History will record that in the waning days of Michael Bloomberg’s empire, rebels massed and developers erected fortifications. At last Monday’s meeting of the City Planning Commission, the projects advanced one after another, like trains to the front: a thousand-foot luxury tower near the South Street Seaport; a dozen buildings on the Greenpoint waterfront; the residential redevelopment of Bushwick’s old Rheingold brewery. When Commissioner Anna Levin lamented the fuzzy details of a rezoning proposal designed to add new skyscrapers to midtown’s East Side, Chairwoman Amanda Burden said it was “as much as we could shape now.” With time running short, the supersizing plan was moved to a vote, scheduled for this week.

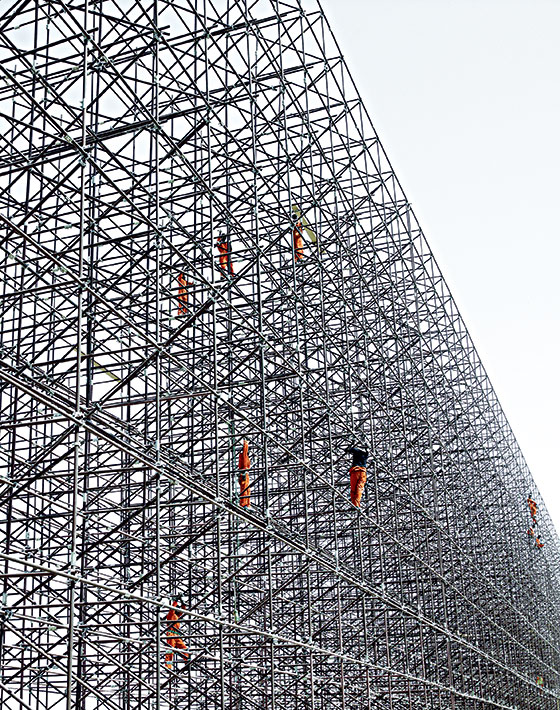

Every mayoral administration ends with a rush to complete unfinished business, but this autumn, within the city’s real-estate industry, there’s a distinct fall-of-Saigon feeling. Bloomberg’s administration has shown unbridled enthusiasm for building, and real-estate people despise political unknowns. So developers are hastening to finalize plans in a last-minute barrage amounting to many millions of square feet of new construction. None of it will be built before Bloomberg leaves office. But there’s value in city approvals: They will remain as facts on the ground for the next mayor.

The rush has been picking up momentum all year, but it’s taken on an intense urgency with the populist surge of Bill de Blasio, who campaigned on higher taxes for the rich, while bashing Bloomberg and “towering, glitzy buildings marketed to the global elite.” His unexpected Democratic-primary victory has inspired what one supporter called “collective freaking out in the real-estate community.”

In his Primary Night speech, De Blasio pledged to tame a marketplace “where luxury condos had replaced community hospitals,” a thinly veiled reference to the Rudin family’s redevelopment of St. Vincent’s, and in a recent interview with The Real Deal, he called for a “reset” in the city’s relationship with developers. “Everyone’s scrambling,” said one developer who has been involved in multiple large-scale projects. “This is a real serious enterprise, and you can’t be a pie-in-the-sky theoretical person, saying a tale of two cities, like Charles Dickens.” (He asked not to be named, conceding that he would probably end up donating to the front-runner’s campaign anyhow.)

“There’s fear that this is a return to Abe Beame’s New York,” said a real-estate attorney who represents major property owners in Brooklyn, summoning the ghost of the seventies mayor. The anxiety has even filtered down to some buyers. One high-end real-estate broker described showing a multimillion-dollar High Line listing to a couple who felt the pressure to act. “They said that this city wasn’t going to be for the ultrarich anymore after Bloomberg leaves,” she recalled. “It was like, ‘We’re never going to find something so great; things like this are not going to be built.’ ”

That’s one fear, at least, that’s unlikely to be realized anytime soon. For months, developers have been funneling new construction into the pipeline. Gary Barnett, the developer of the billionaire lair One57, is arranging Chinese financing for an even taller building down the street. This week, the Landmarks Commission will review a proposal for a skinny spire designed by SHoP Architects for similarly elite buyers. Slightly down-market, there are the waterfront megaprojects, like developer Two Trees’ proposal for Williamsburg’s Domino Sugar site (also by SHoP) and Greenpoint Landing, both of which are pushing for Planning approval.

Swamped city officials have been struggling to balance private-sector demands with the mayor’s priorities, the biggest and most controversial being the East Side rezoning. At the Planning Commission hearing, an official presented renderings of new pedestrian plazas and other benefits to be funded by development fees. But De Blasio, like other critics, has expressed some skepticism, calling for further concessions from the private sector to fund mass-transit improvements.

That may be a sign of things to come—or he may just be campaigning. “Bill is such a smart political tactician, and it’s not clear how committed he is to the anti-real-estate rhetoric,” says a real-estate executive who has known him for years.

Notwithstanding the expectations of some of De Blasio’s giddier supporters, who talk as if he has a plan to redistribute Brooklyn brownstones, developers who know him say he is a man you deal with. “He struck me, from the beginning, as very practical,” said David Von Spreckelsen of Toll Brothers, who won De Blasio’s backing for a controversial project his firm proposed along the Gowanus Canal. “You can’t take any of the rhetoric about going back to the Dark Ages seriously,” said David Kramer, of the Hudson Companies, who’s raised money for his campaign. “Anyone who knows Bill understands his commitment to economic development.”

The pessimistic developers talk about De Blasio like he’s a leftist comandante, while the optimists assume he’s just saying whatever it takes to get elected—but none of them are willing to sacrifice profits to build cheaper apartments. Like Bloomberg, De Blasio says the city has an urgent need for affordable housing; where he differs is in the forcefulness of his methods. Bloomberg has used optional zoning bonuses and tax breaks to encourage developers to allot space to affordable housing, but De Blasio’s platform calls for making those same set-asides mandatory. Builders and construction unions are certain to resist. “If you put down a mandate and the market is very weak, you can shut down an industry quickly,” says Kathryn Wylde, president of the Partnership for New York City. “He’s got the background to know that.”

“Whether De Blasio realizes it now or he figures it out later, if he really believes in affordable housing, it’s not going to create itself,” says one executive involved in several such projects. Precedent would suggest that every mayor eventually comes to terms with developers—it’s the only way anything ever gets built. Bloomberg came to office believing that optional incentives could nudge the private sector to build or preserve affordable housing, but after seeing disappointing results—fewer than 3,000 units since 2005, according to one study—he fell back on offering something developers really value: free land.

The other day, the mayor unveiled a mixed-income development called Essex Crossing, to be built on the site of a city-owned market and parking lots on the Lower East Side. While he brusquely dismissed reporters’ questions about his legacy, the announcement could be read to say: Here is your real tale of two cities. Half of Essex Crossing’s 1,000 units will be market rate and half subsidized.

To some of De Blasio’s supporters, that result might sound like a sellout to developers. But it’s easy to imagine that a few years from now, a Mayor De Blasio might take credit for overseeing the creation of thousands of affordable units at Essex Crossing and other projects now in development. Every mayor capitalizes, to some degree, on groundwork laid by his predecessor: Think of poor David Dinkins, who set Times Square’s revival in motion, only to watch Rudy Giuliani bask in all the accolades. How will this revolution end? With a ribbon-cutting, most likely.

Have good intel? Send tips to intel@nymag.com.