang just days before Rodman, but that invitation was rescinded after the U.S. participated in military drills with South Korea. Now, the op-ed argued, it was time for the Worm to come off the bench. Rodman tweeted that he’d read the article and agreed to help.

But seated in front of the gathered press, Rodman quickly gets defensive. “What about what we’re doing over here? What about Guanamatana?” he asks. “Why don’t we go over there and check that out? Ask Obama about that.”

The flack from Paddy Power tries to deflect, but Rodman won’t relent. “I’m not going there to be a politician. I’m going there to be his friend.” As the questioning continued, it becomes pretty clear that Bae didn’t come up in Rodman’s conversations with the Supreme Leader, and the Worm looks like an increasingly poor choice for a U.S. emissary.

And yet at the end of the dais sits Daniel Pinkston, the North Korea expert, looking stone-faced and serious as a heart attack. When Power decided to back Rodman’s exhibition games, the bookie engaged Pinkston, who works for the International Crisis Group, to help ensure that the event was put on “in as responsible and sensible a way as possible,” according to Power.* Pinkston added visits to schools and sports clubs to the itinerary. “If you’re a kid and you see these stars and they play basketball with you, that is an experience that a kid will remember for the rest of his life,” explains Pinkston. “It undermines the narrative that describes Americans as evil and wicked and set to invade them at a moment’s notice.”

Pinkston sees cultural diplomacy as essential to bringing about reform, even if the cultural diplomat is someone as strange as Dennis Rodman. And he may have a point. The U.S. table-tennis team’s 1971 visit to China—the first time Americans had visited Beijing since 1949—is often credited with paving the way for President Nixon’s trip the next year.

“Dennis is the perfect person for this. He couldn’t be manipulated by the regime even if they wanted to,” says Pinkston. What better challenge to the most conformist, monolithic society on the planet than a six-foot-seven cross-dressing, cursing, boozing African-American covered in tattoos and facial piercings? Besides, Pinkston argues, Rodman isn’t actually a diplomat, either implicitly or officially. “Sitting down in a stately room with private citizen Hillary Clinton creates a kind of status. Sitting down with Dennis Rodman doesn’t achieve that.” But even if Rodman is just bro-ing out, it’s not without its value.

Rodman seems to get this. “I’m not trying to go over there and rescue someone,” he says. “I’m trying to open doors. And once those doors are open, maybe things will be different.”

Still, the Worm can’t seem to comprehend how he got himself into this situation. “Why did Dennis Rodman have to come and break this ground?” he ponders aloud from the dais. “Why me?”

*This article has been corrected to show that Paddy Power did not hire the International Crisis Group.