I moved to New York City a mere six months ago, expecting an anonymous existence while I struggled to make new friends. Things moved quickly, starting with my very first night out.

“I know you,” said some scruffy guy who accosted me at the Magician, that Lower East Side bar overfrequented by bloggers. “You’re the guy who Garrison Keillor tried to sue.”

That happens to be true. A few years back I launched a T-shirt line with ironic slogans. One parodic shirt in particular apparently raised the ire of the Lake Wobegon creator: “Prairie Ho Companion.” It seemed funny to me, but a micro-scandal ensued when the cease-and-desist for trademark infringement arrived from Keillor’s lawyer. It created a silly blip on the Internet that day, followed by a couple of afternoons of online mayhem, as the story was picked up by Drudge, then Sullivan, then Kos, then Huffington. And then the mainstream media started to call.

My blog was suddenly, and briefly, a big deal.

This isn’t rare. Many people have had moments like this, to greater or lesser degrees. Maybe your college band had a surprise radio hit, or your random blog comment launched a New York Times feature story, or you became a contestant on a reality show about bachelorhood, or you accidentally married Charlie Sheen.

Whatever it was, it wasn’t exactly fame. It was more like microfame. But though I was content to let the moment pass, countless other people are trying to manufacture microfame, over and over again, to various ends—be it a book deal, a reality show, or just the simple ego gratification of having a lot of Facebook friends.

It’s easy to be cynical about this new class of celebrity. The lines between empowerment and self-promotion, between sharing and oversharing, between community and cliques, can be blurry. You can judge for yourself whether the following microcelebs represent naked ambition, talent justly discovered, or genius marketing. The point is that renown is no longer the exclusive province of a select few. Nano-celebrity is there for the taking, if you really want it.

The Networked Celebrity

When we say “microfamous,” our inclination is to imagine a smaller form of celebrity, a lower life-form striving to become a mammal—the macrofamous or suprafamous, perhaps. But microfame is its own distinct species of celebrity, one in which both the subject and the “fans” participate directly in the celebrity’s creation. Microfame extends beyond a creator’s body of work to include a community that leaves comments, publishes reaction videos, sends e-mails, and builds Internet reputations with links.

Where traditional fame was steeped in class envy on the part of the audience and alienation on the part of the celebrity, microfame closes the gap between devotee and celebrity. It feels like a step toward equality. You can become Facebook friends with the microfamous; you can start IM sessions with them. You can love them and hate them at much closer proximity. And you can just as easily begin to cultivate your own set of admirers. Though an element of luck often plays a role in achieving traditional fame, microfame is practically a science. It is attainable like running a marathon or acing the LSAT. All you need is a road map.

Step No. 1: Self-publish.

Once upon a time, aspiring fame seekers had to develop their talents, work hard, and hope to build an audience or be discovered by a power broker. Microfame, however, thrives on the simplicity of online publishing. Now, when anyone can write a blog post or upload a video within minutes, the act of creation is an instance of media exposure in itself.

Adam Bahner was a 25-year-old American Studies doctoral candidate at the University of Minnesota when he started using his booming baritone, which sounded like James Earl Jones recording a soda commercial, to sing strange groove pop in his bedroom. But rather than just release the tracks as MP3 files, he videotaped himself singing the songs, which just added to the weirdness, as the guy is rather petite. About 20 million YouTube views later, you know Bahner as Tay Zonday, the deep-throated singer of “Chocolate Rain.”

My line of parodic T-shirts got me a lawsuit. Zonday, on the other hand, got a call from Dr. Pepper, which asked him to record a spinoff, “Chocolate Cherry Rain.” It garnered him another 4.5 million views on YouTube and a sizable amount of cash.

Microfame has no birthright. Although it is sometimes random, it’s still an earned achievement, either through idiosyncratic talent like Zonday’s or, as we’ll see, media manipulation.

Step No. 2: Stylize.

This egalitarianism poses a downside for the microfamer: There’s fierce competition for the audience’s attention. When celebrity is reproduced like Ikea silverware, being creative isn’t enough. You need to separate yourself from the cacophony by being a little weird. Scratch that—really weird.

In 2006, at the moment when YouTube was becoming dominant, the nascent art of video-blogging was suffering a crisis. A certain hackneyed style had become pervasive: Sit in front of the camera, talk like a newscaster, and throw in some retrograde editing. The medium had already begun to look played out.

Ze Frank struck microfame gold when he launched “The Show,” his stylized take on the video blog. The episode about MySpace pages is typical: It introduces a cultural meme (ugly personal pages), proposes a new way to talk about it (an ugliness contest), and then quickly subverts itself with an intellectual discussion of the topic (ugliness as a democratizing force for artists). Ze’s idiosyncratic style of close-ups, fast edits, and a dumb-smart pop philosophy eventually developed a strong cult following. The audience was large enough for him to introduce his own personal sponsorship platform in which fans could buy something called “duckies,” icons with personalized messages. When duckies started to fill the page, some quick math showed that Ze was making upwards of $1,500 per day.

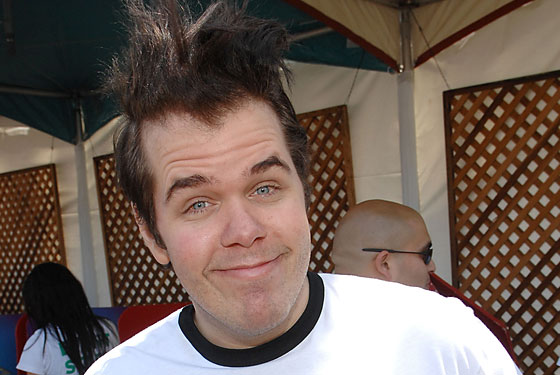

Developing a definitive style might sound daunting, but there are myriad ways to go about it. Just remember that Ana Marie Cox did it by mashing ass fucking with politics, while Perez Hilton drew cocaine scribbles on celebrities’ faces.

Clearly many styles remain to be perfected.

Step No. 3: Overshare.

Now you’ve got a vision and an audience—you’re getting noticed! The next step is to create a thorough archive.

Thankfully, a new set of online tools has emerged to document the minutiae of life even more intensely than traditional blogging platforms. Extremely simple and fast to use, sites like Twitter and Tumblr have enabled the nano-broadcast: clever observations and ripostes targeted at dozens of adoring fans/friends. The dirty little conceit of so many social-media and -networking sites, including Facebook and Flickr and FriendFeed, is that they disguise self-publicity and oversharing as chatting with friends and uploading for storage. By turning private information into public fodder, these sites eliminate the difference between communication and publishing.

The Jedi Knight of the oversharing craft is Julia Allison. A small part of her genius is looking famous without being famous (a touchstone of microfame) by constantly telling her audience what she might be doing at any given moment. If you can admit to perusing her Tumblr or Twitter, you’ll see round-the-clock social updates and photos documenting her diurnal travails.

Allison is a master of a genre I’ll call fauxparazzi—taking photos of non-famous people staged to look famous. The gifted microfamer borrows from the paparazzo’s handbook by choreographing photos that look accidental but are actually snapped from the perfect angle and with the perfect company. Allison’s acts of assisted self-portraiture include Julia in pink taffeta on her disheveled floor, Julia en route to dining with Emily Gould, and Julia at a bachelorette party—all normal events shot with fauxparazzi flair. These photos help “prove” the existence of her stardom.

If all this sounds narcissistic, there are alternatives, the best of which is simply having friends post and tag photos of you on Flickr and Facebook.

This step can be outsourced.

Step No. 4: Respond.

If there is a Latin phrase for “reply to everything,” it should be crocheted on your pillows and tacked above your door. Anytime your name is used, you are required to e-mail, comment, or firebomb the person invoking it. When in doubt, remember these three maxims: There is no such thing as being above the fray, every battle is worth fighting, and all disputes are good press.

Microfame is a game whose victors are contrarians. Choosing the right adversary is your most important move.

Which brings us to Tricia Walsh-Smith, a self-described YouTube star and divorcée who posted a rant about her rich, impotent husband that has reached millions of people. But more important to her longevity, Walsh-Smith’s wide-eyed diatribe triggered a whole community to post reaction videos. First there was a wave of reactions denouncing her as crazy, followed by a second wave of responses coming to her rescue. (Jimmy Kimmel’s monologue about Walsh-Smith was itself a reaction video of sorts.) This is why reaction videos are Internet gold: They create more reaction videos.

The “2 Girls 1 Cup” video is the quintessence of the phenomenon. There’s no need to link to the original video; just imagine the most disgusting, perverse, depraved sexual acts—and then imagine showing them to your friends. This predilection led to a special type of reaction video, in which one person tapes other people watching and reacting to the video. (To illustrate, my two favorite reaction vids: The Roots and Kermit the Frog.) In its own disturbed way, the “2 Girls 1 Cup” phenomenon is the perfection of Fame 2.0, where the ecology of reactions becomes the actual product, more compelling than the original.

As proven by Chris Crocker, the effeminate YouTuber who racked up 20 million views by screaming “Leave Britney alone,” the masters of microfame are strategists who choose precise moments to react.

Step No. 5: Ally.

When you become famous to a small group of people, they think they know enough to gossip about you.

Of course you need to control this conversation, but you can’t possibly be everywhere to manage it, so a close circle of friends becomes absolutely necessary. From anonymous blog comments to frothy bar conversations, confidantes are needed to tout your reputation at every opportunity.

You need a posse.

The most important members of your posse will be creators, pundits, and scenesters themselves. Which brings us to Cory Kennedy, the jailbait patron saint of L.A.’s dirty-fashion scene.

Team Cory started to form when the 16-year-old debutante became the intern/girlfriend of Cobrasnake, a party photographer and grungy hipster who makes American Apparel look like Disney.

Cobrasnake’s party blog grew in popularity every time a photo of Cory appeared. To feed the monster, Cory started her own blog. High-profile L.A. clubs began paying Cory $100 to show up with a retinue of friends, mostly culled from her MySpace Top 8. By this point she had become the hero of an entire subculture of “scenequeens” who kept her name alive by mimicking her style, chatting about her on LiveJournal and Buzznet, and creating an endless stream of video montages of her.

Microfame is an ecosystem, a collection of fans who contribute and invest themselves in the brand called you. The best current example of this esprit de corps in action is the diaspora of former Gawker editors who have picked up microblogging. Alex, Doree, Choire, Jess, Elizabeth, Emily, and Josh each have their own sites, but their cross-references and incestuous linking have created a blogger’s version of Entourage.

The posse—or as media theoreticians call it, the network—creates influence that grows exponentially with its size. If fame is an investment, the members of your posse are the stockbrokers keeping your wealth properly distributed.

Step No. 6: Diversify.

Very few celebrity entrepreneurs have mastered this new world of multichannel distribution—except for Tila Tequila.

With an album, a reality-TV show, and more fans than anyone else (besides Tom) on MySpace, it might seem that Tila Tequila has crossed over from microfame to full-fledged celebrity status. But Tila is actually the embodiment of microcelebrity, a changeling who mastered several niches rather than creating a single dominant audience.

Tila Tequila is a platter from which to choose. There’s Tila the sex kitten, who has appeared in Playboy and Stuff. But there’s also Tila the ninth-wave feminist, who has turned her official Web presence into a family-safe respite for teen fans. And there’s Tila the raunchy bisexual, a completely fabricated role she plays on A Shot at Love on MTV. Don’t forget Tila the pre-fame gangster girl, Tila the tweeny pop musician, and Tila the entrepreneur with a clothes line.

Tila Tequila is the anti-Madonna. Rather than building a super-persona that dominates all media platforms, Tila doles out a different identity for each platform. And though her protean antics hardly dominate any one arena (her debut album sold only 13,000 copies), Miss Tequila has spread her microfame empire by diversifying.

Step No. 7: Create controversy.

Andy Warhol once described himself as the type of person “who’d like to sit home and watch every party that I’m invited to on a monitor in my bedroom.” Just imagine what he would have done with today’s two-way television, the blog. It would probably look a little like Perez Hilton’s.

Hilton has built a small media empire—that now comprises a blog, a VH1 show, a record-label imprint, a musical, and a syndicated radio show—by becoming a synonym for controversy. Although it’s a crowded field, his most notorious stunt was probably declaring the death of Fidel Castro—very prematurely. He has been sued for incidents involving Britney Spears (song leaks), Samantha Ronson (false reporting), Colin Farrell (sex tape), Jennifer Aniston (topless photos), and the paparazzi agency X17 (stealing photos).

X17 may be the most interesting, because it is, like Perez, a parasite to celebrity culture. When pressed about his own fame, Perez has asserted that he’s not a real celebrity, instead positioning himself as a Hollywood outsider. It seems a necessary move, because to persist as the Prince of Microfame, he needs to subjugate himself before the truly famous.

There are myriad ways to stoke the coals of controversy. The personal dramas of the microfamous—like Emily Gould, the former Gawker editor best known for oversharing her romantic exploits and then writing about the oversharing experience for The New York Times Magazine—can be deployed in a similar manner to that of the truly famous.

Step No. 8: Persist.

If you’ve followed the road map, taken your time, and slowly climbed your way up the ladder, you should be at the point where, if you really want microfame, it’s yours for the taking.

Your next big problem will be staying relevant.

Remember Judson Laipply? Though the name probably looks unfamiliar, you are likely among the 86 million people who have seen him in “Evolution of Dance,” the most popular video of all time on YouTube.

Exactly. That guy.

While the page views on that video continue to tick upward, he has been unable to reproduce his past success. The Internet is flush with these one-hit wonders, a list that includes D.C. sex blogger Washingtonienne, treadmill rockers OK Go, faux-Japanese Webcammer Magibon, and even, so far, Ashley Dupré, who has been unable to turn her moment in the spotlight into any significant type of fame or financial gain.

While some people quickly fade from public consciousness, another kind of person seems to mysteriously—sometimes frustratingly—persist. Jakob Lodwick called these people fameballs, “individuals whose fame snowballs because journalists cover what they think other people want them to cover.” Lodwick himself is a good example. Though he probably wants to be known for his entrepreneurial efforts, like co-founding Vimeo and Normative, he’s probably best known as Julia Allison’s ex-boyfriend. And he also happens to have a photo spread in Esquire this month.

To persevere in the new age of celebrity, you need to return to the well, repeating these steps of creating, oversharing, and responding.

STEPS TO MICROFAME

• 1. Self-publish

• 2. Stylize

• 3. Overshare

• 4. Respond

• 5. Ally

• 6. Diversify

• 7. Create Controversy

• 8. Persist