Laying out his deficit-reduction plan last week, President Barack Obama once again tried to be a liberal without sounding like a socialist. For all his oratorical gifts, he’s not done so well at this. Ever since Obama started Joe the Plumber’s fifteen minutes by telling him that “when you spread the wealth around, it’s good for everybody,” Republicans have successfully promoted the perception that Obama’s brand of progressivism has produced an agenda that leaves Americans vulnerable to the tyranny of tax agents, bureaucrats, and foreign lenders.

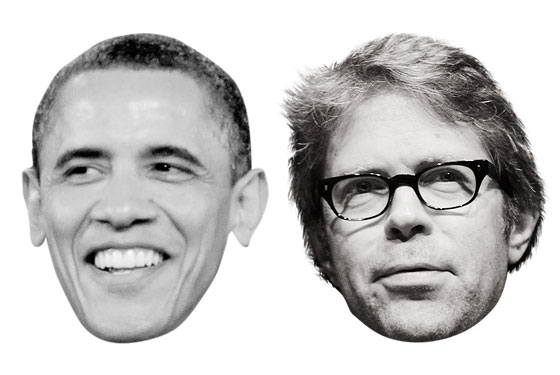

But now Obama has found a response to those attacks. Winding down his remarks at George Washington University, he pulled off a neat rhetorical trick. Obama upended the idea that liberty comes from self-reliance, making the case that liberty is not constrained by community but a by-product of it. “We believe that in order to preserve our own freedoms and pursue our own happiness,” he said, “we can’t just think about ourselves.” It’s an argument that (at least to these ears) has an echo of another liberal hero: Jonathan Franzen.

Talking to the Guardian last fall, Franzen asked, “What is it in the national character that’s making us such a problem state?” His answer: “A childish notion of freedom.” The more adult idea, per Franzen’s Freedom, is that freedom is not what’s gained in the absence of obligations to others but instead found within relationships. The book warns that freedom for freedom’s sake can make for a grim existence. Franzen writes that the matriarch of his story, Patty, “had all day every day to figure out some decent and satisfying way to live, and yet all she ever seemed to get for all her choices and all her freedom was more miserable.” This is the same Patty that Franzen uses as a proxy for conservative ideology, and to whom “the only things that mattered … were her children and her house—not her neighbors, not the poor, not her country, not her parents, not even her own husband.” Only after she shacks up with her husband’s best friend does she realize her mistake and retreat back to her spouse, the only community she ever knew.

We know Obama got an advance copy of Freedom, and in October Franzen paid a visit to the White House—which proves, well, nothing. And yet there are parallels between the way the author’s characters wrestle with domestic-level independence and the president’s attempt to convince voters that committing to the American community is in their own self-interest.

Paul Ryan, a Randian, naturally believes that things work the other way. The Wisconsin congressman posits in his budget proposal that Medicare’s costs necessitate the program’s end, for its recipients’ own good: “The trade-off in terms of lost freedom would be completely unacceptable.” Obama wants to expose that as a false choice. In Obama’s logic, gutting Medicare shifts the burden of health costs not just to seniors but also to their families, who will be forced to sacrifice elsewhere in order to pitch in. Likewise, shortchanging education shortchanges the bootstrapping entrepreneur with jobs to fill. Freedom, in other words, costs money, some of which will have to come from higher taxes. Of course, such nuance is more successful in fiction than in national affairs. But at least our writer-president has found the language to get the idea across.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.