Right here,” says the artist James Rosenquist, pointing above the Palace Theatre on the corner of Seventh Avenue and 47th Street, “there was one big sign with Harry Belafonte’s face on it, and they pulled me up from the street with a chair to touch up his nose, because they scratched it putting it up.”

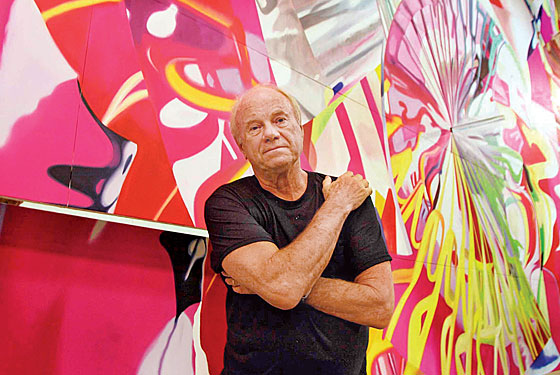

After reading his just-published rich, vivid memoir, Painting Below Zero: Notes on a Life in Art, I meet him in Times Square so we can look at the 360-degree orgy of digital-age signage. But Rosenquist, 76, in jeans and black work boots, affably blunt and salty in a way that still bespeaks his Depression-era North Dakota upbringing, keeps looking past the flashing LEDs to the ghosts of the billboards he worked on.

He pivots, points up again. “Between 47th and 48th was a club called the Latin Quarter. On top of the roof, I painted Smokey the Bear and JOIN THE NAVY signs.” He points down the street corner. “I spilled a goddamn gallon of purple paint right on the sidewalk at noon. It went off like a bomb—it just exploded!”

Not long after that, Rosenquist’s career exploded. His innovation, much like Andy Warhol’s, was to bring the imagery—and the scale—of the billboards he’d been painting into the gallery. The work was gorgeous and sensual and ironic simultaneously, a bright, surreal jumble, much like Times Square itself. Rosenquist’s epic, humongous 1965 painting F-111—it’s 86 feet long—captured as no one else had the fantastic, horrifying American cornucopia of gleaming war machines and canned spaghetti and mushroom clouds and Firestone tires, all weirdly harmonized and of a piece. He’s still working in that jangly genre—if anything, his paintings are more vivid and surreal than ever. He’s also as influential as he ever was. It’s hard to look at Richard Prince’s work, say, or Marilyn Minter’s, without seeing Rosenquist’s shadow.

Rosenquist is a wonderful raconteur—in his memoir and his person, the days of his youth are totally present. But he is not happy with the new Times Square. I point to a cluster of signage over the Palace: big, slick placards for the new movie Where the Wild Things Are and Broadway fare like West Side Story, Chicago, and South Pacific. “I don’t like any of them,” he sniffs. “They’re just cold photographs of stuff. What I did, it was the long-lost method of painting the Sistine Chapel. We’d have a small sketch and then square off the sketch and the building with chalk. You just drew it and mixed the paint and painted the goddamned thing.”

The new Times Square is bugging him. “It’s a little too much. I’m getting xenophobic.” Claustrophobic? “That’s right,” he says.

In search of the New York of his youth, he suggests we go to the Stage Deli to get a corned-beef sandwich and a soda pop, as he calls it. I tell Margarita, our chatty Peruvian waitress, that he’s a famous artist. She asks why no paintings of his are hanging here in the restaurant. “Darling,” he tells her, “if you go by Broadway and 65th, look at the Met Opera. There’s my painting, big, for the opera Tosca.” (His painting is a classic Rosenquist pop mash-up, complete with a gun barrel, a knife, a rose, and fragments of a fashion model’s sultry face.) So why not here, Margarita insists. “I don’t do that, I don’t put ’em in restaurants!” he says with a gruff smile.

Thumbing through his memoir at our table, we come across a photograph taken in the Odeon’s basement, of the gallerist Leo Castelli surrounded by his powerhouse stable—Rosenquist (he’s with Acquavella Galleries now), Rauschenberg, Ruscha, Kelly, Serra, Johns, Oldenburg, and more. The photo makes him sad, thinking about artist peers he’s outlived. “They’re not around, they’re dead,” he says. “D-E-D, dead. Roy [Lichtenstein], Andy, Dan Flavin, Don Judd. I hate it. You can’t call them up for a recipe anymore because no one answers.”

A recipe? “Yeah, for rabbit-skin glue,” he says, which is used to prep a canvas for oil paints.

Other things have been lost, too. In April, a massive forest fire destroyed his home and studios in Aripeka, on Florida’s Gulf Coast. (He and his wife, writer Mimi Thompson, have also long had a five-story home here on Chambers Street.) Rosenquist estimates he lost about $14 million in artwork and print archives; he’d never taken out insurance in order to avoid the large premiums. “There it is, zilch, nothing,” he says. “A total wipeout. What happens is, one becomes nonmaterialistic. I think of my actions every day, what seems to be important and what isn’t.”

Rosenquist is not sure how he’s going to spend the rest of the afternoon; maybe he’ll drop by the nearby Art Students League, where he first went when he moved to New York in 1955. I ask him about Mad Men, which he’s never seen. The smiley-happy Camelot-era ad images over its solemn, foreboding theme song evokes Rosenquist’s work, and the show’s characters are the same type of people who created the images that Rosenquist borrowed, to such powerful effect.

“I used to know Madison Avenue advertisers,” he says watching the sequence on my laptop. “I didn’t like ’em. Bunch of jerks. ‘Hey, man, what are you hipped on now, man? What’s the latest?’ Screw ’em.”

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.