The first time I entered ChatRoulette—a new website that brings you face-to-face, via webcam, with an endless stream of random strangers all over the world—I was primed for a full-on Walt Whitman experience: an ecstatic surrender to the miraculous variety and abundance of humankind. The site was only a few months old, but its population was beginning to explode in a way that suggested serious viral potential: 300 users in December had grown to 10,000 by the beginning of February. Although big media outlets had yet to cover it, smallish blogs were full of huzzahs. The blog Asylum called ChatRoulette its favorite site since YouTube; another, The Frisky, called it “the Holy Grail of all Internet fun.” Everyone seemed to agree that it was intensely addictive—one of those gloriously simple ideas that manages to harness the crazy power of the Internet in a potentially revolutionary way.

The site activates your webcam automatically; when you click “start” you’re suddenly staring at another human on your screen and they’re staring back at you, at which point you can either choose to chat (via text or voice) or just click “next,” instantly calling up someone else. The result is surreal on many levels. Early ChatRoulette users traded anecdotes on comment boards with the eerie intensity of shipwreck survivors, both excited and freaked out by what they’d seen. There was a man who wore a deer head and opened every conversation with “What up DOE!?” A guy from Sweden was reportedly speed-drawing strangers’ portraits. Someone with a guitar was improvising songs for anyone who’d give him a topic. One man popped up on people’s screens in the act of fornicating with a head of lettuce. Others dressed like ninjas, tried to persuade women to expose themselves, and played spontaneous transcontinental games of Connect Four. Occasionally, people even made nonvirtual connections: One punk-music blogger met a group of people from Michigan who ended up driving eleven hours to crash at his house for a concert in New York. And then, of course, fairly often, there was this kind of thing: “I saw some hot chicks then all of a sudden there was a man with a glass in his butthole.” I sing the body electronic.

I entered the fray on a bright Wednesday afternoon, with an open mind and an eager soul, ready to sound my barbaric yawp through the webcams of the world. I left absolutely crushed. It turns out that ChatRoulette, in practice, is brutal. The first eighteen people who saw me disconnected immediately. They appeared, one by one, in a box at the top of my screen—a young Asian man, a high-school-age girl, a guy lying on his side in bed—and, every time, I’d feel a little flare of excitement. Every time, they’d leave without saying a word. Sometimes I could even watch them reach down, in horrifying real-time, and click “next.” It was devastating. My first even semi-successful interaction was with a guy with a blanket draped over his lap who asked if I wanted to “jack of” with him. I declined; he disconnected. Over the course of an hour, I was rejected by what felt like a cast of thousands: a teenage girl talking on her cell phone, a close-up of an eyeball. It started to feel like a social-anxiety nightmare. One guy just stared into the camera and flipped me off. Another stood in front of his computer making wave motions with his hands, refusing to respond to anything I typed. One person had the courtesy to give me, before disconnecting, a little advice: “too old.” (I’m 32.) A girl with heavy makeup looked terrified when my image popped up on her screen—I actually felt guilty, a few rounds later, when the engine of randomness threw us back together and she had to look at my face for another excruciating half-second. My longest exchange was with a guy who seemed to be wearing one of those protective cones you put on a dog after surgery. “LICK YOU ELBOW,” he typed. “Why?” I asked. He disconnected.

I got off the ChatRoulette wheel determined never to get back on. I hadn’t felt this socially trampled since I was an overweight 12-year-old struggling to get through recess without having my shoes mocked. It was total e-visceration. If this was the future of the Internet, then the future of the Internet obviously didn’t include me.

Although ChatRoulette feels radically new, it’s built entirely out of recycled parts—it’s just a potent combination of programs we’ve all been familiar with for years. Web chat has been around since the beginning of the Internet. Skype made the Star Trek–like experience of instant synchronized video communication an everyday reality back in 2003. But these experiences were almost always curated: The point was to chat and Skype with co-workers and friends, or at least with strangers who shared your interests. The internet has always been defined by (and drawn much of its energy from) the tension between chaos and control—and over the last ten years, web culture has skewed heavily toward control. Our most popular new online tools—Google, Facebook, Tumblr, Twitter, Digg—were designed to help us tame the web’s wildness, to tag its outer limits and set up user-friendly taxonomies. ChatRoulette is, in this sense, a blast from the Internet past. It’s the anti-Facebook, pure social-media shuffle. It arrived quietly last November, with no fanfare. (Given the nakedness of the ChatRoulette-user experience, it’s interesting that the site’s founder is unknown; web searches lead back to a Netherlands-based anonymity service.) Once you dive in, there’s no way to manage the experience—to filter users, search for friends, or backtrack and reconnect with someone you chatted with an hour ago. There’s only the perpetual forward motion of “next.” It’s the Wild West: a stupid, profound, thrilling, disgusting, totally lawless boom. If ChatRoulette catches on, it might even swing our collective online pendulum back toward chaos.

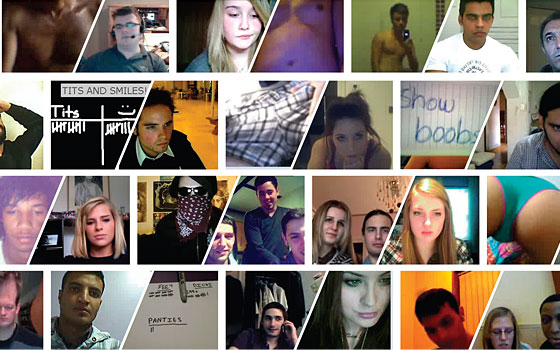

There’s a reason, of course, that we’ve worked so hard to tame the web. Wildness can be terrifying. A site like ChatRoulette raises all kinds of potential dangers. Garden-variety Internet nastiness is suddenly supercharged: Anyone who gets a thrill from lobbing snark will get an extra thrill from watching people react. (If I were still an unpopular 12-year-old, my first ChatRoulette session might have crushed me for a year instead of just an hour.) Then there are privacy issues—people taking screengrabs of other users in the half-second they happen to be looking at a pornographic image, then spreading them around the web. (I’m sure there are at least 300 images of me wincing at a masturbating stranger.) Sexual predators have never had an easier way to expose themselves, potentially even to children (the site has no apparent age limit). And then there’s the threat of violence. One popular shock image, a picture of a man who’s hanged himself, is terrifying even after you realize it’s fake: It makes you think about the possibility of someone actually hurting themselves, or someone else, in the unmappable ether of social-media space.

A few hours after my first ChatRoulette session, one of my actual physical friends came over to my actual physical house. I told him all about my horrifying experience that afternoon—the insults, the masturbators, the searing flashbacks of adolescent shame. He demanded that we get on the site immediately. Somehow, with two people, the experience was different—the rejections less intense, easier to laugh off. We ended up staying on, talking and dancing, connecting and disconnecting, for four hours. We chatted with Pratt students in Bed-Stuy, with a man inexplicably sitting on his toilet, with a kid waving a gun and a knife, and with a guy who went to my wife’s old high school in California. We saw Chinese kids in computer cafés and English kids drinking beer. We danced with a guy in his bedroom to the entirety of Michael Jackson’s “Don’t Stop ’Til You Get Enough.” We talked for half an hour with a 28-year-old tech writer from San Francisco.

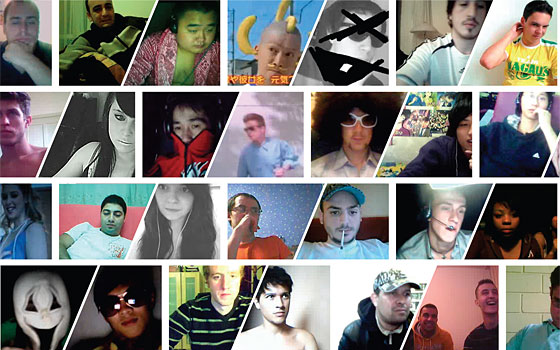

After a while, I started to get the lay of the land. The median age seems to hover around 20, and males outnumber females probably twenty to one. Sex is ever-present, whether insinuated or enacted. (My wife sat in front of the webcam for a while, and it was suddenly, disturbingly, a much friendlier world.) People are endlessly soliciting nudity, both in person and via signs (“FLASH TITS FOR HAITI,” etc.). Roughly one out of every ten chatters is a naked masturbating man, and even they will usually hang up on you, one-handedly, before you can click away.

YOU: yo man

YOU: like your glasses

STRANGER: thanks

YOU: where are you? on a boat? or is that a bunk bed?

STRANGER: CHINA and you?

YOU: NYC USA

YOU: nihao!!

YOU: i learned “nihao” from a cartoon

STRANGER: yeah 你好~

YOU: okay, have a great night! i have to go to bed!

stranger: yeah good night

you disconnected. looking for a random stranger …

The default interaction on ChatRoulette is roughly three seconds long: assessment, micro-interaction, “next.” This might seem like yet another outrage of the Internet era—the Twitter-fication of face-to-face interaction. But I was surprised (as I was with Twitter) by how much pleasant communication—joy, interest, empathy—can occur in these tiny chunks. The quest to connect becomes lightning-quick. A few seconds is plenty of time to wave, or give a thumbs-up, or type “EMO HAIR,” or elaborately mime the process of smoking marijuana, or jovially flip somebody off. (Middle fingers are extremely popular on ChatRoulette, and somehow seem affectionate.) The paradox of face-to-face conversation across vast distances seems to do strange things to the human brain. I often found myself acting unlike myself: dancing without provocation with a roomful of Korean girls, greeting people with flurries of over-the-top marijuana slang even though I’ve never even smoked a joint.

As Internet culture has grown, we’ve come to romanticize certain kinds of unmediated, old-fashioned “human” interactions. But this fantasy ignores how much of normal social interaction is fleeting, bite-size, instant, tweetlike. Humans have always talked to each other via a kind of analog Twitter. These new technologies just get us there with maximum efficiency. Meeting a new person is thrilling, in a primal way—your attention focuses completely, if only for a nanosecond, to see if the creature in front of you has the power to change your life for better or worse. ChatRoulette creates this moment over and over again; it privileges it over actual conversation. Eventually, I realized that clicking “next” was not so much a rejection as it was pure curiosity, like riding a train past an apartment building at night, looking briefly into as many lit windows as possible.

It’s hard to predict whether ChatRoulette will become a full-blown viral phenomenon, let alone an era-defining touchstone like YouTube. After that first magical night, I came down with an acute case of ChatRoulette fatigue. It felt like I’d experienced the full range the site had to offer: the shock porn, the dance parties, the weirdly aggressive homoerotic banter. I’d seen every dorm room in America, China, South Korea, and Brazil. I’d been called an old man more times than I could count. (My friend, who’s 37, was accused of being 90 years old, as well as a “kiddie diddler.”)

I found myself fantasizing about a curated version of ChatRoulette—powered maybe by Google’s massive server farms—that would allow users to set all kinds of filters: age, interest, language, location. One afternoon I might choose to be thrown randomly into a pool of English-speaking thirtysomething non-masturbators who like to read poetry. Another night I might want to talk to Jets fans. Another night I might want to just strip away all the filters and see what happens. The site could even keep stats, like YouTube, so you could see the most popular chatters in any given demographic. I could get very happily addicted to a site like that.

But that site would also lose a lot of what makes ChatRoulette, for now, so weirdly magnetic. If I’d been able to curate my experience, I might never have had what ended up being my favorite interaction: a half-hour chat with a twentysomething, vaguely Kurt Cobain–ish guy in Pittsburgh. We started with the obligatory ganja jokes, but suddenly he turned serious. “Actually,” he typed, “I’m a mystic.” When he offered me a tarot-card reading, I considered clicking “next” in search of more dancing Koreans. I’ve never had a psychic reading—in fact I’ve actively refused them on many occasions—but something about the strangeness of the context made me accept. Although I only vaguely remember the content of the reading itself (I like nature, have been thinking about taking a big trip, etc.), the experience was surprisingly powerful. It felt generous and deep and oddly very human. Maybe it was just the gift of sustained attention in the midst of so many disconnections. Afterward, he told me that his name (like mine) was Sam, although he called himself the ChatRoulette Mystic. He said he liked to think of himself as a “social-media artist”: In the same way that a painter’s canvas, say, can affect the emotions of a museumgoer, he wanted to affect chatters’ emotions through his webcam. It was exactly the kind of New Agey thing I’d probably make fun of in my actual, offline life. And yet I knew exactly what he meant. When he asked if I would spread the word to my friends, I told him I would do my best.