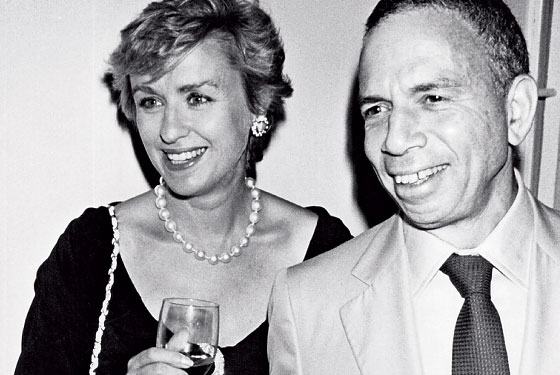

S.I. Newhouse Jr., chairman of Condé Nast, falls in love with his editors. His romance with Joanne Lipman began over lunch at his U.N. Plaza apartment, with its beige carpets—no red wine allowed—and paintings by Warhol, de Kooning, Cézanne. Lipman, 47 years old, who’d spent her entire career at The Wall Street Journal, is a serious journalist with a serious mien, and long legs, which she likes to show off with short-skirted power suits. Lipman is “attractive,” in Newhouse’s vernacular—“He uses the word like others use the word spiritual,” says a former editor. The two brainstormed at a small dining-room table. Newhouse, in his standard worn New Yorker sweatshirt, told her he had an idea for a business magazine. Newhouse didn’t say much more; he rarely does. He asks questions. But Lipman excitedly filled in the details.

Newhouse’s pursuit of Lipman was unusual. In most cases, someone else winnows future editors, presents the possibilities to Newhouse, shapes the conversations. But Newhouse, this time, made a point of doing it himself—Portfolio was very much his thing. And by the end of the day, he’d decided he wanted her to be editor of the magazine he planned to launch, which would be called Condé Nast Portfolio. Newhouse pledged patience and breathtaking resources—said to be more than $100 million over five years.

It was a great romance even if, like many great romances, others shook their heads about it, wondering whether Newhouse’s passion for Lipman was entirely rational. Business magazines were, after all, in decline. And soon, turmoil in Portfolio’s offices, along with incessant leaks to blogs and tabloids, made Lipman seem a caricature of the imperious Condé Nast editor, ruling from on high, out of touch. Even factions within the Newhouse family believed Si was blind to the real situation at Portfolio—“a good idea, badly executed,” was how one person described the magazine.

Finally, Newhouse himself couldn’t ignore the economic realities. Portfolio was on track to lose $15 million in a year; the total cost may have ballooned to as much as $150 million. On April 27, Newhouse summoned Lipman, this time to his eleventh-floor office, with its giant Andreas Gursky photograph of the NASDAQ sign on the outside of the Condé Nast building, to deliver the difficult news. In the past, Newhouse’s breakups had been unsentimental. The past was over—he moved on. His editors sometimes saw it on TV or heard it from others. This one was different. “I love Portfolio,” he told Lipman, with obvious feeling.

“I love it too,” Lipman replied.

A star-crossed romance. “It was painful,” says one person close to him. “It wasn’t just a financial investment. He had great hopes for it.”

Newhouse has never been one to show much emotion. But in the last two years, he has had to close Jane, House & Garden, Men’s Vogue, Golf for Women, Domino, and finally Portfolio. At Condé Nast, the rumor mill, accurate or not, continues to grind. Which will be next? Wired? Architectural Digest? Does the company really need two food magazines? The grim work has taken a toll. His own personal wealth has declined by half, to some $2 billion, but personal wealth was never the point. “Without Condé Nast, he would cease to exist,” says a person close to him. “It’s where he comes alive.”

So when it dies a bit, he does, too. “I’ve never seen him so depressed,” says one person on the publishing side. On his next birthday, he’ll be 82, and Portfolio may have been his last great fling. Who knows whether he’ll get to launch another magazine?

Si Newhouse is nothing like his magazines. Short, physically unimposing, dressed for the office in khakis and beat-up loafers, he’s the opposite of glamorous. “He’s always had the luxury of being himself,” says a friend. He’s notably inarticulate, speaking softly, with long, excruciating pauses between words. A decision to commit millions of dollars might be communicated with a “very, very quiet whispered yes,” says one of his former editors.

It’s a type of decision Newhouse, one of the great media entrepreneurs of the past three decades, has made with breathtaking regularity. In 1979, when magazines like McCall’s, Good Housekeeping, Redbook, and other sensible books were leading women’s titles, Newhouse started Self magazine for a new generation of restless, body-proud female readers and bought GQ for a new style-empowered man. Four years later, he relaunched Vanity Fair, which—after years of huge losses amid editorial floundering—channeled and helped create the arriviste dreamscape that took off in the eighties. Along the way, he purchased The New Yorker, then brashly rebuilt it, grafting its sedate Shawnian DNA to Tina Brown’s topical buzz, creating a fascinating Frankenstein that still is at the core of the magazine’s identity. He also remade Details, a trend-dipping downtown title, and bought Wired, the champion of the technological revolutions that now nip at his empire.

Though Newhouse built Condé Nast with ruthless commercial motives—when someone asked him about the purpose of his company, his answer was, simply, “To make money”—there are clearly other motives at work. “He loves magazines, meaning the whole and all of it, the variety of things published, the business details, the visions and actions and personalities of his editors, the problems, the problem-solving, the ink and paper … the all of it,” David Remnick said to me.

If Remnick’s remark sounds a bit like a eulogy, it’s because it very well might be. Condé Nast, like all magazine companies, is struggling. The luxury market on which Condé Nast depends is anemic, with no cure in sight. And the Internet, workaday and diffuse and all-too-democratic to an elitist like Newhouse, competes for the dollars that remain. Almost all of his magazines have been hammered by the downturn (as have most magazines, including this one). Wired ’s ad pages are down almost 60 percent in the first three months of this year versus last; The New Yorker’s are down 36, Vogue and Vanity Fair both around 30 percent. Newhouse has long been a modernist, with forward-looking instincts, his timing not too far ahead and never behind, but suddenly he seems to have become a kind of magazine sentimentalist, in love with a world that more and more exists in the past.

One of the stories Si Newhouse tells about his father, Samuel I. Newhouse, known as Sam, is how he came to purchase the Condé Nast company. Just before his 35th wedding anniversary, Sam, a tiny bulldog of a man, departed for work before dawn, as always, and returned later that day with a present for his wife: Vogue magazine, the jewel of Condé Nast’s five titles. “My father bought the company as a gift for my mother,” Newhouse likes to say. It’s told as an affectionate story about a distant, work-obsessed father—“My complaint about time spent on the job is that there is not enough of it,” Sam once wrote—and the even tinier wife he doted on. But it’s also revealing about father and son.

Sam was a newspaperman—Si didn’t see much of him until he was old enough to visit the Staten Island Advance, Sam’s first paper. By Sam’s death, at age 84, he’d amassed a newspaper empire that stretched from Newark, New Jersey, up to Portland, Oregon, larger, by some measures, than that of William Randolph Hearst’s.

Both of Sam’s sons were college dropouts who worked in the business from the age of 21. Sam tapped Donald, his younger son, to run the newspapers. Si was installed at Condé Nast—he finally became chairman in 1975. “Those who knew him well seem to think he trusted the judgment of his younger son, Donald, more than Si,” writes Thomas Maier in his excellent biography Newhouse.

It was clear what Newhouse’s father thought of magazines; they were baubles, suitable for socially ambitious middle-aged ladies. Si, though, would ultimately prove his father wrong about the value of the magazines and about his talents.

Newhouse’s magazine mentor was Alexander Liberman, who’d shined as art director at Vogue in the forties and became editorial director in 1962. A Russian-born, European-raised artist—he had minor renown as a sculptor and painter—Liberman had a gift for wooing the powerful. According to his stepdaughter, ambition was his animalistic outlet. He loved the court politics that developed at Condé Nast, and his Machiavellian tactics were both a way of doing business and a kind of aesthetic value, part of the company’s frisson.

Liberman and Newhouse eventually became an inseparable king and privy counselor, constantly conferring sotto voce. Liberman introduced the awkward heir to art and to artists and instructed him on the nuances of social calibration, like “who was famous and who was important,” different categories entirely, as a former publisher explains.

Liberman was also an original voice who talked in mystical terms about magazine-making, and his sensibility became the sensibility of the whole company. “He was a genius,” says Anna Wintour, editor of Vogue. Liberman prized magazines’ power to transcend the quotidian—“Dear friend, where’s the glamour?” he once woefully asked Harry Evans, the first editor of Condé Nast Traveler.

The two came to share a philosophy, which was, at its simplest, “Magazines are precious things,” as Liberman sometimes told editors. They require pampering and purity and, not incidentally, money. Liberman tore up layouts at the last minute and counseled editors to spend, spend, spend, because spending, too, was part of the aesthetic, almost an end in itself.

Newhouse’s father died in 1979, a year that coincided with a burst of creative and commercial energy that would reshape the magazine landscape. After Self took off, Newhouse relaunched Vanity Fair, a Condé Nast flagship that had failed during the Great Depression, with a bold but vague idea of a popularized, glossier version of The New Yorker. The magazine consumed huge amounts of cash, $75 million in its first few years. With its somber black-and-white covers by Irving Penn (a Liberman discovery) and sometimes effete content, it struggled to find a voice. Within a year, Newhouse had dismissed two editors before hiring Tina Brown, the first of his crushes and the first of Condé Nast’s famous editors. Brown “kick-started” the current incarnation of Condé Nast, says James Truman, Condé Nast’s former editorial director.

Brown concurs. “I brought in the news gene,” she says. “Newhouse came to understand that news was a key to connection to the culture.” But of course, what news mostly meant was buzz. Brown had an instinct, and an unrestrained affection, for power, and she set about glamorizing it, whether in politics, Hollywood, business, or crime. The notion that a magazine could borrow celebrity power to increase its own, such a truism now, was revelatory at the time.

Newhouse’s timing was exceptional. The thrusters under the boom economy were charging, and with them, a new type of reader appeared. Newhouse’s magazines appealed to what would be called aspirational readers.

As Newhouse rebuilt Condé Nast, his organizational inclinations became clear. He ran it as if it were a movie studio of the thirties and forties, the era in which Newhouse, a shy child, fell in love with the glamour of Hollywood. “One editor is like Hal Wallis,” Graydon Carter, editor of Vanity Fair, tells me, “another like Busby Berkeley, and there’s a commissary,” the Frank Gehry–designed cafeteria at the Condé Nast Building at 4 Times Square. For Newhouse, it was a wonderful setup. “He created [in Condé Nast] a reality in which he is no longer the bumbling, asocial kid he grew up as,” says one person close to him. In this analogy, Newhouse is in the role of Louis B. Mayer, the notoriously tyrannical MGM head who loved his stars but made them quake. “Si loves being surrounded by divas and egomaniacs,” says one former editor. When one editor called another a “fucking bitch,” Newhouse didn’t mind. “Yes, but she’s our bitch,” he said. He delights in the Darwinian drama that takes place below him. “He believes the best will rise and will not be shivved in the back,” says the former editor.

For Newhouse, studio life offers a further reward. Because of his own psychology, Newhouse can’t really express himself, so he’s created an environment in which all his nerve endings have projections in the world, in people, in departments. “All the major figures in Si’s professional life, the people who interest him, represent some aspect of him,” says a person close to him. “So while Anna or Graydon or David live off him, it’s also true that to some degree he lives vicariously through them. They’re all adjuncts or outbursts of Si, all acting out parts of Si.”

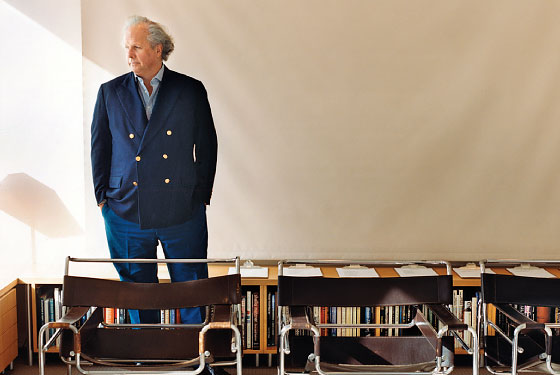

One afternoon, I ask Carter if he is worried about the future of magazines. We are in his office on the 22nd floor of the Condé Nast building. Carter has lately put on a few pounds, and his curved desk of blond wood seems cinched around him like a seat belt. “You try opening a restaurant and not gaining weight,” he says—weeks before, he’d opened the Monkey Bar, and before that the Waverly Inn, and one of his two assistants, visible through a connected sliding-glass window, takes reservations.

“If you’re competing as a daily or a newsweekly, you may have problems with the Internet,” says Carter. “For the monthly magazines, the clouds part a little and the sun comes out. If you tell stories and have great pictures, there’s a great future for you. I do think this company is pretty well suited for the future.” Carter’s view is the official view at Condé Nast, where the future is supposed to look a lot like the past. From the outside, however, Condé Nast can appear to be running scared. The impression flows not merely from the string of magazine closings, or the 5 percent payroll cuts, or the halt in pension contributions (part of what I’m told is a shrewd 20 percent reduction of expenses). In fact, it’s the petty trimming that seems telling, all those small profligacies—multiple receptionists, unlimited travel. Car service was practically part of the Condé Nast brand.

But when I suggest that all the closings might look like panic, Carter rises to the company’s defense. “Si doesn’t do panic,” he says, with exasperation. He insists that Newhouse has seen cycles come and go, heard the end of the publishing world foretold more than once. “It’s still a golden age of magazines,” he insists.

I arrive fifteen minutes early to Anna Wintour’s office, but an assistant still meets me in the downstairs lobby. “That’s what we do,” she says, a lovely swirl of blonde hair on her head and two cell phones in her hands. On four-inch heels, she leads me to Wintour’s communication director, who walks me down a long hall—a runway—to Wintour’s office, which is filled with vases of pastel-colored roses. The attentiveness is flattering, though I’m aware, having worked for Wintour a decade ago, that it’s part of her system of control. I mention to Wintour the forthcoming documentary about her, The September Issue, by R. J. Cutler, which follows the production of the largest issue in Vogue history, the September 2007 one—840 pages, 727 of which were ads. I’ve heard that Wintour didn’t feel the movie had enough glamour and tried to change it, without success. “It’s R. J.’s movie,” she tells me tersely.

Wintour’s portrayal of herself is flawless: the rail-thin arms, the now-blondish bob, and the all-business bearing—she still looks remarkably like Louise Brooks, whose image has hung in Newhouse’s apartment. Wintour tells me that at Vogue, conversations have evolved with the times—for instance, she now looks at the price tags of clothes before putting them in the magazine. “How many handbags, how many shoes, does a woman need?” she asks. It’s a nod to the times, not insincere but not hugely significant either. Vogue can’t not be Vogue; that’s crazy. “We stand for a certain world,” she says. “Women want to have pretty clothes. I mean, it’s a question of self-respect too.” Vogue is at heart an unchangeable and, in that, an optimistic venture. Wintour tells me about Ralph Lauren’s new collection of watches, which inspires her. They cost more, but they will last. “He wants to be part of the culture, and I feel the same way about Vogue: I want Vogue to be there, part of the culture,” she says.

If Newhouse’s stars are projections of his inward personality, then Wintour represents the glamour that he first fell in love with through the movies as well as his sharp controlling hand. And Carter is gregarious, voluble Newhouse, the boon companion in a fascinating town, Newhouse’s entrée to a Hollywood he still adores. Carter’s conversation is sprinkled with recollections of convivial dinners with old movie stars, Michael York or Warren Beatty, Bob Evans, and the Vanity Fair Oscar party. Carter delights in his own stories, reels me in with a naughty off-color intimacy. He talks about famous “stickmen.” At 59, he has an infant (Carter’s a stickman himself). And he still smokes. “I quit. I go back,” he says.

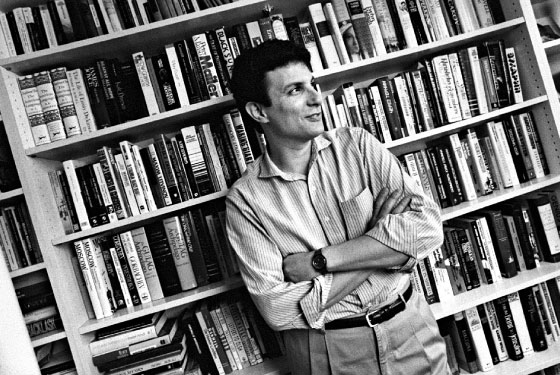

I meet David Remnick, 50, at The New Yorker conference “The Next 100 Days,” an important event at New York University. Remnick is wrapping up an onstage interview with Seymour Hersh, his investigative reporter, who is talking about as-yet-unrevealed machinations in Pakistan. “Okay, don’t say any more,” Remnick says, as Hersh starts to ramble. Remnick is Newhouse’s inner egghead, influential, earnest, and ostentatiously articulate, with an accent that flows freely from Princeton plummy to Yiddish—“Is everybody hokking you?” he asks me at one point—and back again.

“We stand for a certain world,” says Anna Wintour.

As we walk to a nearby diner in the West Village, Remnick checks in with his wife, greeting her in Russian—he won a Pulitzer for his book on the fall of the Soviet empire. Remnick is charming but wary, a working journalist who prefers the role of interviewer to interviewed. He reviews for me the differences between off-the-record and background conversations, and then we order salads. (“That’s pretty gay,” says Carter, patently not a salad eater, when I mention my meeting with Remnick.) Remnick salts his conversation with references, and they are all over the place, proudly high and low—J. D. Salinger, Mel Stottlemyre, Perry White, Heraclitus. Much like in his magazine, there’s showy, apparently effortless cultural fluency, though part of the message seems to be: Can you keep up?

Remnick’s view of the future of magazines is shaded darker than either of his colleagues’. The New Yorker’s profitability has slipped into the mists of Condé Nast’s notoriously murky corporate accounting. “Look, the economic climate is awful. There’s no reason anything in this world stays the same. Only a fool, and I don’t think there are any fools involved in this story, would assume that the picture, right at this moment, is going to stay the same.”

Each of Newhouse’s star editors feels intimately connected with a man not given to intimacies, though fascinatingly, each sees him in significantly different ways. Newhouse, says one former editor, is “semi-blank.” In a sense, he’s like a polished surface, and the editors tend to see themselves in him. To hear Carter tell it, Newhouse is a fellow bon vivant. “We’ve double-dated,” he tells me. And he notes that Newhouse can hold his liquor—“One thing you should know about Si: He’s incapable of getting drunk.” And by the by, he knows an outstanding steak recipe from old Chasen’s, now available off the menu at the Waverly Inn. Wintour warns me, “Si is in control, and if you write anything different, you would be 100 percent wrong,” control being a quality she admires. For Remnick, Newhouse is wide-ranging and intellectually curious; he too is a student of Russian history. During the elections, Remnick and Newhouse talked endlessly about Obama and politics, though Remnick never learned if Newhouse is a Republican or a Democrat.

What they do agree on is that none has ever had a better patron. Newhouse isn’t just a boss; he’s the person who stands between them and a crueler, more pragmatic world. Newhouse believes in talent and the mysteries of creativity. He doesn’t meddle. And they revere him for it. “The magazine is yours, Si has always let me know,” Remnick says.

“There’s no place on Earth like this,” Carter tells me. “There’s no place where you’re given the resources you need to do what you want to do and also given complete freedom to do it.” A short time ago, Carter says, he offered Newhouse some possible economies. “I tried to bring up money with him,” he explains. “I had some ways of cutting expenses around photo shoots. He just didn’t want to hear it. He got all uncomfortable. Si said, ‘Just make sure there’s nothing that can hurt the magazine.’ In my lunches with Si, you wouldn’t know that there’s anything different from 2002, 1996, 1992.”

Newhouse’s publishers represent an altogether different part of his personality—a darker, hungrier, more aggressive side. Newhouse sometimes refers to his publishers as killers. For years, Steve Florio, brash, crass, and, he said, blue collar, was the lead killer, “the Godfather, the Samurai, the leader, the warrior,” as he wrote in a book proposal. He was also a liar. In 1998, a Fortune article documented a roster of casual biographical embellishments, which taken together made him unemployable elsewhere. Newhouse defended him: “He tells just enough of the truth.” Many at Condé Nast were appalled by Florio’s “brilliant ridiculousness,” as one put it. But Newhouse has a kind of Spidey sense. “He so embodies the business and he’s so involved in it, it’s like an organism that is part of him,” says James Truman. “As a result, he has had a precognitive notion of what’s going to unfold and what the company needs.”

In 1994, after Florio’s disastrous run as publisher of The New Yorker, Newhouse promoted him to CEO, a shocking choice that proved visionary. At the time, Florio made a bold prediction to a meeting of Condé Nast’s publishers. “This company has always been about the editors,” he told the group. “Now you’re all going to be superstars.” And he was right. Florio’s publishers became stars with as much claim to “Page Six” as the editors. Ron Galotti, who was publisher of several Condé Nast magazines, dated models and later Candace Bushnell, who turned him into Mr. Big in Sex and the City. Richard Beckman, a former British footballer and a Florio protégé, became, if not famous, notorious. One tipsy evening in 1999, Beckman, then publisher of Vogue, smashed the heads of two young female Vogue staffers together, suggesting he wanted them to kiss. One of the girls, says a friend “looked like she’d been in a car wreck.”

At another company, the incident would surely have ended Beckman’s career. Newhouse, though, loved the kingdom’s rambunctious egos, especially if they produced, and Mad Dog, as Beckman was known, performed well. Newhouse stood behind him, paying a reported seven-figure settlement to the girl, and eventually promoted Beckman to head of corporate sales.

Newhouse could afford the settlement. Condé Nast rode the boom like few other magazine companies, and its business side sparkled. “For the next ten years, the company was about sell, sell, sell,” says one insider. Florio pushed Condé Nast into the top rank in number of ad pages sold, while constantly bringing home stories of shoving rates down clients’ throats. Newhouse knew the stories weren’t entirely true but loved them anyway. For years, Newhouse raised ad rates about 5 percent annually whether or not a magazine’s circulation increased. Last summer, the company raised rates by another 5 percent. “We’re a company that wants to be admired, not liked,” explains one publisher.

As harsh a manager as Newhouse could be, the upside for publishers was much greater. “You were selling ads for some shit-ass magazine, and now you’re the richest person in your community,” explains one former publisher. “If Si likes you, you will have a life you never imagined you could have.” Newhouse turned a publisher into an expense-account millionaire, flying first class and staying in the best hotels. The company provides key employees no-interest or low-interest mortgages. Publishers can receive a clothing allowance; two club memberships, one in town and one out of town; and a $1,500-a-month leased car. It wasn’t entirely wasteful. Newhouse wanted clients to understand that the Condé Nast brand was as elite as theirs.

In his own life, Newhouse doesn’t need perks. He’s appeared on the Forbes list of wealthiest Americans for 28 years, since its inception. In the Newhouse family, wealth doesn’t translate into worthiness. To Si’s father, one proved oneself through work.

Several years ago, Florio had walked into his office around five in the morning, the time Newhouse usually arrived.

“I know why I do what I do,” he told Newhouse, referring to the long days. “I have two kids to put through college.”

“Why do you do what you do?” pursued Florio.

“Ghosts,” he said. “You wouldn’t understand.”

When in 2003 Florio faltered after heart trouble, Newhouse called him at home, where he was convalescing over the holidays. Sales were off, and Florio wasn’t on top of the operation.

“You think it was a surprise to Steve Florio that he was fired?” says Galotti, whom Newhouse fired twice. “Absolutely not … Anybody who works for him knows that when his day is up, Newhouse will just do it. You know that one day, your ass is going to get it just like anybody else’s.”

Newhouse could fire with brutal swiftness and seeming indifference. “Si doesn’t do reverie or procrastination. He’s not romantic. He’s pragmatic,” says one person close to him. Publishers in particular are utilitarian, interchangeable as cards in a deck. “Si’s not cruel,” says a former executive. “It’s as if, after he’s made up his mind, he moves on. In Si’s mind, the person is already gone. Firing is an afterthought.” Following his demotion, Florio got a new title and office, but was no longer a player. He died in 2007 of heart problems.

Most executives get sent off with a fat check, which eases the pain. Still, many of the exiled are at a loss, having missed a central fact of Condé Nast: The lifestyle is on loan. “A kept luxury lady” is what Tina Brown told me she felt like.

The irony of this moment in publishing history, when the future seems so uncertain, is that Newhouse’s company has always looked years ahead, to the next big thing. Historically, Condé Nast’s profits have not often exceeded 5 percent of revenue, the reason being that the company was constantly sinking money into new magazines. The domestic magazines have under $2 billion in revenue. “The company could have earned another $50 million in profit a year,” says one source familiar with the financials. “But Si’s belief was the company constantly needed to be growing.”

Newhouse greenlit a magazine a year for the last dozen years, including Lucky in 2000 and Domino, another $100 million project, in 2005. Portfolio was a more ambitious project, a Vanity Fair for business and an essential market expansion for a company dependent on fashion advertisers. “It was a great idea for a magazine,” says Carter, before pointing out that Condé Nast already has a Vanity Fair for business … Vanity Fair. The magazine was an enormous gut-level bet, made with a kind of CEO’s heroic boldness, and from the day it was announced, it had a certain sprawling, uncontrollable Heaven’s Gate quality.

“It’s still a golden age of magazines,” says Graydon Carter.

Even as some questioned the reasonableness of Newhouse’s passion for Portfolio, in other ways the company was growing more orderly, less spendthrift, more like other companies. In 2004, he replaced Florio with Chuck Townsend, making him CEO and president. Townsend, 65, is the un-Florio, a toned, workout guy and past commodore of the New York Yacht Club—his office is decorated with photos of sailboats. “He looks like a CEO,” says Carter, who’d tired of the killers. “He’s clubbable.” Townsend is an operations guy, not an instinctive boat rocker, which is the knock on him. One former executive who worked closely with him says, “Most people care about making an impact. I’ve never seen Chuck push if a Newhouse doesn’t want to do something.” He went to work on the org chart, streamlining an unwieldy corporate structure. “Every year since I joined, the company got more and more fiscally responsible and focused,” says one former executive.

Now, instead of Mad Dog, publishers like the unflappably personable David Carey represent the culture. Carey, a suburbanite and enthusiastic corporate citizen, presided over The New Yorker as it climbed into the black in 2002, and he is widely praised as “a strategic thinker”—a pointed, if implied, critique of the Florio cult of personality. Newhouse tapped him for the company’s most prominent task, to publish Portfolio. “I like jobs that are hard and complex,” says Carey, who rarely speaks an out-of-line word.

Truman was another mid-decade departure. He’d relaunched Details (where I worked for him) in 1990 and became, at 35, the second editorial director in Condé Nast’s history. With impeccable taste and quirky pop-cultural enthusiasms, all packaged in “profoundly expensive” suits, as he once quipped, he was a slightly foppish Si-whisperer in the Liberman tradition.

Over ten years, Truman seemed to grow restless, even with his successes—Lucky, which was his idea, was more catalogue than magazine. “I told Si a couple of times about how bored I was with managing, and he said, ‘That’s the price you pay for being at the top of the company. I struggle with that, too.’ ”

Truman was determined that Condé Nast launch an art magazine, and the two men tussled over the idea for months, though clearly more personal issues were at stake. “Look, you should trust me. I know what’s going on,” he told Newhouse. “That’s why you hired me. You should let me do it.” Finally, there’d been a shouting match in Newhouse’s office, an unusual blowup that surprised them both with its intensity. An art magazine had no advertising base, Newhouse pointed out. “He was right,” says Truman.

Tom Wallace, Truman’s replacement, didn’t envision his role as a guiding creative force; that era was over. He worried about the web. “He’s the protector of high-level quality,” I’m told vaguely, though few editors seem to count on him, except for occasional help in interpreting one of Newhouse’s inscrutable shrugs. “Tom is not electricity. He is steady rhythm seeking perfection,” says Harry Evans, Wallace’s former boss. To some, the new régime seems a collection of organization men, fin de l’empire types marking the decline of an enterprise once bristling with unbound and misbehaving creative energy. One former editor says, “Si has surrounded himself with people who look and sound like executives.”

As the economy has fallen apart over the past eighteen months, first gradually then all at once, Condé Nast’s biggest problem has been the newspaper empire that Sam created. Last year, the Newhouses’ Newark Star-Ledger, one of their biggest papers, may have lost as much as $40 million. No one in the family believes the newspaper business is coming back. The family’s cable business, Bright House Networks, with enterprises in several states, still tosses off tens if not hundreds of millions of dollars, keeping the Advance, which houses all of the family’s businesses, afloat, and the company is virtually debt-free; the family has always hated to borrow. But resources are now spread thinner. The company no longer has the luxury of pumping cash into a struggling title. “The family needed to save money,” Townsend explained to one executive after one magazine closed. Without profit, there’s no “distributable cash” for the family. So far this year, Condé Nast is in the red, though the closings and cuts should drive money to the bottom line. The belief around the building is that next year, if the economy recovers, Condé Nast will again turn profitable.

While the strategy by which Condé Nast will move into the future does not entirely ignore the Internet, it does not exactly embrace it either. When a subordinate worries in a meeting whether the Internet will limit the amount of profit magazines throw off, Townsend may take the person aside, according to one former executive. “Don’t be so negative,” he’ll say. “You’re upsetting the old man.

Magazines in general and Condé Nast in particular are certainly not as threatened in the short term as are newspapers. But Newhouse has been slow to get his mind around any significant brand extensions into the new medium. For nearly a decade, Newhouse opposed purchasing Wired.com. Three years ago, Donald Newhouse’s son Steve finally pulled off the deal, and the website now has sixteen times more unique visitors than the magazine has in circulation. Still other towering brands like Vogue have lain largely fallow.

As a rule, Newhouse has kept his editors away from the web. He has also rarely pushed publishers in that direction, seeing the Internet as a vehicle for selling magazine subscriptions and not much else. And the revenues are comparably minor. He can’t get excited about them—“a painting to Si,” says one cynical former executive. Only about 3 percent of Condé Nast ad revenues came from digital last year, according to Advertising Age, among the lowest in its class.

Steve Newhouse, 52, Si’s nephew, is responsible for many of the companywide web initiatives, and though he hasn’t found a partner in his uncle, some of his ventures have been prescient. He helped create Epicurious.com and Style.com, both conceived as new brands for a world that would no longer be magazine-centric. The point has been less to make a profit than to position the company for a future in which Si Newhouse is gone and the Internet is central. “Maybe an 80-year-old man isn’t the best person to figure out what the next generation of readers wants,” says one former editor.

To a surprising degree, there’s a clannish, insular, old-fashioned quality to Condé Nast and its sister businesses. Newhouse and his brother, Donald, convene regular family meetings—a kind of tribal council—just as their father did. As befits their small-town roots, they distrust the outside world. They still have never hired an outside executive to manage the vast businesses. Says one person close to the family, “Business integration is a family affair.” The meetings are attended by perhaps twenty family members. There are reports from various business heads, like Bob Miron, 71, a folksy-seeming cousin who runs the profitable cable operation from Syracuse with his son and a daughter. The family works hard for unity; at meetings, family members voice opinions but respectfully. Nothing is voted on. “At the end of day, Si and Donald lead the decisions,” says an executive who’s attended meetings. By all accounts, the brothers are incredibly close. “If you’ve talked to one, you’ve talked to the other,” says a person who talks to both.

Ostensibly, everyone respects the process of governance. But there are clear generational differences. The younger generation is not so young—its members are in their fifties. “Are 50-year-olds pulling on the bits? How could they not be? Here’s Si, 81 years old, sitting in the middle of business,” says an adviser. Some of the frustration surfaced over Florio, whom the younger generation viewed as an embarrassment, Si’s folly, a sign of the old man’s misplaced loyalty or stupidity.

Si Newhouse is still the plenipotentiary, plunging into the details. But his age has been something of an issue. He can be forgetful. Sometimes the famous early riser dozes off in afternoon meetings, and he is slowly going deaf. No one doubts, however, that he’s firmly in control. “Newhouse is involved with whatever he wants to be,” I’m told.

No one expects him to retire anytime soon. Still, preparations are quietly being made for a time when Newhouse is no longer on the scene. The succession seems to have been largely settled, even if details need to be worked out. The kingdom will be gerrymandered among the sons and cousins along the lines of Townsend’s org chart. Bloodlines matter. Primogeniture is the rule. In business decisions, Steven and Michael, Donald’s sons, and Sam, Si’s son, “are first among equals,” as one person who’s dealt with the family on financial matters says. Bob Miron and his children will run the cable business. Jonathan, 57, the worldly London-based cousin with a British passport and a pocket square, will no doubt head the magazines. Jonathan already runs the international magazines, which number about a 100 and produce as much in revenue as the domestic magazines. More than the others Jonathan has shaken free of the family. “Brilliant to stake his turf, to get out of the middle of this family,” says a person who knows him. Jonathan enjoys his stature as an international media mogul. About Si, Jonathan told the Times, “I value his experience and wisdom. Still, we have our own business realities here.”

“Only a fool, and I don’t think there are any fools involved in this story, would assume that the picture is going to stay the same,” says David Remnick.

Steven is the other prominent next-generation Newhouse. He’s short, antsy, and more closely resembles Si, his uncle, with the family’s overwide smile. He lives in the West Village and is married to Gina Sanders, the publisher of Lucky. Steven’s role is more circumscribed than Jonathan’s, since he operates within Si’s realm and, at times, at his pleasure. Other executives say he can bridle at these limits. Steven, as if to compensate, has become a kind of protégé to Townsend, who, it’s pointed out, doesn’t resist the Internet. Steve will certainly be in charge of the company’s Internet efforts going forward.

The next generation waits patiently, but there is a clear sense of relief that Si’s domain is increasingly well defined—the emperor has become a division chief. The editors report to Si; the publishers report to Townsend, a significant shift. The days when one all-powerful person is in control are over. “Chuck Townsend runs the company,” says one executive, a fact that clearly pleases the next generation. There also is a tendency, however slight, to patronize the old man. “We’ve talked about this,” Townsend has been heard saying to Newhouse. “He doesn’t get in the way,” is a phrase people have used to praise him.

Some of the once-ironclad faith in Newhouse’s judgment has been eroded by Portfolio. The family was enthusiastic about the idea, but Si’s persistence in the original course was confounding. For the family, it was a delicate matter. “They didn’t want to usurp his prerogative,” says an insider. But ultimately they didn’t leave him much choice.

At this year’s American Society of Magazine Editor awards at Lincoln Center, the Pulitzers of magazine journalism, waiters in formal dress served canapés. And then the magazine Establishment filed into the auditorium, where Jimmy Fallon presented the first award, momentarily giving the event an Oscars-like feel.

Newhouse shuttered Portfolio the week before, but his surviving magazines dominated the awards, winning seven. Newhouse sat next to David Remnick, as he does every year, and cheered and cheered, more animated than anyone has ever described him to me. At one point, he jumped from his seat to clap award-winner Chris Anderson, of Wired, on the back. From the stage, editors issued warm shout-outs to Newhouse, who, though sitting in the audience, was the evening’s dominant figure. Remnick, who collected three awards, praised him as the Babe Ruth of magazines, swinging for the fences.

Later in the program, there was a special lifetime-achievement award for Annie Leibovitz, the photographer whose 25-year career at Condé Nast Newhouse has lavishly financed. Years ago, she signed a lifetime contract that pays her more than tens of millions of dollars, according to one insider.

Three of Newhouse’s editors, past and present, took the stage to praise Leibovitz, the diva of divas, the kind of exotic, cantankerous talent that could only exist in Si’s world. Annie shows up at photo shoots with two vans of assistants and equipment, commandeering the scene. During her baroque financial troubles, Newhouse rushed to her aid, making a personal loan said to be seven figures.

Onstage, Tina Brown, Anna Wintour, and Graydon Carter lined up, three of the four editors who praise Annie—Jann Wenner is the fourth. The stage was bare, like in a Beckett play, commanding presences waiting awkwardly on spots visibly marked in blue tape—the Oscarish aspirations broke down long ago.

Brown was in a modest dark dress, the assertive and unapologetic popularizer, rhyming jolt with volt to give a feel for the impact of Annie’s photos, and then, not quite done, comparing Annie’s photos to crack cocaine. Wintour in knee-high fur-fringed boots, hunched a bit forward at the shoulder. Almost shyly, she read from a prepared speech and talked about the glamour and the difficulties of working with Annie. Carter, in his blazer and his trailing white hair—like George Washington’s wig—asked, “After Avedon, who is there?”

Up onstage it was the golden age of magazines, when one powerful man set legions in motion. And yet, I couldn’t help but notice, the stars were all of a certain age, pushing or past 60. Crack, Avedon: Even the references are from a past era. And yet for a night, the past and Newhouse are in their glory. His dark mood lifted.

That night, Backpacker magazine matched The New Yorker’s three awards.

“I better get an outdoor editor,” Remnick whispered to Newhouse.

“Yes, escape seems to be the thing,” Newhouse replied.

Additional reporting by Ross Kenneth Urken.