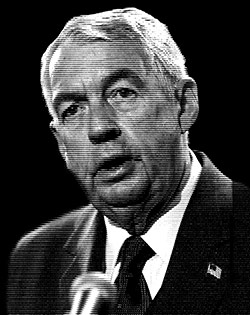

Joe Hynes is coming to prime time. Next week, the Brooklyn district attorney will appear in Brooklyn DA, a six-part series airing on CBS and billed as “a tough, candid look” at the office he’s presided over for nearly a quarter-century. Hynes gave the network unprecedented access to produce the show, an arrangement that appears, on its face, to be a fantastically bad idea, for numerous interlocking reasons.

For starters, Hynes has already been accused of pimping out his public office to CBS, pulling prosecutors away from cases and putting them in front of the cameras, a criticism made more damning by the fact that he’s in the midst of a reelection campaign. The show’s timing, four months before the September 10 primaries, has already prompted one of Hynes’s opponents to sue the network, declaring the series a six-hour free infomercial for the Hynes campaign.

The hype around the series has also become another excuse for critics to dredge up all the other controversies Hynes is embroiled in. Earlier this month, he opened an internal investigation into at least 50 cases handled by a now-retired police detective who, while working with Hynes’s prosecutors, is accused of using false testimony and other duplicitous means to achieve convictions.

The allegations aren’t the only recent claims of misconduct. Hynes’s prosecutors have been accused of failing to share critical evidence with defense attorneys in dozens of cases, and at least three convictions have been overturned in the last few years. Jabbar Collins, who spent sixteen years in prison on a wrongful murder conviction, has sued Hynes’s office in federal court. His lawyers plan to argue that, in the words of one federal judge, Hynes was “deliberately indifferent to the underhanded tactics” of one of his top and most controversial prosecutors, Michael Vecchione. (The gruff Vecchione, long known in Brooklyn for his aggressiveness and penchant for publicity, will also be a featured player in Brooklyn DA.)

Already the series is creating a legal mess. Last week, defense attorney Gerald Shargel tried to prevent footage from airing, after, he says, he learned that a Hynes prosecutor had been filmed prepping a witness for an upcoming trial. “This is a very serious criminal case that should be tried in a courtroom,” he wrote the judge, “not on ‘reality TV.’ ” Susan Zirinsky, the show’s senior executive producer, is adamant that Brooklyn DA will be hard-hitting. “This is not a wet kiss,” she tells me. “You’re going to see the losses. You’re going to see a case get screwed up after two years of hard work.” Still, Hynes agreed to go through with the show—and, somewhat incredibly, without negotiating a chance to review any footage before it airs.

Hynes isn’t too concerned about the fallout. “Look,” he says when we meet, “Did I think for a moment, Gee, this could be a disaster? Yeah. I’ve been around long enough to understand the practical.”

It’s late April, and Hynes is seated at his desk in his airy office, a quiet perch high above the criminal courts and all their attendant chaos. He wears a dark, three-piece banker’s suit, the pinstripes running from his lapels to his Florsheims, a cloud of Brut hovering. On the table in front of him are copies of books he’s written—one true and one fictional—about the crime world in New York with all its saucy dialogue and can’t-believe-it’s-true plot twists. He’s finished writing his third, a novel called The Chairman, about a respected lawyer who’s called in by a mayor to solve a corruption problem, a setup that Hynes himself lived through as a young prosecutor.

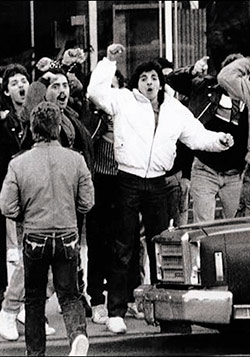

He’s very much his own story. In 1986, when street crime and racial unrest were still the city’s main narrative, Michael Griffith, a 23-year-old from Trinidad, was hit by a car and killed while running from a white mob in Howard Beach. Hynes was tapped to investigate and prosecute the case. His success in gaining convictions against the hooligans made his career. He was approached by reporters daily and learned the importance of television in politics.

“The reality is that I was in everybody’s living room for four months with the Howard Beach trial, so I had a very high profile,” he says. He used his star power to run for office. At first, he was an unlikely D.A., a former Legal Aid attorney and a critic of prosecutorial power. He oversaw the office during the crack-addled early nineties, when there were hardly enough prosecutors to handle the heavy load of murder cases and street gangs. Among colleagues, he became known for his progressive, anti-recidivist programs.

His first serious challenge came in 2005. In a crowded field, Hynes won by a measly 5,000 votes. On the campaign trail, he was shocked by how few people knew who he was.

Hecklers during a march against racism in Howard Beach, 1986. “When I first got the job, I was the guy on the white horse … the Howard Beach guy, Mr. Integrity,” says Hynes.

“Before 2005, I never had to worry about getting reelected,” he says. “I thought for the longest time that Howard Beach gave me an absolute cornered market on African-Americans. That was foolish. If you switched that vote by 2.5 percent, I was gone. It was a mistake I’ll never make again.”

All of which is why green-lighting Brooklyn DA must seem like a good idea to him. It’s a way to get his name back out there: Howard Beach, Part II. He denies the show is an election ploy; the CBS people came to him and made the decision on when it airs. “I didn’t pick the time,” he says, but the show’s schedule has forced him into a defensive crouch.

When the treatment for the series was leaked to the Daily News, the paper jokingly called him a threat to the Kardashians. Hynes bristles at the implication that Brooklyn DA is reality television. “Anyone who knows anything about me would know that I would hardly be involved with a reality show,” he says.

Hynes also isn’t worried about how he will be portrayed. As his own best narrator, he knows the show’s producers can’t make anyone look too bad. If the characters aren’t likable, nobody will watch. “They’re not looking to make a negative show,” he says. He knows some of the stuff they shot, not everything. “They followed one of my executives who loves to cook, an Asian kid, and they followed him around the grocery store,” he says. “It’s a lot of human-interest stuff.”

The human-interest stuff is another reason why the show is such a good move. It changes the conversation and humanizes the office at a time when so many tainted cases are surfacing.

As we talk in his office, an hour goes peacefully by. Hynes’s phone doesn’t ring; aides don’t come barging in. Before he goes downstairs to pick up some cottage cheese for lunch, he dismisses the criticism as overblown, a few problem cases among hundreds of thousands over the decades. He’s not bothered by all the bad press, he insists. He has a secret for handling it. He learned it years ago after his first bad tabloid headline, which he remembers as “1-800-CRONY.”

“Because they’re saying he brings all his cronies in,” Hynes recalls. He was devastated. His instinct was to lie low. He called Louis Lefkowitz, the former state attorney general, who told him to go out to an event—any event. Hynes found a dinner-dance in Bensonhurst and went with his wife. He called Lefkowitz the next morning, and Lefkowitz asked him what happened. “I said, ‘They treated me like traveling royalty.’ He said, ‘Right. Because you’re the D.A.’ ”

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.