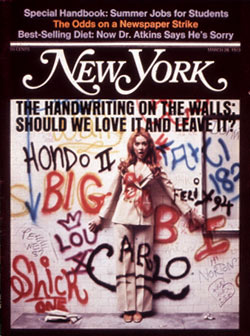

From the March 26, 1973 issue of New York Magazine.

Hard Times: New York’s Neediest Cases

At this season, every two or three years, it has become customary to appeal to New Yorkers in behalf of a group of citizens in our midst whose need for understanding and support becomes heart-rendingly acute.

This group consists entirely of our three surviving daily newspaper publishers and the thirteen labor unions they must deal with in order to stay in business.

The periodic failure, often in odd-numbered years, of newspaper publishers and their unions to agree on terms for new contracts is one of the few reliable ways New Yorkers can tell that spring has arrived.

This year, we appeal to New Yorkers to have a special care for these fellow citizens. Contracts between the newspaper publishers and most of the unions expire at midnight, March 30, and the odds on their ability to reach new agreements this time around are unusually difficult to calculate. Ultimately, all issues in their disputes come down to a matter of money, but this time some of these issues are masquerading as matters of principle. Should this confusion persist, participants on both sides of the table would be venturing on new, and therefore unpredictable, ground.

New Yorkers may be sure that their sympathy, whether applied or withheld, will not make the slightest difference. Previous strikes, to say nothing of the death of four dailies in the past ten years, have proven that New Yorkers can live without newspapers altogether.

In any case, the issues standing in the way of a new agreement will be resolved in total indifference to the needs and temper of the general public. Settlements are invariably reached only when each side becomes convinced, all over again, of the other’s willingness to commit economic mayhem—through a strike, a lockout, or other tactic—in order to make its position clear and credible.

But your gift of understanding to the needy cases described below will speak well of you as a person.

All of the stories on these pages are true. In some cases, the identity of a person uttering a useful observation has been withheld at the person’s insistence. This is because people involved in the publication of newspapers often believe that what they really think is nobody else’s business.

In all cases, the plight of these needy has been attested by audited statements, plus verifiable rumor or common gossip.

[Case 101]

A Scion’s Struggle

Arthur S. is now 47. Grandson of the founder-publisher of our modern New York Times and son of that great man’s worthy successor and son-in-law, Arthur S. was a late child, preceded by three sisters and a good deal of speculation, if not anxiety, about a male child’s ever coming.

In 1963, at the tender age of 37, Arthur S. acceded unexpectedly to the position of publisher of The Times. He was called on to demonstrate his fitness to command the best newspaper in the country before a notoriously skeptical audience consisting mainly of journalists and other publishers, some of whom confidently expected —perhaps even hoped—that he would fall on his face.

Psychologists agree that this is an unpleasant spot to be in.

For much of the ensuing decade, it had been Arthur S.’s cruel lot in labor negotiations to resist new wage demands while The Times’s profits were bordering on the obscene. In the past three years, however, The Times’s earnings have fallen precipitously—from $31 million in 1969 to $13 million (pre-tax) last year.

The decline coincides with a three-year labor contract Arthur S. had agreed to in March, 1970, an agreement that more closely resembled a suicide pact. Minor variations aside, the contract called for money increases in various forms (in retirement, health, or other benefits as well as wages) amounting to 15 per cent the first year, 11 per cent the second year, and another 11 per cent the third year—a 42.69 per cent boost, compounded, over the life of the contract. In return, The Times got absolutely nothing from the one union it most urgently needed something from—Local 6 of the International Typographical Union. The Times and Big Six could not agree on ways to permit the introduction of new equipment that would lower The Times’s production costs.

As the presumed boss of The Times, Arthur S. has taken much abuse for going along with the “15/11/11” formula and getting nothing in return (except, of course, three years of peace). He has been vilified by his peers in town and across the country. He has been relentlessly second-guessed by colleagues within the Times building on West 43rd Street. He has even been spoken of contemptuously by some of the very union leaders who engineered his consent. “He is soft,” they said privately.

Arthur S. has been humiliated on Wall Street, too. “You are soft,” security analysts have said to his face. On the American Stock Exchange, the common shares of The New York Times Company have recently traded near their all-time low. Investors now pay just $12 or so to command one dollar of Times Company profits—a price-earnings ratio more appropriate to second-rate steel companies than first-class publishing empires.

Arthur S. carries on bravely, nevertheless, and maintains a cheerful outlook. The elimination of at least 80 job slots within the Newspaper Guild’s jurisdiction in the past fourteen months was interpreted as “constructive” behavior by his peers, who take it as evidence of his essentially good character. He shaved one-eighth inch from the width of his newspaper. The difference is imperceptible to the reader and will be worth some $400,000 in paper saved this year. He has also acquired, at considerable expense, other businesses to lessen his dependence on newspaper profits.

As a result, the case of Arthur S. may no longer be one of terminal softness. But until the present negotiations are concluded, no one will know with certainty how “hard” he is—least of all, perhaps, Arthur S.

Case attested by the accounting firm of Haskins & Sells

[Case 102]

Tragic Victim

For the men who run The News, the last half-century has been a series of rude and undeserved surprises ending in tragic alienation.

Bad enough that despite the teachings of the newspaper’s own editorial writers, who have slaved ceaselessly to show the irrelevance of labor unions in an age of enlightened capitalism, the unions themselves ungratefully refuse to wither and die of their own accord.

Worse, fellow publishers in town have shown an unseemly disposition to make peace with their unions by sacrificing principle.

Worst of all, out of necessity so has The News.

Spawned by The Chicago Tribune in 1919, and still controlled by that newspaper, The News made handsome profits for many years despite the immature behavior of its unions, whose leaders, in their incessant nagging for more money, showed no self-discipline.

But the rich days are over. Stuck with the same 15/11/11 wage formula The Times bought, The News today is not the moneymaker it was. One student of the newspaper business describes it as “better than a marginal operation, but not much better.”

It has fallen to a 54-year-old executive named Winfield Henry (Tex) J. to lead The News in the present talks. Tex J. is caught between prudence and principle.

He has no choice but to negotiate with his craft unions through the Publishers’ Association of New York. The alternative, to bargain independently without the support of his fellow publishers in a united front, is out of the question. It would allow the unions to pick off the papers one by one, whipsawing them, playing each one off against the others.

But to preserve their united front, the members of the Publishers’ Association have had to adopt a rule of unanimity—all must agree on a bargaining position or there is no position.

In Tex J.’s view, those who know him say, the publishers have made disastrous compromises over the years to achieve unanimity. Throughout the past decade his fellow publishers were far readier than The News to scuttle principle in the name of expedience. These earlier deals, Tex J. fears, will prove to be embarrassing precedents standing in the way of desperately needed change—especially changes that must be wrung from the I.T.U.

In 1961, for example, the publishers agreed to reward Big Six for permitting the use of so-called “inside tape”—copy in the form of perforated paper ribbons produced within the newspaper’s own plant and fed into typesetting machines. The tape sets copy faster than men at Linotype keyboards can. The reward was modest—one day off with pay for the I.T.U. cardholders covered. And it was only The Times’s problem since only The Times was using inside tape in those days. But it was an opening wedge in what was later to become the can of worms known as the “automation issue.”

In 1965, the publishers rewarded I.T.U. for permitting the use of “outside tape” as well—stock market tables, specifically, supplied in punched tape form by the wire agencies. I.T.U.’s share was 100 per cent of the direct savings. (The publishers benefited by other savings made possible by the tape—faster closes at deadline, to name one.) Even the amount of tape a publisher may use is now subject to negotiation with the printers’ union. A special fund was set up to receive the payments called for. This provided a precedent for Big Six’s sharing directly in productivity gains (as distinct from indirectly, through wage clauses).

In 1965, too, a clause was written into the contract confirming the I.T.U.’s right to negotiate the terms under which new equipment might be introduced into composing rooms. In their hearts, publishers believe that this is a prerogative any self-respecting management must reserve for itself. In accepting this “bar” the publishers gave the printers a veto, which is still in effect.

The lavish 1970 settlement, which let the automation “bar” stand for another three years, was resisted to the last by The News. This is the year, Tex J. is said to feel, that the publishers’ chicken comes home to roost.

Tex J., then, is the tragic victim of an unresolvable conflict. His caseworkers worry that to remain within the Publishers’ Association is to remain in bad company. But without any friends in his peer group, they fear that he cannot build a secure future.

There is some hope that with aid and encouragement, and under the lash of economic necessity, his friends will pick up good habits from him, thus lessening the gap between them and ending Tex J.’s tragic alienation.

Case attested by the Audit Bureau of Circulation

[Case 103]

Careworn Mother

This is the unfinished story of Dolly S., who is 70.

Dolly S. has given 30 of the best years of her life to keeping The New York Post alive. It has been a thankless task. The Post is one of those unpleasant invalids who outlive the people who send get-well cards, but refuse to get well.

From the day she took over the paper in 1943, life for Dolly S. has been a ceaseless struggle against discouraging odds. Her problems are as large as those that afflict New York itself, from the flight to the suburbs of the white middle class to the congealing of traffic on the city streets.

There was a time when Dolly S. knew hope. Once, she competed against three other citywide afternoon dailies—The Sun, The World-Telegram and The Journal-American. Dolly S., born to wealth, lovingly spooned money in, and somehow The Post survived.

Life brightened for Dolly S. in 1967 when The World Journal Tribune died. The interment included the last traces of The Sun, The World-Telegram, The Journal-American, and the morning Herald Tribune to boot. The Post’s circulation, under 330,000 in 1966, soared beyond 700,000 in 1969. Dolly S. started making some money and gamely plowed it back into the newspaper. She moved into the old Journal-American plant on South Street, increased the page size so that it was a full column wider than standard tabloid, and sank some fresh money into multicolor presses.

Sadly, her happiness was to be short-lived. It turned out that for the purpose of getting out an afternoon paper in New York, the plant on South Street with The Post in it was as badly located as it was with the J-A there. The increase in page size did nothing for what was printed on it; The Post continued to offer aesthetic insult and the weakest journalism in town—terrible to look at and heavily dependent on wire service coverage, relieved only by some good cartoon strips, some columnists and the point spread on upcoming sports events.

Even the new color presses have yet to start paying their way. Indeed, they have yet to start rolling. Although they have been in for some three years, the manpower to run them has been the subject of prolonged negotiations between The Post and Local 2 of the New York Newspaper Printing Pressmen’s Union. Under the terms she has just accepted, according to one well-placed observer on another paper, Dolly S. “will be loaded up with all kinds of extra people. I’m sure none of them are needed. It’s an exorbitant settlement.”

Dolly S. has recently had to endure one especially painful consequence of the 1970 negotiations. Like The Times, The Post raised its newsstand price from 10 cents to 15 cents after the 15/11/11 package was wrapped up. The Post has lost some 95,000 readers since the increase. It’s down to 607,000. (The Times was hurt almost as much—down 85,000, to 815,000 daily. Circulation of The News, which went from 8 cents to 10 cents, has held up and lately gained a bit. It’s now 2.1 million daily, 3 million on Sunday.)

Careworn but undaunted, Dolly S. continues to nurse her ailing baby. She proved her grit beyond all question in the 114-day strike and lockout of 1962-63, the most traumatic of all episodes in the history of New York newspaper negotiations. Toward the end of that strike, the longest ever, Dolly S. resigned from the Publishers’ Association and, with the blessings of all the unions, resumed publication. She simply agreed to accept whatever terms the other publishers hammered out, and that was that. For three weeks thereafter, The Post looked like a regular big-town newspaper, at least on the ad pages, with classifieds and big retailer display stuff as never before, or since.

Dolly S. in time rejoined the Publishers’ Association, but her mettle in that crunch a decade ago is very much on the minds of the other publishers today. Some of them assume that should negotiations break down on March 30, Dolly S. will not shut down, because she simply cannot afford to.

One of the things observers are most hopeful about is Dolly S.’s will to live. As one member of the publishers’ negotiating team puts it, “Dolly S. is no gentleman.”

Case attested by the Audit Bureau of Circulation

The Uses of Candor and the Wages of Stupidity

The real-life situations of Arthur Sulzberger of The Times, Tex James of The News, and Dorothy Schiff of The Post are as grim as their case histories suggest. The newspaper business in New York has been bad news for some time now.

Whole categories of advertising that newspapers used to have a lock on— food merchants, clothiers, even book publishers—have been defecting increasingly to radio and television. The proliferation of branch stores of downtown retailers has been a bonanza to these competing media with their wider reach, and to suburban-based newspapers as well. Meanwhile, the number of spots in town where one can buy the three citywide dailies has been declining for a decade. The daily Times, for example, had 6,156 sales outlets in 1962. By 1973 the number had fallen to 3,581. And over the same period, of course, all newspaper costs have soared.

There is only one novelty in all this bad news. That is the possibility—still faint but at least visible—that this year the unions are beginning to believe it. In a recent monthly bulletin to his membership, President Carl Levy of the Newspaper and Mail Deliverers’ Union discussed the dim prospects now before the two morning papers’ bulldog editions—the editions that hit newsstands the night before—in astonishingly temperate tones. Said Levy:

… The circulation figure of The New York Times bulldog has reached an all-time low of approxiof men that are currently involved mately 12,000 papers. The amount in the delivery of these papers results in the cost factor far exceeding the return for The Times… . Complete elimination of The Times’s bulldog, as small as it may be, would result in some revised thinking of the bulldog situations at The Daily News [which is also at] an all-time low… . I do not want to sound like a spokesman for The News or The Times, but in all honesty we will be doing ourselves more harm than anybody else if we do not try as hard as possible to sell these papers and keep it alive… .

Levy hastened to add that he had not gone soft in the head. Indeed, he tactfully reminded his men that in 1970 he had foreseen the difficulties the bulldog editions were headed for and had been ready to strike in order to protect the union’s interests. But even in that part of the message there was a sense of balance and mutual need:

… It is true that in the last contract, due to the threat of a strike, we managed to obtain a clause which guaranteed no lay-off for the present men affected by the bulldog delivery if it will be phased out or eliminated. The clause would give us considerable consolation as far as steady jobs are concerned. [But] with the loss of the bulldog edition, it would create a tremendous loss in earning power for men that are making overtime because of the bulldog and it would eliminate a certain amount of extra work… .

The Deliverers’ Union has traditionally been tough at the bargaining table. It would bode well for the present negotiations if Carl Levy could bring that openmindedness into the same room with the publishers, and if the publishers could match it. That would leave only the electrical workers, machinists, mailers, paper handlers, photoengravers, pressmen, stereotypers, the Newspaper Guild, and the I.T.U. to go.

With so many different unions involved, too much should not be made of one temperate comment Carl Levy offered in January. But the fact remains that this year Levy is not alone. Jack Deegan, executive vice-president of the Guild, does not buy the idea that Punch Sulzberger is one of New York’s neediest cases—”not with the profit picture as we understand it,” he says. On the other hand, he remarked, “there may be some things that even we would agree they can’t afford. The Times has had even more staff reductions than The News or The Post.”

If the newspapers have indeed gained the union’s attention this year, it probably won’t be because the leadership now thinks the publishers may be right, but because just three publishers are left. As a direct result, membership of the Newspaper Pressmen’s Union has fallen from 2,800 in 1966 to 2,400 today. The Newspaper Guild’s membership is now 4,310, down from 5,700 in the same period.

Down, too, is the membership of Local 6 of the International Typographical Union, and that fact may be more helpful to the publishers than all the other facts and figures they will trot out to document the bind they are in. In 1966, when the Telly, the J-A, and the Trib were around, Big Six boasted 8,700 members. Today, it has 7,600.

The death of those papers cost the I.T.U. 850 jobs. The other 250 were lost because of a slow decline in the commercial printing business, New York’s second biggest industry. When the commercial printing business, New York’s second biggest industry. When the commercial printers were still bustling, Big Six could reasonably take the position that it was not the proper business of the union to subsidize inefficient, uncompetitive newspaper publishers. Now, with unemployment endemic among I.T.U. members, the old let-’em-die argument no longer sounds quite so reasonable.

Of all the unions involved, however, it is the I.T.U. alone that has more—much more—to offer the publishers this year than a mere willingness to show up for work if the price is right. The New York publishers desperately need to modernize their composing rooms. If, after a decade of unyielding resistance, Big Six were now to agree to bend the automation bar, if not eliminate it, the publishers would be terribly grateful, in cash.

In the wake of a big breakthrough, several complications would immediately arise. If the publishers were to settle a lot of money on the I.T.U. in return for permission to modernize, this might inspire other unions to raise hell on what might be called the “son-ofabitch principle.”

The other unions, this principle holds, have generally gone along with publishers’ efforts to update facilities and raise productivity. Meanwhile, the I.T.U. has been acting like an S.O.B., refusing to let them do anything. Now, if the I.T.U. suddenly says, “Okay, we will stop being an S.O.B. but you will have to pay us something extra for it,” how do the other union leaders justify not having been S.O.B.s?

“…’With all that hair-splitting going on, never underestimate the power of parochialism and stupidity to louse things up’…”

A partial answer may lie in recent precedent. The I.T.U. managed to win a direct share in the savings from outside tape without inciting the other unions to rebel. But the past may be an unreliable guide to the future. If the price for bending the automation bar is set high, it might prove an irresistible target for the others.

Another complication arises from the very scale of the new technology now available to the publishers. Consider the nice lady at The Miami Herald who takes your classified advertisement to sublet the condominium. She gets it all down at the keyboard of an I.B.M. Selectric. In a single transaction, this single employee will have furnished copy in tape form which, with an assist from a computer, will hit the Linotype with lines already justified. She also activates an automatic billing routine— as well as a check on your credit rating.

At The Miami Herald, a non-union shop, this is old-hat. Within six months, The Herald expects to go from hot-metal to photo-composition. In New York the Selectrics and automatic credit checks are only now beginning to fall in place. But the output of such systems will wander through at least two different jurisdictions. Ad taking and billing tasks fall within the Newspaper Guild’s jurisdiction. Setting the ad copy itself is the I.T.U.’s. The computer itself, presumably, is no problem, but whose hands are on the Selectric keyboard?

Here, alas, recent precedents aren’t very helpful, for no clear pattern has emerged. And this could be a very tough issue. “If you fool around with a union’s jurisdiction,” says Sam Kagel, a veteran West Coast mediator, “you’re fooling around with its soul.”

This year’s newspaper negotiations, then, would seem to come down to three, or at least two and a half, issues: a money package for everyone, a hassle of the first magnitude with the I.T.U. over the automation bar, and the possibility of jurisdictional disputes.

It was hard to tell underneath all the smoke starting to seep from the principals, but as negotiations began to get serious in March, both sides seemed optimistic about chances for heading off a strike. “I think we can get through this,” said Bill Kennedy of the Pressmen’s Union, “if no one miscalculates.”

That’s some “if.” With so many union and publisher subcommittees splitting hairs in hotel rooms all over midtown, says one veteran of these trials, “never underestimate the power of parochialism and stupidity to louse things up.”

Only a nut would claim to know whether there will or won’t be big trouble this year. The only thing sure is that the publishers will sound like tigers, the unions will snarl back (and perhaps disrupt normal operations for discrete periods of time just to remind everyone that they have teeth), and that this will probably go on right up to the deadline.

But events, at least, seemed to be strengthening the publishers’ hand. After the Nixon Administration scrapped Phase 2 wage guidelines, there was some fear that in the absence of a clear limit, and in the presence of continuing inflation, the rank-and-file’s expectations would soar, making it necessary for the union leaders to call a strike simply to prove they were in there trying. But it now seems at least as likely that the rank-and-file are more concerned with job security. (Among all the unions, only the I.T.U. has a strike fund built to last over long distances, and most of that is not in Big Six’s grip but rather in the hands of the international leadership in Colorado Springs. Relations between the local and headquarters are strained.)

Even rumor seemed to be strengthening the publishers’ case. There was the old rumor, now taken as fact, that oil millionaire John Shaheen is following through on plans to start a new afternoon paper. It would be almost entirely a non-union operation, and so technically sophisticated that Shaheen had plausible hopes of starting up with a staff of perhaps 100. The Post employs 1,200.

The unions had some rumors going for them, too. Newsday, it was said, was staffing up to bring copies from Long Island into midtown in large numbers in the event of a strike. (Publisher William Attwood flatly denied it.)

Another rumor had it that The Times and The News had determined to defy any picket line and try to break a strike’ should one occur. One union leader claimed to know that exempt— that is, non-union—personnel from both papers were already in Orlando, Florida, like ballplayers in spring training, boning up on certain mechanical tasks, and that exempt secretaries were taking seven-day crash courses in essential routines in East Orange, New Jersey.

But on balance, the feeling seemed to be that the economic case to be made by the three surviving publishers was strong, that the radically changed universe of the New York newspaper business made that case stronger still, and that for the first time in living memory the unions seemed disposed—if not compelled—to at least listen to it. Their income statement aside, the surviving publishers never had it so good.

Unquoted in this report—indeed, unmentioned—is the leader of Local Six of the I.T.U., Bertram Powers. This is because, as best I can judge, everything you have previously read about him, good or bad, is true. But in addition to being exceedingly able, exceedingly bright, exceedingly rigid, and exceedingly excessive, the betting here goes that he is not indefinitely immune to facts, and that this time Powers will have to give something in order to get.

The last time I was wrong was in 1946, when I misread a Long Island Rail Road timetable and missed a train to Rockaway Park.