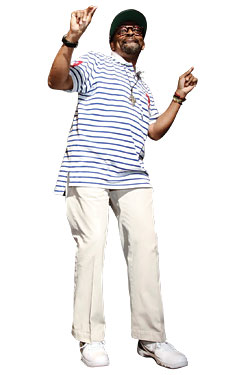

There’s a ripple coming down the pavement in Bed-Stuy. Faces turn, then bodies, twisting midstride in the street. “Holy shit!” someone says. The black SUV with tinted windows pulls over near the corner of Stuyvesant and Lexington Avenues, depositing a familiar five-foot-six disruption to this quiet Brooklyn block’s space-time continuum. “Spike Lee! Shit!” the teenager says again, conferring with his friend as to whether they should approach or play it cool, even though it’s kind of impossible to play it cool when you’re hyperventilating. Lee doesn’t look their way as he lopes across the road in white sneakers, a white shirt, and his usual Yankees cap. Even while grinning, Lee manages to exude the manner of an incoming fastball, just inches away from buckling you to your knees. The man does not suffer fools. The teenagers keep moving.

“Twenty years went fast, son!” shouts a far less intimidated Steve Williams, 49, who’s stuck on his stoop all day, thanks to a torn tendon that has put his entire left leg in a cast. That was when Lee took over the block for two months, directing Do the Right Thing (which he just remastered for DVD). “It looks better!” says Lee. “Houses used to be boarded up.” He’s gesturing to one of several crack dens his crew took over and cleaned up for the movie.

“That’s where Sal’s Famous was,” Lee says, pointing to the grassy lot where they’d built the pizzeria set. “And that’s where the Korean fruit stand was,” he says, pointing to the still-unbuilt land where the fake corner store once stood. But mostly they shot in and around real buildings. No. 176 housed the radio station, where Samuel L. Jackson hid out in the set’s only air-conditioned room as D.J. Mister Señor Love Daddy. No. 169 was where Mother Sister, played by Ruby Dee, leaned out her window and yelled at Da Mayor, Dee’s real-life husband Ossie Davis, who lived at No. 178. On the corner, the faint outline of the BED-STUY—DO OR DIE mural painted for the movie clings to an old brick wall partially obscured by a newish apartment building. The mural of Bed-Stuy’s own Mike Tyson that used to loom over Sal’s is gone. It faded away naturally about three years ago, then the landlord painted over it.

Even after Mookie helped burn it down in the movie’s riot scene, the set for Sal’s was such an improvement, Williams remembers, that the residents didn’t want it carted away. No such luck. “Here’s the reality,” Lee says. “Film crews come in. They shoot, then they leave. The last day of filming, we made a brass plaque saying, ON THESE DATES DO THE RIGHT THING WAS SHOT HERE. And somebody dug it up. It was gone! Didn’t last a week!”

Lee is now sitting on one of the bollards protecting the fire hydrant in front of Williams’s apartment. This is “the hydrant,” Lee announces. The one used in the movie to cool off the block’s residents and then to douse some prick Italian’s classic car. “Remember that scene? Let me show you.” Excited, Lee cups his hands and demonstrates. “So you get a beer can or a soup can. You gotta scrape the can on both sides on the sidewalk and then it comes off, the top and the bottom, and then you put it over the water, and it shoots out. That’s how we kept cool. And we don’t call them fire hydrants. We call them Johnny pumps. Somebody always had a wrench for opening the hydrant. And then the cops come and everybody would run.”

Today, Edward “Bernard” Weston, a 75-year-old retired construction worker, is watching the street from Ruby Dee’s place; Lee asks him to come down and help jog his memory. At the time, Weston lived in the building beside Mother Sister’s, until he got evicted so the landlord could renovate. He moved next door and has been there ever since. What he remembers most about the filming, he says, was feeling trapped. “If you were out of the block, they wouldn’t let you back on the block until they finished filming.” Other than that, “I wasn’t paying no strict attention to it because I wasn’t making no money from it.”

It’s time to go. Williams watches Lee pull away in his SUV. “He’s Hollywood,” Williams says. “I don’t think he could make a film like Do the Right Thing or Bamboozled today. I’m not knocking him or anything, but he’s gained about twenty pounds. He was tiny! I remember shaking his hand. I thought I was going to break him.” Williams says he thinks it would be a nice thing for the neighborhood if Lee replaced that plaque. “He can make another one. He can afford it.”

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.