Bill Keller, the executive editor of the New York Times, sat on a couch in the Oval Office of the White House, three feet from President George W. Bush, and listened.

For a meeting without historical precedent, the president of the United States had called the Times to the White House to personally try to prevent a state secret from appearing in print—an exposé of the National Security Agency’s efforts to monitor phone calls without court-approved warrants that the Times had held back on for over a year. Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr. sat in a wing chair facing Bush, while Keller and Washington bureau chief Philip Taubman sat across from Bush’s lawyer, Harriet Miers, and national-security adviser Stephen Hadley. General Michael Hayden, the then-director of the National Security Agency, sat alongside Bush with a thick briefing book in his lap.

After stiff pleasantries, Bush issued an emphatic warning: If they revealed the secret program to the public and there was another terrorist attack on American soil, the Paper of Record would be implicated. “The basic message,” recalls Keller, “was, ‘You’ll have blood on your hands.’ ”

The meeting lasted an hour. Afterward, Sulzberger and Keller stood outside the White House. Undaunted by the president’s logic and his threats, Keller told Sulzberger, “Nothing I heard in there changed my mind.” Sulzberger agreed.

Eleven days after the meeting with Bush, the Times defied the president; the story, by James Risen and Eric Lichtblau, was headlined bush lets u.s. spy on callers without courts. That same day, the USA Patriot Act was blocked in the Senate.

The White House went into attack mode. Its target: Bill Keller and the New York Times.

The Times is as powerful a news organization, and media brand, as any on earth, but the cracks in its foundations have become disconcertingly visible. Of course, things could be much worse. A look at the papers in most other cities reveals what the Times might look like in a nightmare future: a bland, cowed publication with ads on its front page, sustained by auto guides and real-estate brochures. The distance between here and there, once comfortably vast, has shortened considerably as the newspaper finds its financial, legal, and journalistic powers under assault. The Times itself helped weaken the right of reporters to protect sources by taking Judith Miller’s tortured case to the steps of the Supreme Court and failing. The paper has been attacked by the president as “disgraceful” for publishing national-security secrets, the vice-president has led a chorus of conservative commentators impugning its patriotism, and a grand-jury probe of the NSA leak could bring yet more subpoenas for reporters. Conservative commentators have even urged the Justice Department to charge the paper under the Espionage Act, an unlikely but terrifying prospect that could mean jail time for Sulzberger and Keller and perhaps force the closure of the newspaper. Ominously, the Bush administration appears to have the support of the public; a national poll shows 54 percent of Americans in favor of wiretapping without warrants. There’s not a lot of enthusiasm for press freedom, either.

Meanwhile, the very business of selling newspapers is falling apart. The Web has gnawed away at the Times’ ad revenue, and as the cost of newsprint soars, the newspaper itself is literally shrinking: Next year, the Times will be 1.5 inches narrower, with 5 percent less space for news (not a huge loss, but a crushing metaphor). Under publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr., whose family has operated the paper since 1896 and maintains majority ownership, the company’s shares have lost half their value since 2002, frustrating not only Wall Street but legions of stock-owning employees. While Sulzberger searches for new sources of revenue in what appears to be an ad hoc manner, he entrusts the editorial power to Bill Keller, who, famously, was not Sulzberger’s first choice to be in charge.

In 2001, in the months leading up to Joe Lelyveld’s retirement as executive editor, the paper’s highest editorial position, the then–editorial-page editor Howell Raines had sold himself to Sulzberger as a revolutionary and painted Lelyveld (and, by association, his protégé Keller) as defending a newsroom full of “lifers, careerists, nerds, time- servers and drones” (this from Raines’s recent memoir). Raines advocated a hyperaggressive news culture, promising the business side of the newspaper that he could produce more bang for the paper’s buck by cracking the whip. Passing over Keller, the managing editor at the time, Sulzberger gave Raines the job. But 21 months into his tenure, when reporter Jayson Blair admitted to faking news stories, Raines had so many enemies at the paper that he couldn’t survive the ensuing scandal.

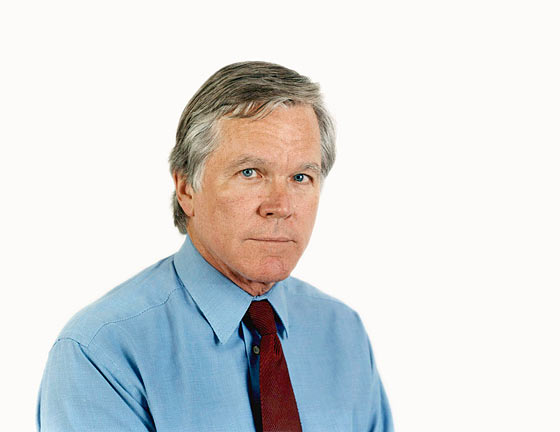

Executive Editor Bill Keller’s major relationships inside the Times.

THE SIDEKICK Not originally close to Keller, Managing Editor Jill Abramson (left) has become the enforcer in the newsroom and is also asserting herself in Washington.

THE OLD FRIEND Keller is under increasing pressure to embolden the paper’s Washington bureau, which, under the leadership of Philip Taubman (center), his pal from their Moscow days, has been considered weak and uneven.

THE BOSS Publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr. (right) and Keller grew closer after enduring the Judy Miller legal mess together. Many in the newsroom believe Keller too easily capitulates to business-side demands.

Photo: Matthew Peyton/Getty Images; Courtesy of Simon and Schuster; Ruby Washington/The New York Times/Redux

So after a two-month return stint by Lelyveld in the spring of 2003, Sulzberger tapped Keller, in a move widely thought to be orchestrated by his mentor. Sulzberger may have been cornered, but the choice restored order to the newsroom. Keller was the anti- Howell, stable and strikingly inoffensive, the beta to Raines’s alpha. In his first speech to the staff, Keller signaled a downshift, urging reporters to spend more time with their families, assuring people close to Raines that they needn’t fear petty reprisals. His primary mode of communication, even with people who sat within sight of his office, was e-mail. Ushering in an era of transparency and nonconfrontation, he dubbed his biannual Q&A sessions with reporters “Throw Things at Bill.” He was surprised to discover just how defeated the newsroom was. In the daily page-one meetings, Keller says, he would “throw something out on the table expecting people to tear it apart, and everybody would wait quietly and look around and wait to hear what I thought. They were expecting me to tell them what the right answer was.”

“I think Howell’s view of leadership is martial, it’s Robert E. Lee, it’s Bear Bryant,” he says. “And mine is more paterfamilias, I guess. You are dependent on this huge reservoir of talent, and your job is to create the circumstances under which they can do their best work, to reward them when they do well, correct them when they do wrong, set some guidelines, and spur their ambitions. But it’s not about me.”

The Keller honeymoon did not last long. In time, more and more members of the notoriously cantankerous newsroom began to find his self-effacement troubling, especially in view of the challenges facing the Times and quality journalism in general. That Keller was committed to safeguarding the paper’s editorial integrity was never doubted; what people started to worry about was whether that was all he could do and whether it would be enough.

Bill Keller, 57, a California native, son of a onetime chief executive of Chevron, is a fiercely intelligent, taciturn, occasionally prickly man who never wanted to be an editor, let alone a leader. But, like Lelyveld, he believes that reporters are the heart of the Times and should run it, even if they have to be torn away from what they do best.

Keller was among the most gifted foreign correspondents of his generation. A graduate of Pomona College, he went to work for the Times in 1984 and, two years later, was sent to Moscow to serve under bureau chief Philip Taubman. His then-wife, Ann Cooper, was a correspondent for National Public Radio, and the two took immediately to Russia. Good fortune struck early. While out with Cooper and Keller, Taubman’s wife, Times reporter Felicity Barringer, suggested they visit dissident intellectual Andrei Sakharov, who was about to return from exile. That very day, the Soviet government had installed a phone in his house so he could receive a call from Mikhail Gorbachev. A guard at the house gave the reporters Sakharov’s number, and they rushed back to the Times bureau.

Normally, a bureau chief might choose to take such a big story for himself, but Taubman let Keller have it. “Phil said, ‘You’ve got the number, you make the call,’” says Keller. “He let me do the share of the stories that were obviously destined for page one.”

In Moscow, Keller worked sixteen-hour days. Among his friends there was David Remnick, then a Washington Post reporter and now editor of The New Yorker. When Remnick arrived in Moscow in 1988, he sized up his chief competitor. “To watch him work, there’s a certain kind of cool intelligence to his bearing,” Remnick says. At Remnick’s first press conference, he noticed that Keller asked no questions and barely took notes. Reading the next day’s paper, he realized Keller had “already been to everybody’s kitchen and sewn the thing up.”

Keller and Remnick had one of the great journalistic opportunities of the twentieth century, witnessing the fall of the Soviet Union, and they both produced spectacular work. Barringer says Keller’s journalism was straighter, Remnick’s more soulful. Taubman compares their competition to “a heavyweight championship match.”

Keller won. He was in Cuba covering Gorbachev’s visit when he learned that he’d won the Pulitzer Prize in 1989. Remnick’s reaction: “I can’t say my initial feelings were ones of overwhelming glee. But he earned it, flat-out.”

Afterward, Keller and Remnick both got book contracts. Remnick’s book, Lenin’s Tomb: The Last Days of the Soviet Empire, was published in 1993 and won a Pulitzer. Keller could never finish his and eventually had to return the advance to the publisher. “I’m still paying it back, actually,” says Keller, “on the installment plan.”

Keller remained in Moscow until 1992, then took over as the Times’ Johannesburg bureau chief to cover the collapse of apartheid. That same year, he and Cooper adopted a Russian child, Tom. Two years later, Lelyveld traveled to South Africa—where he was once bureau chief himself— to sound out Keller about becoming an editor. The two barely knew each other, having met once in Moscow and for lunch another time in London. “He was one of our stars, and I wanted to see if he had any interest,” says Lelyveld, who agreed to be interviewed only about his recruitment of Keller. The two took a road trip together through the Eastern Cape province, “and I kind of orated on the satisfactions of editing and how I hadn’t thought of it myself until late in the game and he should really think about it,” Lelyveld says. “He was completely cold and unresponsive to it.”

The following year, Lelyveld wrote him a letter asking if he’d like to talk about the foreign-editor job. “To my amazement, we didn’t even meet, he accepted the job.”

Keller now describes his rationale for suddenly changing his mind as uncomplicated—foreign editor is a prestigious post, and what could you do after covering the fall of communism and apartheid, anyway?

Moving to New York, Keller wrote one last piece on South Africa, an article for the Times Magazine about Nelson Mandela’s wife, Winnie, in which he cited a book called The Lady: The Life and Times of Winnie Mandela. The following week, the magazine published a letter by the book’s author.

I thoroughly enjoyed Bill Keller’s article “The Anti-Mandela” (May 14) and am glad he found my biography of Winnie Mandela useful. I agree with him that the phrase “a blistering inferno of racial hatred,” used to describe her childhood, is an overwrought one. However, credit where credit is due. It is not my phrase, it is Winnie’s own.

— Emma Gilbey, Sag Harbor, L.I.

After reading the letter, Keller called Gilbey, a British journalist living in New York, and asked her to coffee at the Times cafeteria. Gilbey, at the time, had a reputation as something of a power-dater; her exes included Senator John Kerry and Pink Floyd guitarist David Gilmour. An affair ensued, which shocked Keller’s friends. “I felt bad for everyone involved,” says Stephen Engelberg, a former Times reporter. “This was not characteristic behavior at all. I wouldn’t pretend to be Bill’s psychologist, but he didn’t get a red sports car, so …”

Gilbey offers another explanation, related to Keller’s son. “After he fell in love with Tom, he was just falling in love all over the place—with chairs and tables—and when he fell in love with me he didn’t know whether this was actually real or whether he actually loved me or was in love with the world. And, so, you know, we sort of thank Tom.”

Two years after they met, Gilbey was pregnant, Keller was divorced from Cooper, and he had a new job as managing editor under Joe Lelyveld.

On a morning in late July, Keller met me at La Guardia airport to catch a shuttle flight to Washington, D.C., where he was to visit the paper’s bureau. Among a crowd of executives drinking coffee and perusing the newspapers, Keller was barely noticed—except by women. With his square jaw, patrician nose, and crinkly eyes, he has the look of a handsome doctor on a soap opera. Onboard the plane, an attractive older woman gazed across the aisle at him while her husband punched e-mail messages on his Treo. Keller didn’t seem to notice.

“You asked once before whether I considered myself ambitious,” he told me, “and I don’t in the sense that I really aspired to the jobs that I got. But I am competitive.”

Keller’s wife says he’s got a bigger ego than he lets on, suggesting his ostentatious humility is a costume. She calls him an “alpha male in disguise.”

The alpha-beta question is at the heart of any evaluation of Keller’s tenure as executive editor. He was, after all, hired to be a kind of institutional nurturer, which turned out to be an untenable role. It took him ten months to even address the question of whether the paper needed to make amends for Judith Miller’s discredited stories on Iraq’s illusory weapons of mass destruction, which had been published under Raines. By that time, it was clear that Miller had, at best, been led astray by unreliable sources and that there were serious problems with her reporting. At that point, Keller gathered his top lieutenants, including Managing Editor Jill Abramson, and asked them how far the paper ought to go in investigating those stories. The consensus that emerged was that the paper should not pursue an internal review on the scale of what had been done following Jayson Blair because it would be too damaging for a newsroom still recovering from that scandal. Keller, who was inclined to make recovery his top priority, agreed.

Shortly thereafter, prompted by public editor Daniel Okrent’s decision to write a column about Miller’s WMD stories, the paper published an editor’s note in May 2004. Keller later acknowledged that it came too late, apologizing in a memo for mistakes in the Miller episode: “I wish we had dealt with the controversy over our coverage of WMD as soon as I became executive editor … I was trying to get my arms around a huge new job, appoint my team, get the paper fully back to normal and I feared the WMD issue could become a crippling distraction.”

Keller’s reluctance to engage the issue, for which he was clobbered by bloggers in particular, had the effect of solidifying a reputation for indecisiveness that had started to gel, in part, as a function of his allowing Abramson to have the greater profile in the newsroom. Spending most of his time in front of a computer screen, he managed in a hands-off style that allowed self-starting editors to prosper but that sidestepped hard calls. “By avoiding strife, he allowed problems to fester,” observes one Times reporter who, like others quoted in this story, requested anonymity for fear of angering his colleagues and/or bosses. “And they seem to have a nasty habit of blowing up.”

Other than Sulzberger, Abramson is Keller’s most important and complicated relationship at the paper. Because she had worked mostly in Washington, Keller didn’t know her well when she was appointed the managing editor for news (John Geddes is the managing editor for operations). Keller had preferred to make former metro editor Jon Landman his news managing editor but offered the post to Abramson as a concession to Sulzberger, who wants Abramson in contention to be the Times’ first female executive editor.

The 52-year-old Abramson arrived at the paper as a reporter in 1997 after a decade at The Wall Street Journal. She marched quickly through the ranks, keeping close company with other powerful women writers, including Maureen Dowd. In right-wing conspiracies about the Times, Abramson and Dowd are seen as a liberal female cabal with occult power over the relatively benign and more conservative Keller. Abramson is known within the paper for her sharp elbows and for being an aggressive editor who implores reporters to “go kill for us.” Indeed, Abramson advertises herself as the more assertive of Keller’s consiglieri. “I’m blunter and more impatient, and I tend to worry and think things are off course,” she says. “And he’s more programmed the other way.”

During our interviews, Keller repeatedly referred to Abramson as “my sidekick.” He describes his relationship to Abramson as being like a marriage, with all its attendant complexities. “It’s harder to see straight when you’re in it,” says Keller. “Like any marriage, we have our occasional spats.”

Before Keller became editor, Abramson wasn’t necessarily his greatest fan. One Timesman recalls Abramson characterizing him as aloof, arrogant, and “incommunicado.” After he offered her the job, Abramson pushed for her friend and former deputy Rick Berke to succeed her as bureau chief. Instead, Keller went with his trusted friend from Moscow, Philip Taubman. “Rick had been not only a steady, wonderful deputy but someone who also kept morale in the bureau up,” Abramson says. “I thought he would have been a good choice.”

Keller divides his executive editorship thus far into two distinct chapters: the period of healing after Raines left and the “period of distractions,” when he found himself once again tormented by Judy Miller, who this time was fighting a federal subpoena in the Valerie Plame leak case. The year-and-a-half-long ordeal—which Abramson calls an “icky, demoralized time”—cemented the relationship between Abramson and Keller. “Judy Miller was our first bonding experience,” he says.

“If Abe was running the New York Times today,” says Keller, he would find himself “in the same predicament that I find myself in … Howell may have been the last gasp of the thunderbolt editor.”

The impact of the Miller affair on the paper’s reputation was enormous—in many ways, more damaging than the Blair scandal. The Times spent more than $1.5 million and an incalculable amount of public credibility defending a reporter who appeared to many to be cooperating with a White House effort to smear a WMD whistle-blower.

The case was byzantine, but it basically revolved around relationships—Sulzberger’s to Keller, Keller’s to Abramson, and everybody’s to Miller. Keller, though, had a strangely detached role in it all. While Sulzberger went on his crusade to make Miller a martyr for freedom of the press and Abramson got caught up in the day-to-day dogfight of holding together the Washington bureau (where resentment against Miller and Times management was running very hot), Keller seemed to float above the fray. He did make one critical decision, though; when Miller tried to claim that Abramson had known about her reporting on the Plame case, Abramson said Miller was lying. That made it Miller’s word against Abramson’s, and Keller sided with his managing editor. “I’m pretty sure Jill would have remembered,” he says, “and I’m pretty sure Judy would have put it in writing anyway.” Even before Miller went to jail for 85 days to protect her source, Abramson and Keller decided she would never write for the paper again.

Keller then did something that angered even his supporters at the Times. As Miller’s controversial role in the case leaked out in the press, Keller took off on a preplanned twelve-day trip to the paper’s Asia bureaus. He was under intense pressure, and it was viewed by some as a convenient escape from the turmoil at home. “It was absolutely fucking awful,” recalls Gilbey, who was traveling with him. “If he had come back because of Judy—what message are you sending to the foreign desk as opposed to the Washington desk? If it had been, ‘I’ve got this one lunatic at home and I’m not coming …’ The Times has, like, a million children—well, actually only 1,200 fucking children—and they got left behind at home.”

I asked her if perhaps there wasn’t a streak of conflict avoidance in Keller. “Well,” she says, “nobody likes conflict.”

As with Sulzberger, whose father oversaw business and editorial revolutions at the paper in the early seventies, the New York Times’ burdensome history hangs over Keller’s every move. In June, when the Times celebrated the 35th anniversary of the Supreme Court decision that allowed it to publish a top-secret government file regarding the faltering war in Vietnam, Jill Abramson led a panel discussion in Washington. She told the audience that the NSA story “may very well turn out to be this generation’s Pentagon Papers” and recalled A. M. Rosenthal, the legendary executive editor of the Times who published the story and died in May, as an aggressive hero of journalism, “a gutsy, larger-than-life character, an editor perfectly matched to the historic moment.”

Was Bill Keller also a man perfectly matched to his historic moment? When I ask her this question, Abramson pauses. “I want to think about it,” she says. Not because she doubts it, she emphasizes, but because she wants to draw up the perfect response.

Sitting next to Abramson at the Pentagon Papers panel was reporter James Risen. In the fall of 2004, Risen had brought a massive scoop to his editors: Beginning in the days after September 11, he discovered, the Bush administration had authorized the National Security Agency to eavesdrop on foreign calls into the United States without court-approved warrants.

When the Times first approached the White House with the story that fall, Taubman took the lead editorial role, beginning a series of meetings with Bush officials. General Hayden, the NSA director, took him on a personal tour of the agency’s headquarters and tried to impress upon him the importance of its secret programs. Taubman also met personally with then–national-security adviser Condoleezza Rice, a close friend of his for more than twenty years. Six months before the 2004 election, Taubman had thrown a lavish dinner party for Rice at his house in Washington.

Shortly after Taubman was briefed by the Bush administration, Keller himself met with Rice, Hayden, and others. “I think they were shocked they were having to share this with journalists,” Keller recalls. But, sitting on a potentially explosive piece of news that could tip the presidential election to John Kerry, Keller was persuaded by the administration’s counterarguments and decided against publishing Risen’s revelations.

Asked recently if there was a defining piece of evidence that affected his decision to hold the story then, Keller said no, then took a deep breath and added, “The argument they made was that, even though it may seem obvious to us that they’re going to try to eavesdrop on terrorists’ phone calls, the behavior of terrorists suggested that it wasn’t obvious to them. Therefore, publishing the story would change their behavior.”

In a long, explanatory e-mail he sent me, Keller says the issue of the legality of the NSA program had not been the thrust of the original story—at least, not that he recalls. “Perhaps [the legality of the wiretaps] should have struck me earlier, perhaps it was clear to the reporters,” he writes. “In its original incarnation, I saw it as essentially a story about the methodology of counter terrorism.” In other words, Keller maintains that he did not originally grasp what the reporters considered the essence of their scoop.

The fact that the Times was suffering from a profound lack of institutional confidence also contributed to the decision to hold the story. On October 25, 2004, the Times reported on unsecured munitions left after the invasion of Iraq and was promptly slammed by the Bush administration, which vigorously questioned the story’s accuracy and scared editors so bad that Abramson worried she was going to be the next Mary Mapes, the producer of the flawed CBS News report on Bush’s National Guard service. When a Minnesota TV station broadcast video that proved the munitions story, Keller told a friend, “Thank God for that.”

The holding of the NSA story enraged both Risen and Lichtblau, who primarily blamed Taubman. Risen would not comment for this story, but colleagues say he told them that Taubman lacked the “balls” to publish his scoop. Both Risen and Lichtblau—as well as many other reporters in the Washington bureau—suspected Taubman’s deference to Hayden and Rice had influenced his decision and thus Keller’s. Asked about this, Keller calls it a “bum rap” and says it was his own decision to make, not Taubman’s. “The idea that he’s somehow pulling his punches to accommodate sources is just wrong,” says Keller. “I know where that’s coming from, but the decision not to publish the story early was mine. There was nobody above the rank of reporter who was arguing that we should publish it.”

Risen was beyond furious. A 51-year-old reporter who could be cranky and uncommunicative, he had clashed with his superiors on major stories before, including the Wen Ho Lee case, which concerned the Chinese scientist accused of stealing nuclear secrets from Los Alamos National Laboratory (Keller, then the managing editor, had written an editor’s note disavowing some of Risen’s reporting). In addition, Risen harbored lingering resentment of Abramson over the paper’s WMD coverage. When she was Washington bureau chief under Raines, Risen has claimed to at least two people, he offered her reporting that cast doubt on the Bush administration’s evidence about Iraq’s WMD program. At the time, Miller’s reporting was how the Times, as an extension of Raines, saw the subject. And Abramson felt powerless to fight Raines over this and other things. When Risen pressed his case, she finally told him to “get with the program,” these people say.

Abramson, a known Raines antagonist, declined to comment on that particular encounter, but in an earlier interview described the climate she was working under. “I really felt like I had barely been able to do the job, because in the Howell regime, all three of the top editors all thought they knew best about Washington,” says Abramson, “and a lot of days, I didn’t necessarily feel like I was really the bureau chief.”

(Raines, in an e-mail, responds: “If Jill skewed or suppressed stories from Jim Risen or anyone else she did so on her own hook, not as a result of any instruction or signal from me. It was a point of tension between Jill and me that we were consistently behind on weapons and intelligence stories.”)

On the NSA story, Risen called Abramson the weekend before the election, begging her to convince Keller to run it. Abramson says she “anguished” over it, eventually siding with Keller and Taubman.

For Risen, holding the NSA spying story was the final insult. After the 2004 election, communications between him and Keller’s two key advisers—Abramson and Taubman—effectively disintegrated. “There was no working relationship between Risen and Jill, or Risen and Phil,” says a Times person who knows Risen well. “They didn’t engage him.”

The story, of course, didn’t go away. The Times could have published it right after the election. Keller offers a curious explanation for why that didn’t happen, suggesting that the “normal process was much delayed because the lead reporter on the story went on a book leave,” as if he had disappeared off the face of the earth. According to several sources, Risen was convinced that the paper would never publish the story, and he had already signed a lucrative deal with the Free Press for a book that was originally to be about George Tenet and the CIA. According to one Times person, Risen said he’d quit if the paper didn’t allow him the leave of absence, and off he went to write his book.

In the summer of 2005, two months after Risen returned from book leave, Taubman learned from a friend of Risen’s that he planned on including a chapter in his book about the NSA eavesdropping program. Both Abramson and Taubman confronted Risen, separately, and asked him point-blank whether he was using the material for his book. People briefed on those meetings say he was “evasive” and “squirrelly.”

Privately, the editors believed that Risen, who wasn’t able to get Tenet to cooperate because he had his own book deal, was desperate to salvage his book and had used the NSA material to pad it out. Taubman was livid, telling Risen that it was against Times policy to use material obtained on the newspaper’s dime for his book without notifying the paper.

In September, shortly after his conversation with Taubman, Risen delivered the manuscript to the Free Press, including a chapter called “The Program,” detailing the government’s secret eavesdropping program and drawn from the original draft of the story Risen had filed to the Times the year before. The Free Press believed it now owned the material (and, in a comic twist, offered the Times first-serial rights).

As the book’s publication loomed in the near distance (the Free Press was cagey about when exactly it would come out), Risen went back to work on the story for the Times. He was now caught between two obligations, but the Times was in an even tougher spot: If Keller again folded under the weight of White House arguments and held the story, the Times would be humiliated by Risen’s book. In a long e-mail about the origins of the spying story, Keller was adamant that the book had not been the “deciding factor” in publishing. The “conventional wisdom” that Risen’s book forced the paper to publish the story, he writes, “is bullshit.”

But he also admits, “I have tried to be careful never to say the Risen book was irrelevant. I’ve said it was a factor in reopening the discussion.” (In fact, Keller has never said that publicly before.)

According to Keller, the additional reporting in the fall of 2005 improved the story, with more people inside the government questioning the legal basis for the program. The argument over the iffy legality had grown starker, says Keller, and the fear that the Times might be relying entirely on the word of a partisan ax-grinder (which, according to sources, was originally the case) was now assuaged. As Keller wrote in an e-mail to me this summer, which he also sent to Times public editor Byron Calame, “We now had some new people who could in no way be characterized as disgruntled bureaucrats or war-on-terror doves saying we should publish. That was a big deal.”

Colleagues describe Risen and Lichtblau as vehement that the story okayed in 2005 was not fundamentally different from the one that had been rejected in 2004.

After his meeting at the White House, Keller sought out the counsel of Joe Lelyveld, whom he hadn’t spoken to in months. They had coffee together on the Upper East Side near Lelyveld’s apartment. There, Lelyveld advised Keller to publish but also not to overplay it with a big headline on page one.

On the evening of December 15, Keller called the White House to inform Bush’s aides that the NSA story was about to go up on the Times Website and that it would appear in the newspaper the next day. Two days later, Russell Tice, a former NSA intelligence analyst, requested permission to testify to Congress about his doubts about the legality of the NSA program, prompting speculation that he was a source for the Times. He has since been subpoenaed by a grand jury seeking to indict whoever leaked the story to the Times. If the prosecution requires more evidence, it could issue subpoenas to Risen and Lichtblau, prompting another legal war over the protection of sources. The Times has retained two law firms to prepare for this possibility.

Keller will never be accused of under-thinking a problem. In one of our many conversations about the NSA story, he offered a highly unusual rationale for why it took fourteen months for the story to find its way into the paper: “There was an erosion of the administration’s credibility, not just with us, but with the public,” he said, “as more and more was revealed—including in the Times, by the way—about the use of intelligence in the run-up to the war.

“As time passed,” he added, “they’ve demonstrated that they’re entitled to somewhat less benefit of the doubt.”

The effect on Keller of publishing the NSA story was clear. A month later, I saw him at a cocktail party—a rare appearance for a man whose wife calls him “socially autistic”—and needled him about when, in the spirit of transparency, we could expect to be told why the paper had held the NSA story for more than a year before publishing it. That same month, Calame had been stonewalled by Keller on the issue.

“We’re done with transparency for a while,” Keller told me, with a just-perceptible smirk.

Keller now says it surprises him that other stories the paper ran didn’t have the same effect as the NSA story. He thinks the Times’ debunking of the Iraqi aluminum tubes, once thought to be proof of a nuclear program, was equally powerful. “There were a number of stories where I thought people would say, ‘Yeah, the New York Times, that’s right.’ The NSA happened to be that story, but there were a bunch of things before that I thought would be that story,” he says.

The power of the New York Times has always been tied to how it covers the biggest story in the land: the White House. The spying scoop seemed to remind Keller that Washington coverage was where the Times would be historically measured. But accepting it and liking it are two different things. The NSA story “certainly drove home the point that the Washington bureau is the paper’s megaphone,” he says. “And because Washington is Washington, it tends to be what you’ll be judged by. It’s not necessarily what I’d want the paper to be judged by.”

Keller enjoyed a brief alpha moment after the NSA story was published. “The story freed Bill Keller to be Bill Keller,” says Okrent, the former public editor. The boost to morale at the paper was unquestionable. Reporter Gardiner Harris voices the sentiment of many in the Washington bureau: “The yearlong delay was a transitional moment for Bill,” he says. “The delay resulted from his timidity. I’m not at all convinced that it was a change in his mind-set that led it to be published.” But, he adds, “once published, it sent him down a path to being more aggressive.”

But almost as quickly, Keller was attacked again from outside the paper, mostly by the left, for delaying the story and possibly costing Kerry the election.

In January, Keller and Abramson flew to Washington to discuss overhauling the Washington bureau. They wanted fewer incremental stories on the daily political scrum, more “high impact” stories like the NSA scoop. “Clearly, the NSA story and the way it lifted the whole paper was a big factor in setting that as a priority,” says Keller.

The changes were a long time coming. Late in 2003, six months into Keller’s editorship, at least three senior reporters at the paper told Keller they thought the paper’s coverage of the Bush administration was weak and frightened. Keller tended to bristle at such criticism. But Abramson says the Abu Ghraib prison torture story, broken by CBS News and The New Yorker, showed that the Times had fallen behind.

Keller’s wife says he’s got a bigger ego than he lets on. She calls him an “alpha male in disguise.”

Keller now admits that the paper’s Washington bureau had, until late last year, been too “reactive” to news, often playing catch-up on big stories broken by others. Asked if the need for a shake-up was an implicit criticism of his friend Taubman, Keller pauses for a long moment, then declines to answer directly. “A number of things, including the NSA story, awakened us to the potential that wasn’t being fully realized in the bureau,” he says.

But enacting change turned out to be harder than Keller had imagined. Inside the Times, there was a growing consensus that Taubman was too cautious, and Keller himself thought the bureau needed fresh blood. Just as the NSA story was being revived in the fall of 2005, Abramson, who had begun to take a larger role in Washington coverage, suggested that 42-year-old Don Van Natta Jr., a Pulitzer Prize–winning reporter, be promoted to Taubman’s deputy, the No. 2 slot, and in November 2005, Keller offered Van Natta that job. This move was perceived by some as an attempt to undermine Taubman, just as Raines had done to Abramson years ago when he assigned a relatively inexperienced reporter named Patrick Tyler to be her No. 2. (“She’s got a little bit of Howell in her,” notes one Times reporter of Abramson.)

But Taubman would not let that happen to him. A week after Keller offered Van Natta the job, Taubman met with Van Natta and told him there’d be two deputy positions. Later, Taubman would propose a three-deputy configuration.

Weighing the diminishing job against a $1 million advance he and Jeff Gerth had been offered to co-write a book about Hillary Clinton, Van Natta reversed course and turned down Keller. The apparent power struggle between Abramson and Taubman—or at least Keller’s inability to square his relationships—had effectively blown up Keller’s best idea for recharging the D.C. bureau, without removing Taubman. Keller was incensed—at Van Natta. “Yeah, I was mad that he didn’t take the job,” says Keller. “We were serious about wanting to move the bureau away from incremental coverage to high-impact coverage, and he would be there supporting that, and I guess I took his decision not to take the job as at least in part a lack of trust or a lack of faith in us.”

The difficulty of navigating the paper through this historic period can hardly be overstated. The Bush administration has masterfully eroded the press’s ability to do its job. Partisan bloggers and radio commentators scrutinize every story for evidence of carrying somebody’s political water. For a paper that aspires to objectivity, like the Times, and for an editor who is a true centrist, like Keller, that has made the going very tough.

After the NSA story, Keller allowed the paper to become more aggressive in its coverage of the administration, leading in June to Risen’s Swift banking story, about the Bush administration’s efforts to track international financial records. This time, the backlash was even harsher. If the White House had simply been infuriated by the first report on a secret program, it went ballistic this time, excoriating the Times and inspiring bloggers and talk-radio hosts to call for Keller’s head. One commentator suggested he be gassed. The vice-president said it was “disturbing” that “the news media take it upon themselves to disclose vital national-security programs.”

In some ways, the Swift story was a stumble for the Times. In an effort to unleash another NSA-size story by giving Risen (now a Pulitzer Prize winner for his NSA story) room to run, Keller appeared to overplay the paper’s hand. After all, this program not only was legal but also had been disclosed in a United Nations report in 2002 and even alluded to by Bush himself in less- specific ways. If the paper had not framed the story as a blockbuster scoop, it might have avoided some of the backlash.

Keller, though, was uncharacteristically fired up by the effort to tar him. “They pissed me off,” he says. “I think the administration is genuinely distressed that we ran the story over their objections. I think they were embarrassed by it, by the fact that this most secretive of administrations has so much trouble keeping its secrets. I think they were probably sincere in their anxiety that publicizing this program might jeopardize it. And, you know, that’s all fair, but when they stir up a partisan hatefest and impugn your integrity and patriotism, that is, to borrow a word from the White House list of talking points, disgraceful.”

If Keller had been vague and unsteady in defending the eavesdropping story, he moved decisively to ward off this next wave of attacks from the Bush administration. He took to the television and the op-ed page and fired back at his critics. It wasn’t necessarily a great performance—he looked hunched and defensive on CBS News’ Face the Nation—but his critics gave him points for letting his alpha flag fly.

Is Bill Keller “an editor perfectly matched to the historic moment”?

After two weeks of no response, I e-mailed Abramson and she finally wrote back, “I do think he is very well suited to these times. He is cerebral and careful, which at a historic moment when The New York Times is under such constant scrutiny and attack, serves the paper extremely well. He is gutsy. I’ve watched him stand up and make the tough—and right—call and then fight for and defend his stand, whether involving stories or issues inside the paper.”

To fully answer the historical question about Keller, though, means engaging the subject of his relationship with Arthur Sulzberger and the business aspects of the newspaper. Sulzberger has long wrestled with how the Times can prosper, or even survive, in the fast-changing media environment, and for his troubles, he has been battered in the press (Ken Auletta last year in The New Yorker, Michael Wolff more recently in Vanity Fair) as well as savaged in his own newsroom. His championing of Judy Miller, a figure perhaps more reviled within the Times than even Howell Raines, may have been the final straw. Now that the paper’s much-vaunted national circulation strategy has hit a wall, the worry that Sulzberger carries around with him every day is that the Internet is killing his bottom line. The newspaper’s Website simply cannot produce enough revenue to sustain a huge news-gathering operation, and that has put Sulzberger on a tireless quest to cut costs and find the big idea that will save the day. (His investment in the Discovery Channel didn’t do it, nor did the Times’ semi-hostile takeover of the International Herald Tribune. His purchase of About .com has fared better.)

One of Sulzberger’s big ideas was naming Raines executive editor, and when that came crashing down and he was essentially forced to appoint Keller, Sulzberger made sure to curtail his powers. “The person who truly controls the fate of the paper is Arthur Sulzberger,” says one Times staffer, “and in that sense no one feels like they’re in good hands because people feel he’s an incredible boob.”

People who know both men say that their relationship remains scarred by Sulzberger’s initial rejection of Keller and that their interactions still tend to be awkward. But the public floggings that Sulzberger has endured over the Miller affair have softened Keller’s position toward his publisher, leading, says Keller, to “a greater degree of understanding and candor between the two of us.”

Keller depends on Sulzberger to protect the paper from Wall Street—but no one can protect Keller from Sulzberger. Keller meets with him three times a week to discuss business at the paper, a part of the job he loathes. Pressure on the Times has grown in the last year to add more style and entertainment editorial—from Thursday “Styles” to the array of T magazines—while trimming the core news operation. Some changes have been particularly unpopular internally, like the imminent shrinking of the paper size and the “strip ads” that began to appear on section fronts. Keller concedes they are “a blight,” but they are now a fixture.

In the past, Times editors have led revolts against the publisher over newsroom cuts. Now changes are frequently handed to Keller from the business side with little room for negotiation. Asked if he has less power than previous editors to resist the business forces at the paper, Keller says, “Sure, of course,” adding, however, that “it hasn’t really yet been tested. I haven’t been asked to do something I feel would seriously impair my ability to put out a great newspaper.” He says new economic realities require a less adversarial role with the publisher, and that “if Abe was running the New York Times today,” he would find himself “in the same predicament that I find myself in.” For the same reasons, he says, “Howell may have been the last gasp of the thunderbolt school of editor.”

Though Keller took over as executive editor to the great relief of the Times’ old guard, many of these people have begun to privately express frustration with Keller’s passivity. Even Lelyveld is said by friends to be critical of Keller’s job performance.

There is a collective belief that this is precisely the moment for a thunderbolt editor, perhaps even one like the venerated-on-his-passing Rosenthal, who saved the paper in another troubling time by marrying aggressive journalism with a vision for a four-section paper to attract lifestyle advertising that could pay for the reporting. No such vision is apparent now—the newspaper still runs outstanding journalism, but lacks an evident blueprint for the future, or even a leader committed to devising one.

Keller understands the perception and seems committed to changing it, even if it means undergoing something of a personality transplant. “I’ve come to realize, as much as I would like to think of the New York Times as a collective endeavor, at least in the public eye, a lot comes down to me,” he says. “And whether it’s caution or deliberation or a kind of instinct to avoid snap judgment, whatever that characteristic is in me, I think it may have been brought to the fore or exaggerated a bit by my determination not to be Howell in the early days.”

It’s a confession that Keller almost seems to choke on: “You know, over time, I’ve come to realize that, whether I like it or not, to some extent, it has to be about me.”

An optimist might say that if Keller has found his legs, perhaps the newspaper has, too. There are a few of those out there—Jack Shafer, media critic for Slate, says, “I can’t think of a better guy than Bill Keller to have at the top of the paper.” Investigative reporter David Barstow says, “Look, when you’re sailing through a shit storm, it really helps if the captain is steady and strong. You know, our ship may be leaking, but we ain’t going to go under on his watch.”

Where Keller and the paper are heading, though, remains anybody’s guess. With the daily financial pressures and arrows pointed his way, the exit is always a temptation. “Look, this is not what I went into newspapers to do,” he says in a long e-mail discussing the business challenges. “I’m a reporter at heart. I still regard my quality time as the time I spend with reporters and editors, and with stories. (Every time I send someone off to a new reporting assignment, there’s a little voice in my head that says, ‘Take me with you!’)”