Up above, in the boundless reach of infinite space, two great galaxies, Andromeda and our own Milky Way—millions (billions!) of planets and stars, drawn together by implacable gravity, entwined like lovers in eschatological foreplay to a new and bigger bang. This was how cataclysm came to the physical world, droned the unseen voice of Robert Redford—an endless cycle of attraction and shattering collision, creation, and destruction, leading to more and different creation.

“Sexy,” remarks the Gooch, his shaggy head reclined onto the seat-back at the Hayden Planetarium.

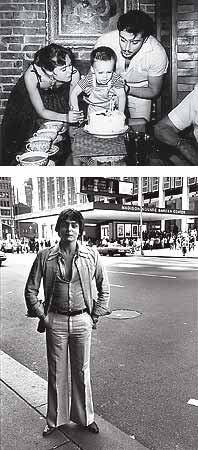

Years ago, before his family moved from Italianate Brooklyn to swinging London, where his father, the famous Gooch the Elder, would start the Ur-seventies stroke book, Penthouse, Bob Guccione Jr. used to go to the Museum of Natural History with his cousin Lenny. The 6-year-old Bobby Jr. stared at the dinosaur bones and wondered, How do you catch those things? The question vexed him for years.

Now the Gooch knows better. He ought to. After founding Spin magazine in 1985 as the tuff-punk antidote to the calcifying rock orthodoxies of Jann Wenner’s Rolling Stone (just as the lounge-lizardly Penthouse thrust itself full frontal upon Hef’s pipe-smoking Playboy) and an uncertain sojourn in the laddie market with Gear, Guccione Jr. is currently the CEO of Discover, the science magazine he purchased from the Walt Disney Company last fall for $20 million.

“As the publisher of a science magazine, I know people and dinosaurs did not live at the same time,” the Gooch says, his Cockney accent still extant despite his having spent the past 35 years in the U.S. “It’s part of the family business.”

By this, of course, Bob Jr. is referring to Bob Sr., whose pungent legacy the younger Gooch has carried about, Aeneas-like, with ever-compounding complexity, at least since those early London days. “That was when I first became aware of who my father was, at least in the minds of others,” says the Gooch, who recalls being a young boy walking past newspaper kiosks hawking stories about an “American sex-maniac pornographer” being denounced in Parliament. “It wasn’t until later that I understood that pornographer was my dad … Such are the hands one gets dealt in life.”

That said, science magazines course through the familial helices of the House of Gooch. In 1978, with Penthouse at its split-beaver Zeitgeistal zenith, Bob Sr., in between emptying his Savile Row–tailored pockets to produce Gore Vidal’s colossally bizarre Caligula (Sir John Gielgud claimed to be shocked—shocked!—that hard-core material appeared in the film), founded Omni magazine. Wired-before-Wired, the bountifully neo-psychedelic Omni, a mélange of dystopic sci-fi, woolly paranormal speculation, and “hard” science articles, was a smash. By the early eighties, it was selling more than a million copies a month. Gooch the Elder, never shy with a grandiose vision, declared the magazine “a launchpad to the future” and nearly bankrupted himself by single-handedly funding a cold-fusion project that would employ 82 scientists and cost $17 million before being shut down.

Discover, Bob Jr. knows, is a way-more-sober thing. With a hefty 700,000 paid readership base, positioned smack between the nut-and-bolt suburbiana of Popular Science and the dishdishery of Scientific American, Discover has long been the field’s general-interest mag: full of topical, well-written and -reported (lots of quotes from scientists and academics) but not overly technical articles. It is the science magazine for the interested layman. In 2004, cover stories included the potentiality of space probes to the planet Mercury, a report on the life cycles of single-cell microbes on the ocean floor, a debunking of “brain chips” for mind control (gray matter, it seems, rejects the Manchurian Candidate scenario), and a tribute to Einstein featuring essays by the likes of Walter Isaacson.

In part, it was this surface respectability, more suitable to the middle-aged gentleman publisher, that attracted Gooch (an even 50 now) to Discover. Such was not the case during the enfant years at Spin, where the daily routine included in-office drive-bys from the rap group N.W.A., Ice Cube and Eazy-E included. Straight outta the Regency Hotel, the boyz took issue with how they’d been depicted in the magazine, a position Gooch was hard-pressed to dispute since he knew the writer of the piece to be “ferrety.”

Famous is the dustup between Gooch and Axl Rose of Guns N’ Roses. The paranoiac Rose, shaking his diminutive fist in protest at the way rock-press barons were “rippin’ off the fuckin’ kids payin’ their hard-earned money to read about the bands,” called out Guccione in the tune “Get in the Ring.” It goes, “Bob Guccione Jr. at Spin / What? You pissed off cuz your dad gets more pussy than you? / Fuck you / Suck my fuckin’ dick … / Get in the ring motherfucker / And I’ll kick your bitchy little ass / Punk.” With ten years of full-contact karate under his belt (his first publication was a homemade ’zine titled A Step-by-Step Guide to Kung Fu), Gooch challenged Rose mano a mano. Rose demurred, proving the rocker to be, Gooch says, “a cowardly dirt man.”

There were other, less colorful episodes at Spin, including a nasty sexual-harassment suit filed by a writer who claimed that Guccione Jr. had “sexualized the workplace.” Although a jury awarded the woman $100,000, Guccione Jr. avoided personal blame. But even if Spin had its bumpy moments (a longtime writer says, “Bobby’s the greatest guy in the world until you work for him”), much good stuff got through. The punchy music coverage—reports of the whereabouts of netherland rock legends like Ike Turner were classic—often buried Rolling Stone’s slumbering corporatism. Norman Mailer and William Burroughs wrote long pieces. William Vollmann was a regular, traveling the whorehouses of the planet on Gooch’s legendarily difficult-to-extricate dime. In the end, however, perhaps Guccione’s most impressive act at Spin was leaving it. He started the magazine with $2.5 million borrowed from his dad—leading to a dispute over ownership that would result in an epic eighteen-year falling-out between the two—and sold it in 1997 for a reported $43 million. When Spin changed hands again this year, it fetched a piddly $5 million, a figure Gooch calls “staggeringly pathetic.”

As befitting a prince of the House of Gooch, there were a number of memorable liaisons along the way. Staying at Gore Vidal’s house in Ravello, Italy, during the shooting of Caligula, Bob Jr. found himself fixed up with the daughter of Imelda Marcos, who arrived with several ninja-style bodyguards. “She was a stunningly beautiful girl, but we did not have much to talk about.” This is typical of his “somewhat miserable record in blind dates,” Gooch reports. Once, Bo Dietl, the grandstanding ex-cop, invited him to Rao’s. “ ‘Don’t bring a date,’ he said. ‘I’ve got someone for you,’ ” Bob Jr. recounts. “He did, too. Brooke Shields. And her mother.” Other boldface hookups included Candace Bushnell and a dalliance with conservative brimstoner Ann Coulter.

“Ann wasn’t always the strident, hate-filled creature she is today,” Gooch laments, ruefully adding that his tombstone will likely read HAD A WEAKNESS FOR TALL BLONDES. He knew the relationship was doomed when the Monica Lewinsky scandal broke. “It’s the middle of the night, we’re in bed, and the phone rings. Ann is jumping up and down, yelling gleefully, ‘We did it, we did it!’ The next morning she’s got three separate televisions going so she can watch all the coverage at once. It was appalling. Poor Ann. It is always sad when the persona eats the person.” For her part, Coulter denies ever being “arm candy for Bob Guccione Jr. The Gooch was my arm candy—my boy toy whom I regretfully had to replace with a much younger man.”

“I have no problem whatsoever accommodating, side by side, the ideas of multiple universes and the Immaculate Conception,” says Gooch.

Watching Gooch glad-hand David Pecker at Bonnie Fuller’s recent book party at the Core Club (seeing Fuller, “a good friend,” with Helen Gurley Brown, Gooch declared, “There’s the money shot!”), a cynic might conclude the younger Guccione is exactly the man casual haters have often assumed him to be: some carousing Pinch knockoff of the ol’ Punch block, one more Murdochian son, of a decidedly lower order. This would be an error, since despite the fringe benefits of his parentage (“People come over to me to say, ‘Gee, thanks. Without Penthouse, I don’t know how I would have gotten through high school’”), the Gooch is a peculiar sort of fortunate son. No Skull and Bones collector of gentleman’s C’s, he dropped out of high school in Tenafly, New Jersey, where his mother settled following her divorce from Bob Sr. “I spent a lot of my time taking care of the rest of my family, because I was the oldest,” he says. Any way you cut it, none of this sounds like a résumé usually found in the often-staid precincts of science publishing.

“I don’t think anyone knew what to expect from him,” says one Discover contributor. “Son-of-Penthouse, Spin, it is pretty incongruous. People wondered if they were going to have to write about the chemical composition of Madonna’s douche and do choral renditions of ‘She Blinded Me With Science.’ ” Gooch did not assuage this unease when he was quoted in the Times saying, “To me, scientists are people who by definition live outside the norm, floating in zones that have never been reached before … people with strong egos and God complexes. That sounds like rock and roll to me.”

Several months in, the vibe remains mixed. “The science audience doesn’t follow the normal magazine rules,” says one longtime science writer. “He talks about ‘rock stars,’ but past celebrity types like Brian Greene and his string theory, the hard-core science reader is more interested in the microbes than the microbe hunter. Discover is not a scholarly journal, but you better know what’s in those journals. The fact is, most people in the field read the magazine. Most of the letters to the editor come from scientists. You’ve got to have your shit straight or they will notice.”

Says another writer, “When he first came in, there was a big meeting where he introduced himself and said not to worry about changes at the magazine. That lasted about a week before the layoffs and the cuts started.” Within weeks, both Steve Petranek, the respected editor-in-chief, and Dave Grogan, the articles editor, decided to leave. (Petranek remains as a consultant.) The writer says, “Losing people like Petranek and Grogan, who know the turf, can be a disaster. You just can’t plug in another person like you might somewhere else.”

Perhaps more pressing is the deep shortfall of ad pages, a persistent problem during the Disney régime. Ads were off 16.5 percent in 2005 alone, and the magazine has taken to running cut-rate full pages of funky-looking spots peddling “historic” gold coins and home water-recycling devices. The see-through paper stock only calls attention to the Karen Carpenter feel of the book.

Gooch, ever upbeat, calls these “momentary problems.” Science readers “have to wash their hair and drink Chivas like everyone else.” And despite ripping up a recent issue at the last minute to insert a “timely” piece on terrorism, he discounts the notion that he really wants to put out an Omni redux, complete with interviews of kindly abductees like Betty and Barney Hill. “I’m not a moron, you know,” he says. “I am not about to crap on my own brand.” Even if he keeps regular appointments with a physics-professor friend who “explains the universe to me on my eighth-grade level,” Gooch contends, “my supposed lack of knowledge is irrelevant. In a way, it’s good, because, like the reader, I’m here to learn, be taught and astounded.

“Once I thought rock and roll would change the world. I loved that idea. I fought for that idea. But science really does change the world. Every day. The idea is to let as many people in on that fantastic adventure as possible—to make them feel the romance of the plunge of human intelligence into the unknown. That’s the mission here at Discover.”

That’s the Gooch. So what if he doesn’t understand relativity? He ran Spin for a dozen years and never, ever, listened to a Robert Johnson record. It is part of the Guccione family tao: the sense of mission, the messianic zeal for space exploration, better blow jobs, etc. Always captain of the ship (he’s never worked anywhere he wasn’t the boss), Gooch charges ahead armed with a somehow charming cut-throat trust in himself and his product, whatever it may be. It is easy to be swept away by the sheer enthusiasm of it all. As he once sat on his leather chair/throne at Spin’s mucky 18th Street office, extolling the planetary indispensability of Juliana Hatfield, some chick rocker on that issue’s cover mostly on account of being kinda hot, he now shakes his pom-pom for the unearthing of dinosaur soft tissue.

“It must be something in the Sicilian makeup, a kind of crusading quest exceeding even an undying need to be cool” that makes Gucciones long to possess science magazines, Gooch says. “There is an aspect of true belief in it.” Indeed, it is Gooch’s “capacity for faith” that has caused a stir amid the resolutely rationalist precincts of Discover. “It shocked the staff, that I’m a believer, that I go to church.” At one of his first editorial meetings, Gooch recalls “an audible gasp in the room” when he proposed a story on how the Vatican verifies the validity of the claims of stigmatics—those who display the wounds of Christ. “What are the criteria of their inquiry, the burden of proof?” Gooch wanted to know. “The idea was to investigate the scientific method of something thought of as totally unscientific. I want the magazine infused with a more philosophical vision of what is and what is not.”

For Gooch, an erstwhile altar boy who describes himself as “a lazy but devout Catholic,” science is incomplete without the contemplation of faith. “I have no trouble whatsoever accommodating, side by side, the ideas of multiple universes and the Immaculate Conception,” he declares. “There is a line where what can be proved and what cannot meet. The line is forever moving because science is pushing against it, forging out to the edge of what can be known. But the line is always there, and like Johnny Cash, this is the line we walk.

“What is science, after all, but one more belief system, another religion?” Gooch is fond of saying. Never to be confused with an easy mark, he contends the very act of believing makes him happy. And walking out of the planetarium after hearing Robert Redford explain how even if the moon might be billions of years old, it was likely formed in a matter of weeks (owing to colliding cosmic debris), Gooch is ebullient.

“Try taking that on faith,” he says, exalting in his own acceptance of the impossible-to-absolutely-prove primacy of the Big Bang’s lifting him up in the same fashion as the influx of the Holy Spirit buoys a Pentecostal tongue talker.

In these times of so-called intelligent design and the politicization of that tenth-grade biology class you kept flunking, such relativist commentary on the part of the publisher of a widely read science magazine can be taken as the act of a double agent in the culture wars. In fact, a number of Discover staffers reportedly indicate they may hurl the next time Guccione uses the term wonderment. The issue came up during the planning of the May cover story on the astronomer Michael Brown and his search for new planets. Instead of standard techie starry-night imagery, Gooch went lo-fi.

“I got a piece of black construction paper, stuck holes in it with a pin, and put a light behind it to stimulate stars. For the planets we used marbles. The art department didn’t get what I wanted until I told them to make believe they were doing a second-grade science-fair project. When it was over, everyone agreed it worked. By using a kid’s image, instead of something like the Hubble, we captured the profound innocence of looking into the sky. That whole cover cost me, like, $20.”

The notion that Gooch considers owning Discover an enabler of his inner child (re)opens a whole new line of inquiry: As previously hinted, who can fathom the Oedipal conundrum of being the son of Bob Guccione?

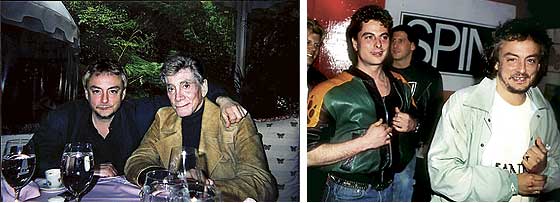

The basic story of the beginning of the Lear-like split in the House of Gooch goes thus: After his initial funding of Spin, Bob Sr. attempted to close the place, demanding all copyrights be turned over to him. Bob Jr. refused, and after rescuing the subscription list from a trash can, relaunched the mag with his own investors. Outraged by this defiance, Bob Sr. closed the iron door on his son, refusing to acknowledge Jr.’s rapprochement attempts. Brother Tony Guccione, likewise excommunicated, said of his father, “It is the Sicilian persona, being able to cut off a limb without remorse.” Beyond acknowledging that “my father can be a very stubborn man,” Bob Jr. does not talk about the fight. Going into rarely exercised Soprano mode, he says, “That’s a family matter.”

Recently, however, as the elder Guccione struggles with debilitating throat cancer, the two have gotten over their differences. The ongoing reconciliation has allowed Bob Jr. to more fully appreciate what he calls “my father’s larger-than-life immigrant epic … from Brooklyn to all that.” One thing Gooch has realized over the years is that “I am a lot like my father, but I never wanted to be him. I mean, how could I? He lived in a special time and ran with it like no one else. But I never wanted to take over Penthouse or live that sort of life.”

The fact that his own existence is pitched on a smaller canvas than his father’s is something Bob Jr., childless after two marriages, has grown to embrace. While Bob Sr.’s 27,000-square-foot, 45-room townhouse on East 67th Street and his $200 million collection of Picassos and Matisses were sold to settle almost inconceivable debts, Bob Jr. is happy enough to move into a two-bedroom apartment in Brooklyn where things are “quiet.” For sure, there will be no $17 million cold-fusion schemes, or anything like that, emerging from the Discover offices.

It’s the Guccione family tao: the sense of mission, the messianic zeal for space exploration, better oral sex, etc.

Bob Jr. says that buying Discover has brought him closer to his father, a contention seemingly borne out by an e-mail received from Bob Sr., currently residing in Palm Springs. Asked to compare Omni with Discover, Guccione wrote, “When I started Omni I tried to make it as reader friendly as possible, adding humor and cartoons to the mix … In my opinion Omni was the best looking and most balanced magazine on the market … Discover is a somewhat different package. It is devoted to a wide variety of more serious matters, although Bobby, in his wisdom, has introduced other, somewhat lighter elements to round it out … I, for one, find myself reading it from cover to cover.”

Assessing his son’s qualities as a publisher, Bob Sr. goes on to say that while “Bobby was always a relentlessly determined young man, a characteristic that we both share,” he is also “very kind and sentimental, which softens the impact of his drive on his staff.”

The letter ends with the elder Gooch saying, “My relationship with Bobby is one of mutual love and respect. Who could ask for more?”

Choked up, Gooch, who, after the Sports Illustrated swimsuit issue outsold Penthouse, advised his father “to put the clothes back on the girls” (a suggestion that was not heeded), says, “In all these years, he’s never told me what he thinks of me as a publisher … It is crazy, pondering all these mysteries of existence when it is so hard to even understand how things work with people you love.”

Then Gooch interrupts himself. He’d been spritzing about one more story he might consider putting in the new Discover: “What do scientists tell their shrinks?”—i.e., is there any place for commonplace neurosis in a life dedicated to casting out myth and delusion “like peeling bark from a tree?” But now a little boy, no more than 4, was running down the planetarium ramp. The boy’s mother, a tourist with a southern accent, was chasing him, which only made the kid run faster, smiling wildly as he wove in and out of the late-morning crowd.

“He’s fearless,” says Gooch, beaming at being one with this brave new cosmos. “He’ll probably grow up to be a scientist.”