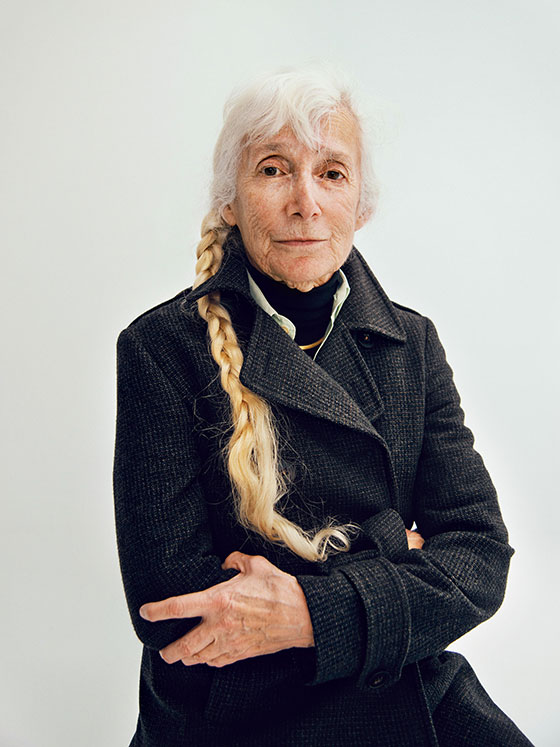

This is slowly panic-making,” Renata Adler says with a husky tremor. Out at her first cocktail party in months, the 74-year-old writer wears, as always, a single thick braid of hair, now gone a straw-tinged gray. “There’s Amanda Burden,” she says of the wellborn chair of the City Planning Commission. “I know Amanda. But see now, either you embrace somebody, thinking, Oh God, maybe they have no idea who I am, or it’s someone who’s my oldest friend and I forget. Should I go over?”

Instead, Adler heads for the acerbic media writer Michael Wolff, who is hosting us tonight in his surprisingly grand East Village apartment, and who profiled her kindly during “a troubled time”—thirteen years ago, when virtually no other writer in New York would have invited the former party fixture out for so much as a cup of coffee. Tonight’s occasion is a new book by the conspiracy-minded crime journalist Edward Jay Epstein, whom Adler met roughly 50 years ago “at the Moynihans’.” Lining Wolff’s walls are six photographs by Lori Nix that capture alarming dioramas: a plane crash, a lightning strike, a truck crashing through an icy pond. “Everything here is a kind of disaster,” Wolff helpfully explains.

It’s exactly the sort of line Adler would have pilfered for her jagged, episodic 1976 novel, Speedboat, which doubled as a primer on cutthroat literary life in New York. Long out of print, Speedboat will be reissued this week along with her second novel, Pitch Dark, exposing a new generation to Ur-texts of urban angst. “I often meet people who do not like me or each other,” says Speedboat’s narrator, Jen Fain. “It doesn’t always matter. I keep on smiling, talking … My dislike has no consequences. It accrues only in my mind—like preserves on a shelf or guns zeroing in, and never firing.”

That twitchy narrator sounds like a more assertive Joan Didion, and not so long ago Adler seemed destined to join Didion and Adler’s old mentor, Hannah Arendt, in the pantheon of women essayists. A 1983 cover story in this magazine even proclaimed Adler “A Writer for Our Time.” But a long attack on Pauline Kael (“piece by piece, line by line, and without interruption, worthless”) soured her relationship with The New Yorker, their mutual employer. Suing Vanity Fair for libel and writing a book-length indictment of CBS and Time didn’t endear her to fellow journalists. Then in 2000 she published a memoir, Gone: The Last Days of The New Yorker, in which she depicted the end of editor William Shawn’s reign as “a parody of King Lear.” The Times published eight mostly negative articles about Gone—“arguably nine,” Adler once wrote—and questioned the ethics of her “irritable little book” on its editorial page.

Adler considers herself the victim in the exchange. “People who I thought liked me really, really, really didn’t,” she says. “It brought back that kind of wallflower feeling, that boarding-school feeling.” Adler eventually repaired to Newtown, Connecticut, where she owned a former cider mill not far from her childhood home. She’s taken the train in today just for the party, and one of her missions is to scout a possible pied-à-terre. But she’s vague about this and other new prospects. “I think I’ve written this other novel, it seems,” she says. “It’s in the mail.”

Early in her hour-long lap of the room, a man in a houndstooth jacket introduces himself as Bartle Bull. “Oh my God, how are you, old friend? How long has it been?” he asks Adler. “Four thousand years,” she says, and compliments his tie—tiny white rhinoceroses on a field of blue. “This is very strange,” Adler says a moment later. “I’ve never met Bartle.” She spies a financier named Michael Pochna, a genuine old acquaintance if not exactly a friend, who reminds her of their time together in Sardinia, but who, she later tells me, “has never liked me, and I’ve never liked him either.”

Beside the shrimp cocktail, a handsome man in a too-rich-to-care turtleneck beams. “I’m Fred Smith—hi!” He and Adler, he explains, are “family friends of very, very long standing.” He’s a fan of Epstein’s journalism. “It’s only recently I’ve come to understand,” he says. “There really are conspiracies.” After he leaves, Wolff explains that “Fred Smith” is, in reality, Joe Rose, a real-estate developer and Burden’s predecessor.

“You ought to meet Henry Jarecki,” Adler says, sidling over to another old friend—a psychiatrist turned gold trader who’s now “very, very seriously rich.” She apologizes to Jarecki for having to leave early; tomorrow she’s due at a meeting of the Fairfield Hills Commission, where she’s one of eight members deciding what to do with a former mental institution in Newtown. (She’d turn it into a memorial park for the victims of Adam Lanza.) The other night, Adler says with an innocent shrug, she half-accidentally sent the commission “a deeply insulting, libelous e-mail” about certain allegedly corrupt Newtown players. “Renata,” Jarecki jokes, “is impersonating a little old lady.”

Having said the briefest hello to Burden—the kind of encounter she skewered in Speedboat: “approximations of longing to be together” enacted to secure “an exit from each other’s company in that instant”—we head for the coats. “Some woman came in and just started dumping everyone’s coats on the floor,” grumbles the man on coat duty. “It’s like, co-exist, darling!”

Adler’s face lights up. “Write that down. You have to use it,” she tells me. “It’s something I would long to use.”

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.