It’s a good thing Candice Bergen requested a quiet booth at Bar Centrale, the unmarked theater hangout, because the first thing she says, sidling into a booth, is barely a whisper. “I get worn out because I’m old,” she says, sighing, then gives a chuckle about one-twentieth as loud as the trademark cackle of her ballsy nineties alter ego, the fictional journalist Murphy Brown. A few minutes later, Bergen is drowned out by some perky blonde new arrivals, forced to indulge them with a good-natured shrug and a slow sip of her red-wine spritzer. “People complain about parts for women, people complain about getting old,” she says. “It’s a privilege to get old.”

At first, it seems the quiet self-deprecation might just be Method. Bergen plays heavily against her best-known type in the timely new Broadway revival Gore Vidal’s The Best Man, as a politician’s neglected wife. Though Alice Russell is variously described in the play as “chilly looking” and “not cozy, I’m afraid; not cozy at all,” Bergen injects the role with surprising vulnerability and diffidence. “I was following what Gore wrote,” Bergen tells me, “but I didn’t want to do another patrician, distant dame.”

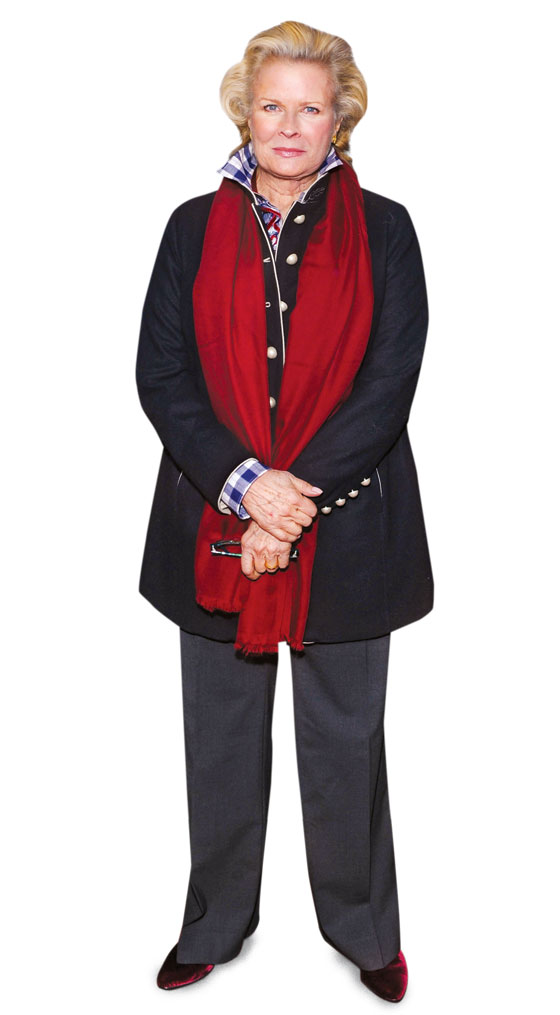

Born in Hollywood’s warm bosom, daughter of a world-renowned ventriloquist made famous, improbably, by the radio, Bergen spent decades trying to live up to her own pouty Swedish beauty in a string of stiff, earnest performances. “Her only flair is in her nostrils,” wrote Pauline Kael of her first role, in The Group. By the late eighties, though, she’d found her flair in the family trade: comedy. (It happened to be on television, which, she told Playboy at the time, “vulgarizes everything” and “rewards mediocrity.”) Now, at 65, she’s making what is essentially her theater debut (she did a quick replacement stint in Hurlyburly in 1984) alongside dramatic lifers James Earl Jones and Angela Lansbury. And she’s playing a faded, cheated-on would-be First Lady in an unbecoming silver pageboy, outshouted and overshadowed by a young minx against the backdrop of a brokered convention. It’s two parts Hillary Clinton, one part Barbara Bush, and more Candice Bergen than you’d expect. “The reality is that I don’t look like I used to look,” she says. “I just don’t care enough, and in a way it’s saved me.”

Bergen, who once turned down Don Hewitt’s offer of a job on 60 Minutes, is uncommonly candid with journalists, and here in the soft light, surrounded by fifties-style zebra stripes, she soon confesses the deeper source of her timidity. Rounder of face, grayer and wispier of hair, Bergen tells me that in the fall of 2006, she had a minor stroke. She denied it at the time and is reluctant to admit it today, because “I just don’t want it to be a liability.” She says she missed only two weeks of shooting on Boston Legal, the one-hour comedy on which she had a major role opposite John Larroquette (her candidate husband in The Best Man). Still, years later, “my memory is just—” she pauses. “It’s not quite the same.” Just five months ago, she says, she broke her pelvis while on a bike ride. “Wow,” she remembers thinking, “now I can fall and I’ll break.”

When producer Jeffrey Richards approached Bergen for the role, she hesitated. Broadway has long provided safe harbor for actresses aging out of Hollywood—while also exposing them to the nightly risk of irreversible errors. “My concern with theater was no retakes,” Bergen says. “I had no confidence in my memory, and I didn’t want to leave my husband”—the real-estate developer and philanthropist Marshall Rose—“who believes very much in a marriage where you’re present.” (Her first husband, the director Louis Malle, died of cancer in 1995.) Richards says he never had any doubts, and neither did Vidal, who said, “Jeffrey, she is right for this.” Bergen wasn’t so sure. “The closer it got, the more I thought, What have I done? I’m going to go out and make an asshole of myself! Now,” she says, “I am so grateful that I did it. Frankly, just not being a shambles onstage.”

Bergen has had an apartment in New York since age 19, but rarely has been tempted by the one dramatic genre in which the city dominates. Now she seems to be falling in love with theater’s ragtag charms. “People are united in this tiny, few-block area,” she says. “They’re all theater rats, and they don’t care about living well.”

One of her favorite rituals is something most theater rats consider a chore: the daily vocal warm-up. Short on time today, she leads us briskly from the bar to the Schoenfeld’s stage door, taking a shortcut through a busy parking garage. Within ten minutes, she’s onstage, stretching and yelping with a half-dozen actors. “Hello! Hello!” they shout in unison, James Earl Jones’s voice booming above the others but Bergen’s not far below. “Way oh way oh way! Mmmahh! Mmmahh! The lips, the teeth, the tip of the tongue!” The warm-up leader cracks an inaudible joke, and a seasoned cackle, soft but confident, cuts through the din.