The new Glenn Beck show that launched last week on Beck’s GBTV.com start-up is pretty much the old Glenn Beck show: same 5 p.m. time slot, same crying, same chalkboard, same dire prophecies. As disappointing as this may be to anyone expecting newsmaking antics, among the loyalists paying the full $9.95 monthly subscription to watch his web-TV offering, that familiarity is the point. But there is something noteworthy about the program, in what it portends for a certain kind of media star.

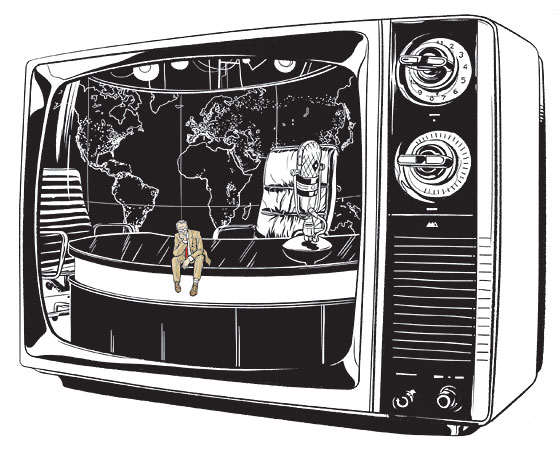

In the simpler days of television past, the star was a strategic asset to be preserved at almost any cost. Until the cable explosion rocked its business model, broadcast TV was like the packaged-goods industry: Minor shifts in market share translated into big profit boosts. Anchors and late-night personalities, much like sitcom headliners, played an outsize role in pulling in the viewers that fattened a bottom line (at least, that’s the message their agents successfully pitched). At ABC News, Roone Arledge famously populated his broadcasts with Barbara Walters, Peter Jennings, Diane Sawyer, and Ted Koppel and triggered an extended arms race among the networks. In 1980, Dan Rather scored an $8 million contract to remain at CBS and take over Walter Cronkite’s newscast rather than bolt for ABC or NBC. He feuded constantly with CBS management over budgets and editorial control but was just too valuable to let go.

In 2005, CBS ignominiously pushed Rather into early retirement—the model had become unsustainable. But the cable networks that fractured the Big Three’s hegemony are no better equipped to put up with talent they can’t afford or control, or both. And today, between the continuing proliferation of channels and broadband and wireless speeds that have made streaming video ubiquitous, TV-news talent have options for self-determination once enjoyed only by their print colleagues, with their escape hatch to blogging fame and fortune. Beck’s decision to take his act to his fledgling subscription site is merely a more radical manifestation of the same trend that’s taken Keith Olbermann from MSNBC to Current TV, Katie Couric from CBS News to her embryonic syndicated talk show, and Conan O’Brien from the Tonight Show to TBS. With their brands firmly established, these personalities can become franchise players for lesser channels or strike out on their own, preserving their big salaries while gaining more control over their content (or, in Oprah’s case, control over an entire channel).

But there’s also a cost to such moves, in the form of decreased influence. GBTV.com may prove a financial success, as might Oprah’s cable network. But as one-person media brands go à la carte, their audiences shrink, at least at first, to their hard-core fans—GBTV has signed up more than 200,000 subscribers, according to The Wall Street Journal, which, though impressive, is a fraction of the 2 million daily viewers he commanded while on Roger Ailes’s payroll. More important, as you move higher up the dial, or off the dial completely, you also have less visibility. It’s been decades since television personalities spoke with anything approaching the voice-of-God authority they once enjoyed. And yet there remains something to be said for being part of an established network, however diminished it may be; Olbermann and Beck, for instance, both attracted more attention partly because of the broader crossfire between MSNBC and Fox News. Perhaps that explains why Beck, ever savvy, has kept his radio show (broadcast on more than 400 stations) and continues to churn out best-selling books with Simon & Schuster. Calling your own shots has its perks, but being part of that larger ecosystem still matters.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.