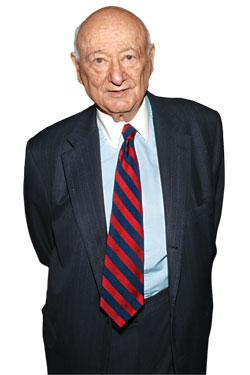

This could be my last hurrah,” says Ed Koch, the 85-year-old ex-mayor. He’s leading an octogenarian’s crusade against what’s wrong with the very political Establishment he’s been a part of for decades. In March, he created a political-action committee that will not only monitor the voting records of Albany legislators on good-government issues but also, he hopes, shame them into supporting a reform agenda. Koch’s PAC, called New York Uprising, is a clubhouse of sorts for boldface Brahmins and politicians at pasture, many of whom have been Koch’s enemies in the past, such as Mario Cuomo and Rudy Giuliani, about whom Koch wrote a book, Giuliani: Nasty Man.

Today Koch sits at his desk at Bryan Cave, the law and lobbying firm where he has been working since he left government two decades ago. He’s clutching a big plastic mug—a bucket almost—full of water. (“I drink water all day. They say it makes you thinner.”) The sun is beaming in through the windows and the air is still. On the walls are a pol’s typical shrine of honors and photos. (“This Jewish corner is of me, in Jerusalem. The intifada had started, and they threw a rock at me and hit me on the head. I was just gushing blood.”)

In chairs around Koch’s desk are two of the Uprising members: former congressman Herman Badillo and Alair Townsend, who was Koch’s budget director. On the couch is Mark Botnick, a former Bloomberg campaign aide who is running Uprising’s field operation and is now doing laps around the finger pad of his BlackBerry.

I ask each to describe Albany in a word. “Corrupt,” says Botnick.

“What’s the word? … I’m a little deaf,” Koch says.

“Corrupt,” Townsend says.

“I would use that or another word,” Koch says. “Slobs. When I first got involved with this, I said, ‘We’re going to throw the bums out, because the good aren’t good enough and the bad are evil.’ ” But his fellow PAC members had friends in Albany they wanted to keep. So he has a new, edited line to throw at reporters. “We’re going to give the good guys the backbone to stand up.” There’s a difference. “I don’t say anymore, ‘Throw the bums out.’ ”

But which bums was he referring to? “Well, we know there were three rats,” he says, meaning Democratic state senators Pedro Espada Jr., Ruben Diaz Sr., and Carl Kruger, who revolted last year. “I can easily substitute the term bum for rat.”

Mostly Uprising has focused on a technical issue: how party leaders create political districts. Now, whichever party is in power gets to gerrymander. Koch supports legislation that will create a nonpartisan committee that will draw up the districts.

Both parties’ candidates for governor—Andrew Cuomo and Rick Lazio—have signed the redistricting pledge. Koch shows me how it’s even in Cuomo’s campaign position book. “Here it is,” Koch says, reading: “Legislation, coupled with the recent effort by citizen groups, led by former mayor Ed Koch, illustrates that the time is ripe for action.”

“That’s pretty good,” Koch says, proudly. “It’s on page sixteen.”

But isn’t it the politician’s way to make promises he won’t keep?

“Oh, no, no,” Koch says, about the pledges Uprising has received. “It’s in writing. People say, ‘What if they don’t keep their promise?’ The answer is: I’m going to run around the state, and I hope others will run with me, yelling ‘Liar, liar, pants on fire.’ ”

“And he has a big mouth,” Townsend says.

Part of Koch’s problem is that the powerful State Assembly speaker Sheldon Silver didn’t sign—it’s unclear why Silver would want more Republicans to have a say in how districts are drawn—and beyond that, attempting to shame legislators into doing anything doesn’t always work. In his abbreviated term as governor, Eliot Spitzer threatened electeds with public tarring in their districts if they didn’t get into line. But the crusade never happened, Spitzer soon learned, because winning reforms in Albany is more about making allies and cutting deals than impressing editorial boards by belittling officeholders.

Koch says they’re not like Spitzer. “Eliot’s position was that he was the smartest person in any room, and he would not brook discussion. That’s not any of us.” Besides, “he had a screw loose. There’s no question. Whether it’s DNA or genes, I don’t know how you get a screw loose but that’s what he had. He was mad. M-A-D.”

After an hour and a half of talking almost continuously, Koch reaches for the mug and takes a gulp.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.