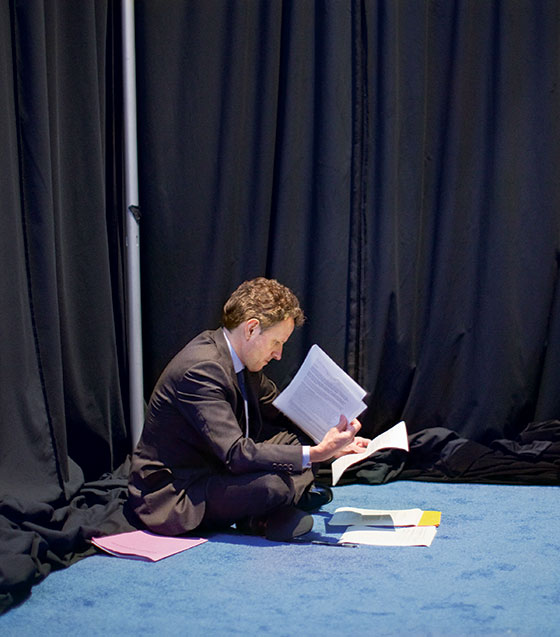

Like all larger-than-life characters, Tim Geithner is smaller in person. Not Tom Cruise small, but smaller than you would expect the most important figure in recent economic history to be. It’s strange to see him here, standing under a French flag at bistro Les Halles Downtown in the midst of the diminishing lunchtime crowd, waiting for the host and a pair of Secret Service agents to escort him to a table, instead of in his usual context: in front of an American flag delivering discouraging economic news, standing behind the president while he delivers discouraging economic news, or on Charlie Rose, trying to make the economic news sound less discouraging. “Is anyone eating?” he asks his chief of staff and an aide, who shake their heads and resume BlackBerrying. Geithner orders an espresso. I’m not sure why he chose this place; we could have met at the New York Federal Reserve, where he’s going to visit some of his old colleagues later. Perhaps he is trying to get a feel for civilian life again, this being his fourth-to-last day on the job. It’s sort of bold of him to show his face in the vicinity of Wall Street, whose denizens don’t have a lot of love for him, even as they’re said to have formed an unholy alliance with him. “I think he is the croniest of the crony capitalists,” one money manager told me earlier that day. “I despise everything he ever did.”

This kind of emotional reaction is par for the course when you are the Face of the Financial Crisis. “People project onto me all their deep hopes and fears and their anger,” Geithner says cheerily, “and that’s my job and I get to absorb that.”

For the past couple of weeks, as Geithner prepared to leave office, the intelligentsia has been busily parsing his legacy. While the overall consensus is that, as president of the New York Fed and then as Treasury secretary, he was successful in keeping the country from sliding into another Great Depression, there is still a goodly amount of anger and skepticism about how he did it. Going by the most recent polls, only 36 percent of the diners currently craning their necks toward the guy in the suit think he helped America out; 42 percent think he bungled things or bailed out Wall Street for nefarious purposes. The other 20 percent probably just think he is Lyle Lovett. For the subject of such controversy, Geithner is surprisingly Zen, describing himself as “at peace” with the decisions he made.

“You feel your plan worked …” is the way I choose to begin a question at some point.

“No, it’s not, like, a feeling,” he interrupts, with an appealingly dorky snort of laugher. “If you look at the record of this crisis response against other crisis responses, it looks very good against what we know about other countries’ experiences, and that is because of the choices we made. I don’t think that most people understand how bad it was or how bad it could have been. Maybe they didn’t think they had to be rescued. But in the history of finance ministries and Treasury departments, that’s the existential thing.”

Geithner has a lot of examples to draw upon. A lifelong practitioner of the art of defusing financial crises, he has spent his career hopping from one fiasco to the next—in Mexico, Asia, twice in Brazil—for the Treasury and the IMF. Which is why some argue that he should have seen one coming in the mid-aughts, when he took charge as president of the New York Fed, supervising many of the institutions that required federal assistance. When Obama first approached him about coming to Treasury in 2008, Geither suggested that unflattering details such as this might make him an unviable candidate. The decisions he had been party to at the height of the crisis—allowing Lehman Brothers to fail, bailing out AIG, deploying the hated TARP—might reflect badly on the new administration. He was trying to wriggle out of the job—“I knew it would be terrible”—but Obama wanted him anyway. In retrospect, hiring him seems like a stroke of genius. While the president has taken plenty of heat on economic issues, much more wrath has fallen on Geithner, whose starring role in the bailout drama has seen him repeatedly accused of valuing the interests of financial institutions over the common man, which he patiently explains, for probably the millionth time, is not true. “If you want to protect the economy from a failing financial system, you have to get the system functionally working, and that requires you to do things that look like you are helping the people who helped cause the crisis,” he says. “People describe this as the rescue of the financial system. That’s not really right; it was the rescue of the economy from the failing financial system.” This has been an extremely difficult notion for anyone to accept, not least thanks to the admirable unwillingness of American adults to accept that life sometimes just isn’t fair. “That perception people have, that we gave money to Wall Street at the expense of Main Street, is just a damaging fiction,” he says.

Another fiction that has plagued Geithner is the idea that he is a creature of Wall Street, specifically that he worked for Goldman Sachs. He isn’t sure where it came from—probably just confusion with his predecessor, Hank Paulson, who was the former CEO—but “once it hardened, it was very hard to overcome.” Indeed, he has not really overcome it at all. I can write, right here, in all caps, TIM GEITHNER HAS NEVER WORKED ON WALL STREET, and still someone will comment on our website that he is a bankster who should just go back to Goldman Sachs. Geithner says it’s “extremely unlikely” he will take a job in the world of finance, but the idea that he is somehow, secretly, working hand in hand with that community persists, and every once in a while someone pulls out records of his phone calls and meetings with CEOs as evidence. Geithner is not really sure what to say about that. “I’m the secretary of the Treasury.” He laughs. “How am I supposed to run a financial rescue if I don’t take phone calls from people?”

The issue of phone calls came up again two weeks ago, when the blog Zero Hedge dug up a 2007 transcript of a Federal Reserve conference call in which Jeff Lacker, the president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, said Ken Lewis, then-CEO of Charlotte-based Bank of America, told him that Geithner had blabbed ahead of time the details of a proposed cut to the discount rate. “I would never, ever, ever put myself in a position where I was disclosing material information about a policy thing ahead of time,” Geithner says, though he infers he probably did speak to Lewis and the CEO may have overly extrapolated from the conversation. “When you are the president of the New York Fed, part of your job is to be close to the market,” he says. “It is not possible to do that job locked in a cage of silence and darkness.” But the constant communication “creates that risk, that you are vulnerable to that perception. I don’t know how you avoid that.”

Throughout our conversation, Geithner has retained his Buddha-like calm, although when I ask for the fourth or fifth time if he thought he’d made any mistakes at all, he winces: “I am human, you know,” he says. “There’s this perception that somehow we had other cool things we could have done that would have been better for the average American and we just chose not to do them because we were venal or stupid,” he says. “If it had been possible for us to have protected the economy from a failing financial system, as effective in doing it, getting growth back more quickly and stronger, and done so with a strategy that had much less political cost, we would have done it. It was hugely in our political interest to do it, there was an overwhelming pressure on us to do it, we looked very carefully at how to do it. It’s not that we didn’t think about it, that we didn’t try.

“This is a deeply complicated world, in a fog of gray and ambiguity,” he says. “It’s easier for people to absorb the simple narrative of the black and white. And for them the black and white is, ‘Those are the people that got us in the mess; you saved them and they paid themselves billions in bonuses, and they should have gone to jail, and they are still walking around.’ I don’t know anything powerful enough to overwhelm that simple narrative.” Fortunately, fighting those battles is no longer Tim Geithner’s problem. He hasn’t decided what he’s going to do next, beyond a much-needed vacation with his wife, but says he plans to do some speaking engagements, maybe write a book, and “tread water” for a while. He laughs when asked whether, should the need arise, he’d ever be pressed into service again. “Um, no,” he says, adding quickly, “I don’t regret doing it. I love my work, I love the people I work with, I believe in it deeply. It may look terrible from the outside, but it’s not like that. Even with all of the messy politics, it is really compelling work and it’s rewarding. Even in the midst of all the shit.”

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.