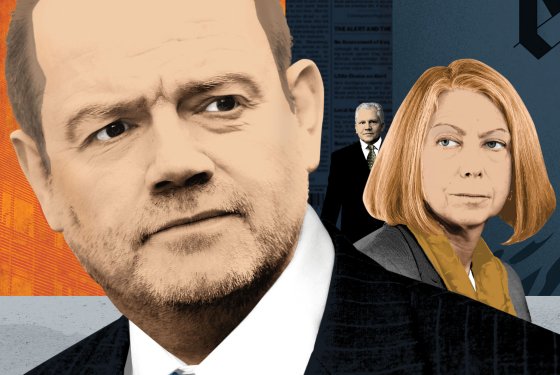

When Mark Thompson, a former director general at the BBC, was appointed president and CEO of the New York Times Company, the reaction inside the company was a mix of relief and apprehension. On the one hand, the chairman and publisher, Arthur Sulzberger Jr., had finally found a business leader for the long-rudderless Times. On the other, his new hire was fighting allegations that he had been negligent in handling a scandal involving a pedophile at the British network. But when Thompson arrived at the Times last fall, uneasiness over Thompson’s problems overseas was soon overwhelmed by anxieties closer to home. Thompson began to appear frequently in the newsroom, and he made it clear he felt very comfortable there.

The Times’ reporters and editors, eager to hold on to the protocols of a legacy media world, hold quasi-religious views about the sanctity of the newsroom against the influence of business concerns. The mere presence of a corporate suit among the journalists was like a belch in a cathedral nave. And yet that view now seems quaint. Sulzberger hired Thompson to transform the Times from a rapidly declining print business into a global, multimedia news brand like the BBC. In August, after the Graham family announced the sale of the Washington Post to Amazon chief Jeff Bezos, Sulzberger and his cousin Michael Golden sent a fevered memo assuring the staff that the Sulzbergers were not about to follow suit. Thompson was the family’s firewall against such a fate.

So when the Times communications staff objected to a trip Thompson and executive editor Jill Abramson were planning to take to Silicon Valley last December, arguing that it wasn’t the Times way for the business and news leaders to appear in public together, Sulzberger overrode the concern.

On that trip, Abramson and Thompson went to dinner parties, one at the house of Facebook COO and Lean In author Sheryl Sandberg. At another meeting, Abramson was obliged to defend him, despite having assigned an aggressive investigative reporter to cover his travails at the BBC. During a moderated event at the Commonwealth Club of California, when Abramson was asked by the host where she envisioned the paper five to ten years from now, she laughed sardonically and peered into the audience. “Mark, would you like to handle this question?” she asked. “No, I’m just kidding.”

But the joke contained an uneasy truth: The role of “visionary” at the paper, traditionally held by the news chief, was now being ceded to Thompson. And in recent months, say several Times sources, Abramson has chafed at some of Thompson’s moves as he redirects company resources to projects of ambiguous design, including an aggressive video unit run by a former AOL/Huffington Post executive who sits among news editors but reports to the corporate side of the Times.

Thompson and I met in his office on the sixteenth floor of the Times building to talk about his plans. He is the first leader to come from outside the Times hierarchy. He spoke about building out a smorgasbord of “news products” to sell to more potential subscribers, including online puzzles and games and a Times-sponsored cruise with editors and reporters to Europe. He discussed a multimedia magazine, a project involving food and dining, and conferences starring Times columnists and hosted by paid advertisers—like the one that featured business writer Andrew Ross Sorkin interviewing the CEO of Goldman Sachs last December and was sponsored by Research in Motion.

What he described is a company where the news itself was a starting point for a brand—not a novel position among media companies now, but one he plans to pursue vigorously in a newspaper culture that’s never much appreciated vigorous change. “The problem many American publications have got is a loss of creative focus,” he told me. “The business-model issues, in the end, are kind of second order.”

When Arthur Sulzberger first met with Mark Thompson in London last spring, he was under duress. Advertising was plummeting, and revenue from the pay wall, the much-heralded plan to charge readers for access to the website, had begun to plateau. Sulzberger had fired the former CEO, Janet Robinson, a longtime Times advertising executive, in December 2011, leaving the company without a business leader for a long period in a dangerous era.

Thompson was hailed by Sulzberger as something the Times didn’t seem to have in house: a digital visionary. Its own version of a web guru, Martin Nisenholtz, had been marginalized by Robinson after a protracted battle over whether the pay wall was a good idea (she was for it; he was against). Robinson was fired, in part because she came up against Michael Golden. As part of her exit, the Times had to shell out roughly $24 million in compensation.

On the surface, Thompson, a rumpled Oxford graduate who was once a news editor at the BBC, appeared to have experience with a comparable entity to the Times, a kind of half-public, half-private media company that was, in spirit, considered less a business than a public good. Thompson, who favors a light beard and checked shirts, made his way up the BBC ladder as an executive who could carefully introduce innovation to a sclerotic institution suffering from legacy issues. At a time of austerity in Britain, Thompson rebranded the BBC as a global multimedia news provider, with an emphasis on TV-quality online video programming. His signature move was the rollout of iPlayer, a technology that let people watch the BBC online, the significance of which Thompson compared to the introduction of color television. He also implemented a five-year plan to slash 2,000 jobs.

Along the way, he was an astute corporate gamesman. As a British media source told the Observer in a 2001 profile, “He’s very good at figuring out exactly what buttons to push with people. For one person it may be money; for another it’s a program idea or promotion. He’s a very good amateur psychologist. It’s a huge strength but sometimes—when you realize he has played you—you feel you’ve been had. Markism, we call it.” As a British observer says, “The one thing he did [at the BBC] is he survived. It’s an incredibly hard place to survive in.”

Thompson’s handpicked successor to lead the BBC, George Entwistle, resigned within weeks of starting, followed by a series of scandals that rocked the BBC, which eventually led to parliamentary hearings into excessive severance payments to top BBC executives under Thompson and a roughly $150 million digital venture that Thompson said was crucial to the future of the BBC but that appeared to vaporize without consequence. Thompson, it appeared, had got out just in time.

When he arrived in November, all people at the Times knew about him was his ambiguous role in an electric British news scandal over the network’s handling of the revelations that their star, Jimmy Savile, a comedian who died in 2011, was a raging pedophile. Journalists at the network planned a documentary about Savile’s behavior; it was squashed by higher-ups and a celebratory retrospective was aired. Thompson said he had no idea his own news organization was preparing a documentary on Savile until someone mentioned something oblique about it at a cocktail party. Some senior Times executives urged Sulzberger to reconsider or delay the hire, and the board of directors held a meeting to discuss what to do. Sulzberger, however, could ill afford to reverse course. In just a decade, the Times had shrunk from being an over $6 billion company of newspaper groups and TV stations and Internet properties to just the Times itself, which was now valued by the market at a little more than $1 billion. So last October, Sulzberger announced he was “satisfied” that Thompson hadn’t known about the report on Savile, adding that the Times would protect its integrity on the matter by vigorously covering the unfolding BBC scandal. The Times agreed to pay Thompson an annual salary of $1 million, as well as a signing bonus up to $4.5 million if the company met certain performance goals.

Thompson is from a press culture where the line between news and business has never been particularly sacred, and he saw himself as a new kind of fusion executive. He told a Times executive that there was no job at the paper he couldn’t perform, including Abramson’s. “I could be the editor of the New York Times,” he said. “I have that background.”

In a memo last March, Thompson and Sulzberger stated expressly that the newsroom would be working more closely with the business side. “We are, of course, preserving the historic editorial independence of the newsroom from commercial influence,” they wrote, “but also promoting a closer partnership between the newsroom and the rest of the company as we develop our products and services.”

As part of the reorganization, the Times has created a new category of product managers in which top newsmen like Gerry Marzorati, once the editor of the Times Magazine, would report to business executives, creating conferences and other extensions of the brand.*

In our interview, Thompson showed me a chart he drew with black marker on white drawing paper that showed the “engagement curve” of the Times’ estimated 50 million readers, who range from paid subscribers on the high end to people who click on a single link on the long tail. He described a scenario in which the paper offers an array of products and subscription offerings to readers both up and down the chart, but especially the middle, where readers might respond to lower-priced Times products. Of all the paper’s efforts to reshape its business, says Thompson, “by far the most important, in my mind, at the moment, is what I hope is going to be the growing suite of paid products.”

For instance, he says, the Times recently launched a mobile subscription that lasts for four weeks, aimed at those who don’t want the entire print paper or full online access. And soon there will be more: the recently announced “Need to Know” project, a small “curated subset” of the paper that will sell for a reduced price; and a stand-alone online magazine that the Times will sell individually for tablets and the like. “We’re going to thicken the pot with things like video, with new form factors, new devices,” he sums up, “but the point of the exercise is not about the means but the sense of the relationship—if you like, the indispensability of the Times, hopefully, for a lot of people.”

Thompson is short on specifics. But he takes great pains to emphasize that Abramson is the source of creative efforts to reinvent the Times as a digital enterprise. “Although the business side can identify gaps in the market,” he says, “the newsroom should be the natural leader of the creative thinking about where new expressions of our journalism should reside.”

But Abramson is doing more to adapt to Thompson’s designs than vice versa, and with diminishing resources. Last spring, she made a wave of new editorial appointments, including the elevation of Danielle Mattoon to culture editor (she was recently fêted at an event co-hosted by Thompson). She also assigned new and younger candidates to major jobs, like “Book Review” editor Pamela Paul. Abramson was putting more women in power, as her own appointment had portended, but ironically the Times could not pay them the same salaries as the men who’d previously had the jobs—not because Abramson respected them less, but because the money is needed for other ventures.

Tales of austerity are rampant at the Times nowadays. The deputy editor of the op-ed page, Sewell Chan, recently posted on Facebook that he needed a place to stay while on business in Europe. A Portuguese online edition of the Times, which Sulzberger publicized with great fanfare on a trip to Brazil last fall, was considered too expensive and never launched.

Meanwhile, the recent sale of the Boston Globe and Worcester Telegram & Gazette for $70 million, an almost 95 percent loss in value from the approximately $1.4 billion the Times paid for the properties, means the paper must eventually report a significant loss in upcoming quarters.

Abramson is executive editor at an excruciating time for the paper, but she has maintained the Times’ high journalistic standards. Last year, the paper earned more Pulitzer Prizes than it had since 2009; its leadership in coverage of major events like the turmoil in Egypt is unmatched. The investigative journalism during her tenure has been aggressive, taking on the Chinese leadership’s money entanglements, or Apple’s and other companies’ foreign labor practices. But her job is also to manage an anxious newsroom, and that is more difficult. In February, when the staff held farewell parties for two popular veteran (and, by Times standards, expensive) editors, Jon Landman and Jim Roberts, who had been encouraged to take buyouts, Abramson left on a trip to Cuba with her sister. “I remember at one point Jill announcing she was leaving on this vacation because she was exhausted by all the tension of the buyout,” says a colleague. “Oh, I’m sorry, it was even harder for the people who were leaving.”

By late April, these critiques erupted in a story by Dylan Byers of Politico, which described a meeting between Abramson and managing editor Dean Baquet in which Abramson’s manner so infuriated the ordinarily affable No. 2 that he stormed out of her office, slammed a wall, and left Times headquarters. The story featured several anonymous quotations attacking Abramson in personal terms.

Critics shredded the story as a sexist attack by faceless cowards who might have otherwise celebrated her toughness had she been a man. Still, the account was an expression of dissatisfaction with Abramson among important editorial constituencies like the Washington bureau, and the details of the incident highlight aspects of Abramson’s sometimes abrasive style, which she herself has dubbed “Bad Jill.” According to two sources, what precipitated the wall-punching incident was this: She had just returned from another trip and was critiquing the front-page stories that Baquet had published in her absence, calling each of them, one by one, “boring.” Baquet, who had managed the emotional farewells of departing editors while Abramson vacationed, protested by offering a story that he felt was important. After a long pause, Abramson simply declared, “Booooo-riiiing.”

In a previous time, acting like an autocrat was standard practice for executive editors. Her predecessors with brusque styles included Abe Rosenthal, a powerful editor who radically reinvented the paper in the seventies, and Howell Raines, the ousted (and also transformative) editor with whom Abramson once openly warred—and to whom she is sometimes compared.

Her defenders say she has become more sensitive to the jitters of the newsroom. “Is Jill the best listener?” asks David Carr, the paper’s media critic. “No. I think she heard the criticism coming into her job, though, and has made significant efforts to be open-minded. Maybe she hasn’t listened to everyone, and maybe that’s why she ends up with a piece like [the one in Politico].”

For his part, Thompson says the paper is not so much cutting back as creating a new “skills mix.” “We’ve been going through a process at the New York Times of a change in the talent and skills mix you need in a modern newsroom,” he says. “Many people have gone and many people have arrived, designers and videographers coming in the newsroom. It’s not been a sense of cutting back; it’s changing the mix.

“It’s incredibly important that we get the amount of money we spend on everything right,” he says, “particularly in the newsroom.”

In place of the 30 reporters and editors who left last winter, the Times is hiring dozens of videographers to create new content for the paper’s website. And in February, it was Thompson who hired a general manager of video production, Rebecca Howard of AOL and the Huffington Post, to oversee the new video push. Though she was billed as part of a “video-journalism” effort, Howard is a business executive with an office in the editorial suites. When it was announced that the video unit would be reporting to the corporate side of the paper, “Jill was clearly shaken by it,” says a person who was in meetings with her.

Thompson argues that Abramson is very much involved in the paper’s video efforts. “It’s not been imposed on the newsroom,” he says. “It’s a big part of Jill’s agenda.”

The video rollout is an important part of Thompson’s ambitions to create a genuinely multimedia Times. Pushed on specifics, however, Thompson has little to reveal about what Times video will look like. “What I’ll say about video: It’s not there to replace great written journalism,” he says.

Of course, there’s ample skepticism about the value of the video unit. Some observers wonder if Thompson is only pursuing it because it’s what he knows from his tenure at the BBC. And besides, it’s hugely expensive to do well, especially against competitors like Google and Facebook.

The most-watched videos so far have mostly been on the softer side of the news. Thompson has enthusiastically pointed out to colleagues that one of last year’s most popular videos was an instructional on how to roast a turkey for Thanksgiving. “I’m not ashamed of the fact,” he adds, “that in the sections of the newspaper, in areas like dining and travel, that we’ve got big characters and we can make attractive video there as well.”

Thompson meets regularly with reporters and editors, but he is still a mystery. “There wasn’t a grand plan,” says one reporter who heard him out. “Maybe there isn’t a grand plan. Sell tchotchkes, do this, do that. You could reasonably infer what he’s talking about is chipping away at that wall between business and news.”

As the chief defender of the newsroom, Abramson has evidently made that inference, occasionally chafing at Thompson’s authority. She “thinks he is moving far too quickly and far too haphazardly in knocking down the wall between journalism and business,” says a person with close ties to the editorial ranks of the paper.

“There’s a general sense that [Thompson] is off trying to create new products and new ideas and go down a hundred roads,” adds a prominent columnist at the paper. “And I’m not sure he’s keeping her in the loop on all those roads.”

Thompson and Abramson are partners, but the partnership is not easy. In a memo last month, Abramson announced with fanfare that Sam Sifton, the editor of the national-news pages, would be stepping down from his editorial job to help invent a new online magazine, as well as an unnamed project with a focus on food. She managed to move Sifton, a favorite of hers, off the national desk, where he was considered a talented writer and editor but a poor fit for the job, and put him on a new digital project that was not her idea. The online magazine, which promised more content like last year’s Pulitzer Prize–winning multimedia interactive story “Snow Fall,” was the brainchild of the corporate side of the Times.

Asked about the genesis of the new web magazine, Thompson says, “Well, [Abramson’s] certainly expressed her enthusiasm to me about that idea. I can’t remember who came up with it.” (In fact, the idea was inspired by the corporate consulting firm McKinsey & Co., whose research showed that food and politics were areas of opportunity for developing editorial products.)

Abramson has told a friend outside the paper that she feels isolated and without allies. When I called Abramson to ask for an interview, she laughed and replied, “Do you want to cause me to kill myself?”

Given the obvious tension with Baquet, Abramson has lacked an ally who can act as a partner as she tangos with Thompson. Last spring, she began a round of discussions with James Bennet, the editor-in-chief of The Atlantic. She floated the idea of a masthead position at the paper with a focus on the web, but Bennet turned it down.

Abramson recently appointed Sulzberger’s son, Arthur Gregg Sulzberger, formerly a reporter in Kansas City and then “Metro” desk editor, to a special position overseeing “a new ideas task force … that will think up and propose new ways to expand our news offerings digitally.” (Around the same time, another Sulzberger relative, David Perpich, was given a similar role on the business side; between Perpich and Arthur Gregg, the moves set up a line of succession for the next generation after Sulzberger, who will be 62 in September, and Michael Golden, age 64, decide to retire.)

Perhaps nothing has highlighted the shifting fault line between Abramson and Thompson more than the loss of Nate Silver, the data cruncher and presidential-campaign prognosticator, to ESPN and ABC News last month. During the election last year, Abramson made clear how much she valued the attention Silver brought to the Times’ political coverage. Of the Silver-inspired surge in Times online readership, she said: “They weren’t coming for the rest of the Times; they came for him.” So as Silver’s three-year contract neared its end this August, the Times began a series of discussions to keep him. In his first contract with the Times, Silver had turned down more money elsewhere in order to stay. This time, Silver wanted an enlarged role at the paper, including a bigger staff and a wider editorial scope beyond politics. He expected his employer to develop his trademarked FiveThirtyEight website and brand on other platforms, like TV, and in other news sections, like sports. Abramson put on a full-court press, and for a while she believed he might stay, telling Silver the Times was the “prettiest girl at the dance.”

So when Silver announced he was leaving, Abramson was angry. Some of her staff blamed her for the loss. “If Jill had been more aggressive early in the year, it never would have come to this,” says a reporter.

But the major reason Silver left was because he felt it was Thompson who had not committed to building his franchise. The mixed signals from Thompson and Abramson—his lack of enthusiasm for committing resources to Silver, her desire to keep a major star—frustrated Silver and his lawyer. The two Times executives did not appear to them to be on the same page: During one meeting, Silver and his lawyer saw Abramson roll her eyes at the Times CEO.

For Abramson, Silver was a tentpole attraction for her favorite subject, national politics, and brought the kind of buzz she thought valuable. In an interview, Thompson confirmed that keeping Silver was not at the top of his agenda: “I would not say it was an overwhelming priority,” he says. “During the election period, he was obviously a very significant figure. Off-season, it’s a slightly different story.”

Thompson says his strategy “does not depend on keeping any one journalist or any one business leader or anybody.” But, then, who does it depend on? The business of the Times is now being run by three executive managers, Sulzberger, Golden, and Thompson, who between them soak up almost $13 million in compensation. In a meeting this year, Golden told colleagues he liked Thompson because Thompson listened to what he had to say—a crystal-clear dig at former CEO Janet Robinson.

Asked if that kind of top-heavy management is necessary to run a newspaper, Thompson replies that the changes he is bringing to bear are “colossal”; therefore, “I think the idea of having a large and strong management team makes sense.”

Meanwhile, Thompson continues under the glare of an ongoing investigation. In September, he will reportedly testify about what he knew of excessive severance compensation paid to some top executives under his leadership. The Times’ coverage of these matters has been minimal.

Thompson says he’s not distracted by the drip feed of bad news about his role at the BBC. “No, I’m completely engaged,” he says. “I mean, I’m fully engaged in the job I’ve been asked to do here, and I’m really enjoying it.”

But he also confesses that his plans—the answer to that question posed last December in San Francisco about the future of the paper—have barely gotten under way. “It’s far too early to reach any conclusions, good or bad, as to how that’s going,” he says, adding, “You should ask others.”

Thompson says his presence will just take some getting used to. “Is the New York Times getting to know me? And am I, compared to the past, more visible than past CEOs? Yes. Whether that leads to success, we’ll see.”

*This article has been corrected to show that in his new role as assistant managing editor for new initiatives, Larry Ingrassia, formerly of the business page, reports to Jill Abramson.