It was the perfect letter—if the goal was to blow up New York society. A bombshell of preening and aspiration, it set off a war between an aging princess and the girl who threatened to snatch her crown. There was just one catch: According to a complaint filed last week with the Manhattan district attorney’s office, the letter was a fake.

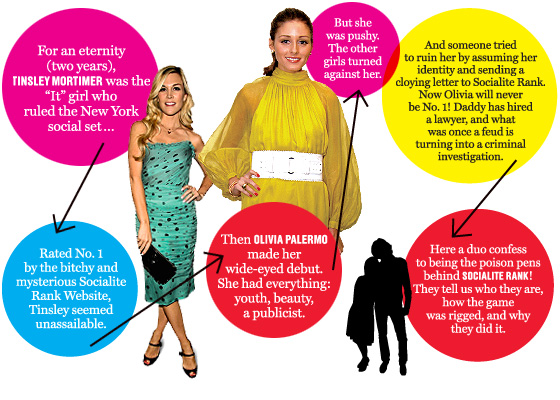

The publisher of the letter was socialiterank.com, a mysterious Website that appeared on April 24, 2006, declaring itself unofficial judge, jury, and executioner of 10021—the Zip Code of upper Park Avenue and Fifth, and the home of many young women who appear on the charity-ball circuit. Each fortnight, the Website released a “Social Elite Power Ranking,” scoring the women on their personal style, public appearances, and publicity efforts. The perennial No. 1 girl was Tinsley Mortimer, a Virginia rug salesman’s daughter who had married into New York society.

The Website took an ominous tone from the start. “Next time you think about skipping that certain gala, wearing that unknown designer, dating some weird band member, beware,” it warned. “We’re watching. And your ranking is on the line!” In the year since it appeared, Socialite Rank manipulated the city’s gossip cycle, elevated unknown women to unlikely prominence, and gained thousands of readers, who filled the comment boards with catty and frequently venomous remarks. Several socialites were mocked and ruined, others smeared with rumors of cocaine abuse. And what made it more eerie—like the voice of a Bitch God bellowing from the heavens—was that no one knew who was speaking: The Rankers hid behind their anonymity, as did the commenters who wrote in with their own harsh judgments.

As Socialite Rank gained prominence, it found its ultimate target in Olivia Palermo, a wide-eyed New School student who had hit the charity circuit in tight dresses and loose ringlets around the time of the site’s launch. At first she was warmly received, but gradually she began to offend. During Fashion Week in February, Olivia, just 20 years old, sat in the front row of so many Bryant Park shows that she became known as a potential threat to Tinsley, the reigning princess. Almost instantly, Socialite Rank turned on Olivia, pelting her with nasty remarks.

On March 27, the site posted a breathless headline: EXCLUSIVE! OLIVIA PALERMO LOSES HER MIND AND SHOCKS SOCIALITE WORLD. The accompanying story claimed that Olivia—“our social climbing heroine of the moment”—had written a letter apologizing for her sycophantic ways. According to the site, she had e-mailed 70 prominent socialites to beg “for acceptance, privacy and forgiveness.” The Website also claimed that the e-mail was being forwarded all over town, with recipients claiming it was “desperate,” “crazy,” “idiotic.” But what angered socialites—or allegedly did so—only excited Socialite Rank, which instantly delivered its own “final verdict”: Olivia Palermo had been officially evicted from the club. “This is better than Ecstasy,” the Website gushed.

“Dear Ladies,” the “Palermo letter” began. “I know I have gotten off on the wrong foot with many of you and there may even be some of you that do not like me. But I feel that those feelings are more a creation of websites like socialiterank, rumors and gossip than they are to your own experiences.” The writer went on to reintroduce herself as a student, an athlete, and a “great shoulder to cry on” who hoped for nothing but forgiveness and friendship, perhaps a spot on a charity committee, and eventually a friendly hello if she dropped by the Waverly Inn. “Lots of love,” she closed.

Olivia instantly denied writing the letter, which Socialite Rank claimed she sent from a Yahoo account that Olivia said she never owned. Not only that, Olivia said, the writer of the letter had stolen her identity. She planned to hire a lawyer. The announcement evoked howls. “She’s turning into the Anna Nicole Smith of the benefit circle,” one social observer quipped. “A tawdry, trashy, white-trash circus freak.” But Olivia was serious. “I may be a young girl,” she told another socialite, “but behind every young girl is a powerful father.” Quietly, her father, Douglas Palermo, a successful New England real-estate developer, hired one of the nation’s premier litigation firms.

One month later, on April 26, Socialite Rank ran its final post. “SR is closing its society heaven,” the Website announced. After urging readers to take a deep breath and focus on the screen, Socialite Rank’s founders claimed they hadn’t shut down owing to “lawsuits, complaints or threats.” In fact, they had always planned to publish for a year and no more. Now, having gathered “behind-the-scenes triumphs, power struggles, love affairs,” and “many more unpublished ‘Palermo’ letters,” they would compile the results in a book, tentatively titled The Year of the Rank. Around noon on Sunday, April 29, the Website went blank.

The charity circuit, once a bastion of breeding and privilege, has transformed itself, in the days since 9/11, into a kind of reality show. Running from September through May (and ending with the Met’s Costume Institute Benefit Gala, which takes place this week, on May 7), the parties raise funds but also provide an extended publicity campaign for young women who seek to become famous. They compete in a gossip free-for-all played out in tabloids and on the Internet. In this mediated world, public image cuts dangerously close to private reality, and it is considered an honor to have one’s photograph rudely dissected on a Website.

The business of rising from social girl to professional celebrity was put into overdrive five years ago by Paris Hilton. Rising alongside digital cameras and photo blogs, she constructed a life based on hype and a pretty face. What a strange fascination this young girl has with getting her picture taken, thought David Patrick Columbia, editor of the New York Social Diary Website, as he watched her gyrate for Southampton cameramen. Now he reflects, “It turned out to be a major career! She’s a multi-million-dollar personality, and it’s all because of having her picture taken—nothing else. She is the equation.”

Hilton preferred the word heiress to socialite, but in fact she embodied the original meaning of the latter term, coined in 1928 by Briton Hadden and his fellow editors at Time to describe the rebellious young women of the Jazz Age. A socialite was brisk and blithe, radiant and unconcerned. She embodied youth, freedom, modernity. When Hilton left for L.A., finding fulfillment as a reality-show star, she was succeeded by a generation of girls—perhaps 100 at the core—who wished to repeat her success, without taking off their underwear. A peculiar amalgam of some of the oldest names in New York, daughters of captains of industry from all over the world, and pretty young things with the right dresses but no pedigree at all, these girls proudly called themselves “socialites.”

Their leader, Tinsley, had debuted at the cotillion in Richmond, Virginia, and attended boarding school at Lawrenceville, in New Jersey. After graduating from Columbia, she married her high-school sweetheart, “Topper” Mortimer, and then hit the charity-ball circuit with her sister-in-law, Minnie. Breathless, bubbly, Tinsley wore short, baby-doll dresses cinched at the waist and fanning out mid-thigh. When posing for pictures, she liked to open her mouth, arch her neck, and wink at the camera, like a virgin holding a secret.

Tinsley and her sidekicks and associates—the Venezuelan heiress Fabiola Beracasa, the daughters Hearst, assorted ugly ducks and pretty young things—quickly filled the gossip news hole that Paris had left in her wake. “I’d rather cover sports stars and celebrities,” says Daily News gossip reporter Patrick Huguenin. “But, on a slow day … ”

Socialite Rank had no such snobbery about the relative merits of the homegrown party scene. The Website broke down socialite party performance into four categories: “personal styles and designer relations”; “press coverage in major publications and gossip columns”; “appearances and commitment to events”; and “hot factor—what makes each of the individuals sizzle with personality.”

Tinsley nearly always scored first and Fabiola second. Like high-school cheerleaders who tire of their boyfriends, sometimes they traded places. But there was more to the site than simple competition. It featured pictures of pretty girls, the promise of impending tears, and the threat of public humiliation. The most rabid readers were the socialites themselves. Asked to submit their favorite designer, travel spot, and astrological sign, many responded immediately.

Socialites were glued to the site. Some checked it every few minutes. Dozens were brought to tears. “We’re all human, my God,” says Zani Gugelmann, the No. 4 girl. “Who wouldn’t cry when somebody says they’re fat or they have a horse face or a big nose? You’re like, What? And that’s just the physical stuff. When they say nobody likes you, it’s shattering.” Lydia Fenet, a benefit auctioneer for Christie’s, logged on to find herself accused on two counts: being a social operator and having a horse face. “She cried for days,” one friend recalled. “But because of that site, she’s a huge social star.”

Soon the process gained momentum. Women made reputations and lost them, stimulating greater interest in the social scene and attracting reporters who trolled the site for new profile subjects. One element the scene lacked was a fresh face. Tinsley, after all, was entering her thirties. “The media is just carnivorous about these women,” says her brother-in-law, Peter Davis, a columnist for the uptown magazine Avenue. “They crank them out—it’s like a machine—and then they want a younger one, they want a new one, they want a fight.”

Staring into this house of mirrors was Olivia Palermo, a young girl bewitched by her own reflection. The daughter of a real-estate developer and an interior decorator, she had grown up on the Upper East Side and in Greenwich, Connecticut. She had all the requisite trappings: the private-school education at Nightingale, Windward, and St. Luke’s; the party frocks from Bonpoint; the year abroad in France. Now she wanted to join the girls she read about on Socialite Rank.

She began interning at the society magazine Quest, dropping pounds, and seeing more of her childhood playmate, the actor-heiress Byrdie Bell. In April 2006, Byrdie’s mother took the girls to a Sotheby’s auction. Olivia wore a blue dress and a white belt; Byrdie, taller and larger-boned, paired a black dress with a denim jacket. They rushed over to Gugelmann, who was chatting with the party photographer Patrick McMullan. “Zani, Zani, how are you?” they asked. McMullan turned around. “Oh!” he said. “Who are these two pretty girls? Let’s take a picture.”

The next day, Olivia and Byrdie appeared on patrickmcmullan.com. “These are the new girls,” Zani wrote in an e-mail to a friend. “They’re going to be the next pretty young things.” A week later, Zani saw the girls at another party. “Realize what you’re getting into,” she said. “Once you’re in the public eye, people can toss you around like a ball. And you don’t know whose hands you’re going to land in.” The girls listened, nodded, and when Zac Posen invited them to his “Spring Fling,” they arrived in his dresses.

Olivia joined the social circuit in earnest that fall. Photographers were charmed and so was Socialite Rank, which asked her to submit a profile. (“Favorite Things I Simply Love: Manicure and pedicures.”) She didn’t land in the top twenty, but she reached the runners-up category called “Don’t kill yourself, you almost made it.”

Excited, Olivia increased her efforts. She hired a publicist, Dennis Wong at People’s Revolution. She met fashion designers. In January she joined charities including New Yorkers for Children, which funds the city’s child-services administration for low-income families. “It’s no Sloan-Kettering,” remarks a longtime scene watcher, “but because Anna Wintour is involved in that one, it could be your ticket into Vogue. And, most important, Olivia could get in. They accept anyone, if you have the money.”

The women proved less accepting, especially after Olivia made a few missteps. She said hi to some girls whose pictures she had seen on the Website but to whom she had never been introduced, or she rushed over to speak with them just as a photographer appeared. “She would hover,” one girl recalled, “in this very carnivorous way.” And when the photographer left, so would Olivia—only to appear in front of the same camera, next to another girl. She moved too fast, at parties and in the scene, becoming known as the Pop-up Socialite. “She’s given up all the pleasures of youth to pursue her goal,” one girl jeered, “like a kid in a pageant.”

The tension came to a head in February, when Olivia made her grand splash at Fashion Week. “Page Six” ran a gossip item saying Tinsley would pout when asked to pose for pictures beside Olivia. The social world took sides. Eric Wilson wrote a feature piece for the New York Times’ Sunday “Styles” section featuring a prominent quotation from a young man on the scene, Kristian Bravo Laliberte. “She’s past the point!” he declared of Tinsley. “She’s becoming Paris Hilton!” Socialite Rank retaliated, calling him a “D-list leach” and crossing out his photo with a pink X. Commenters piled on.

On February 28, Olivia threw a birthday party. She was turning 21. It was an intimate affair—twelve best friends and one member of the press, sipping Champagne and slurping corn soup at Bruschetteria on Rivington Street. “Everyone had their little name plates, and everyone gave their prezzies,” Olivia’s friend Chessy Wilson recalls. “It was cute!” The celebration continued on March 2 with a bash at the nightclub Marquee. The invitation featured Olivia’s face against a starry black backdrop.

A few days later, Socialite Rank parodied the invitation with an “SR Creation”: Olivia on a can of tuna fish. “If you haven’t heard Olivia Palermo’s name over the last week in a half you probably still in the severe state of trauma over Anna Nicole’s death or reside in some Third World Country where the only access to the Internet is available through one computer at the central Red Cross,” the Website remarked in its oddly ungrammatical voice, then went on to accuse her of borrowing dresses, skipping class at the New School, and copping an attitude of “aimless desperation.” SR asked its readers: “Is she a packaged can of tuna, a Chicken of the Sea?”

The article struck a nerve. Hundreds of readers posted replies. “She is so boring, lame, and has nothing to offer,” one wrote. “She’s quite the climber and clings to the top girls. She is a sad wannabe. she should go to school and go away. no one really wants to talk to her or knows what she’s even doing.” A more perceptive commenter wrote, “Build them up and then tear them down that’s how this world goes. Welcome to the top, bitches—it’s a long way back down.”

Three weeks later, the Website attacked again—printing the letter. Olivia kept her chin up, hosting a party for her boyfriend Brad Leinhardt’s fashion line, Izzy Gold, dining on truffle fries at Bette, storming the Room 100 magazine party at 60 Thompson. Almost no one in the room spoke to her, but she said such slights didn’t matter. “I have 400 friends in my BlackBerry and I get more invites than I can handle,” she said to me, taking my call. “All I care about, quite frankly, is that someone is pretending to be me. Can I call you back in a little bit? We’re just finishing up lunch. Toodles! Bye!”

Fake or not, the letter had all the elements that drive Web traffic and create tabloid intrigue: youth, beauty, wealth. The Post ran an item titled YOUNG BEAUTY: BE NICE TO ME! Then “Page Six” got a second day out of the scandal, this time printing Olivia’s denial. (“Again!” one socialite huffed. “With a picture!”) With each story, Olivia’s reputation sank within the social world, but outside of that small circle, she attracted sympathy. “Now she’s at the center of everything,” the fashion designer Holly Dunlap said. “This whole incident has created an Olivia fan club. Everyone’s cheering her on.”

As Olivia’s fame spread, the women she was leaving behind began to speculate about who had written the letter. There are four basic theories. Theory 1, which can be dubbed “The Idiot,” has it that Olivia sent the letter in total sincerity, wishing to befriend the girls who had rejected her. Most ignored this theory on the grounds that Olivia would have to be “idiotic” to send the letter. The second theory, “The Fat Bitch,” is based on the notion that, at the bottom of every scandal, you will find a single individual nursing a grudge, often an overweight woman. “I’ll tell you who did it,” a social observer told me. “Some jealous fat bitch. There are some vicious shrews in this town who don’t want to share camera time. They aren’t socialites, but they don’t want to be knocked off their faux-socialite pedestal.”

As newspaper and blog readers gave credence to the Fat Bitch theory, the socialites themselves put out a third theory, “The Counter-Fake.” According to this theory, Olivia and her PR team had written the letter as a media stunt, knowing it would be unmasked as false, to play into a Mean Girls story line. “They faked the fake!” one socialite told me. “I was told this by somebody on the inside. It was very clever. Everyone is feeling sorry for her right now. ‘Oh, the poor girl! Why don’t they just let her be a socialite?’ Well, I don’t think there’s anything to feel sorry about. She got exactly what she wanted: attention.”

The fourth theory, “The Pawn Gambit,” is the most paranoid. According to this notion, Olivia’s PR team knew that New York was planning a story about her, and they worried that we found her “boring.” So they crafted the false story line of a rivalry with Tinsley, hoping to rocket Olivia to fame. “All of New York Magazine fell right into the trap, and they’re prepping the world for your 5,000-word story by getting that little girl’s face in the newspaper every day,” one socialite told me. “You’re just the pawn in their frickin’ game!”

As Olivia’s name hit the Post, the Daily News, and Radar Online, Tinsley, who subscribed to the Counter-Fake theory, grew angry with Olivia. Tabloid reporters, however, threw their weight behind the Fat Bitch. They wanted a rivalry—the blonde and the brunette, the favorite and the upstart, the Wasp and the Vowelista. Olivia could play Veronica to Tinsley’s Betty. The story line would damage Tinsley’s name and bring unwanted attention to her age. But in the end, she would unwittingly bolster that narrative.

On April 2, the two girls separately arrived at the nightclub Capitale to model in a fashion show. It was the night of the annual Scottish party Dressed to Kilt. Upstairs, where the girls were changing into plaid, the room was swarming with the tabloid press and publicists. Olivia sat quietly in a white slip, texting on her BlackBerry as hair helpers sprayed her down. Tinsley, Manhattan in hand, tried to unwind—and steer clear of Olivia. It was tense.

Downstairs, in the crowd, men in kilts were getting wasted. The socialites did their turns and lined up backstage for the final walk. One by one, they passed down the runway. Olivia turned, walked backstage, and headed up the stairs. Just as she trotted up the right side, Tinsley came down the left, preparing to do her final turn. Staring straight ahead, she stiffened her left shoulder and appeared to knock into Olivia, who stumbled into the railing. “Oh, my God,” a girl behind Olivia said. “I can’t believe it!”

The next day, the tabloid press reported the alleged event, as well as Tinsley’s denial: “I never came within an arm’s length of her.”

Socialite Rank covered the incident by not mentioning it at all. Instead, the Website quoted an e-mail that it claimed originated with one of the show’s coordinators. “Olivia looked stunning” was the judgment, “but no one really knew who she was. She barely received any applause. Tinsley really worked it and it showed.”

By the middle of April, many of the women had fled the circuit. They stayed home and had dinner parties away from the cameras. At charity events, paranoia set in. “You never know who you’re talking to,” one socialite said. “You could be talking to somebody who could write something terrible. They probably already have.” Socialites speculated about who could be behind the Website. They threw names about at random. Some, once fingered, had to make multiple denials. One girl called it “a witch hunt.”

Suspicion centered around three groups of suspects. Most thought the writer Derek Blasberg, who had left Vogue for a career as a freelancer, had founded the site along with a few collaborators, perhaps including his friend Lyle Maltz. Tinsley Mortimer’s brother-in-law Peter Davis ran a close second. “Don’t you know?” he joked to friends. “I’m the one who runs Socialite Rank.” But that pesky matter of the Website’s oddly ungrammatical voice kept arising. An inner circle of socialites began to suspect Fashion Week Daily reporter Valentine Rei and his stepsister, Olga Rei. The teetotaling Russians arrived on the scene three years ago, party crashers cadging invitations, handing out business cards, and sidling up to the most famous people in the room.

They look like twins and opposites: Valentine is tall, blond, and reedy, with a skinny chest and dangling arms; Olga is blonde, too, but busty, standing barely five foot four inches. They don’t drink, don’t smoke, but they’re addicted to fame, having sought it out at a young age. They were child stars in Russia, where they met and grew up together, after Valentine’s father married Olga’s mother. Valentine was a host for the Miss Moscow pageant at the age of 7, then he appeared on game shows; Olga was a V.J. on Russian TV. “It’s almost like destiny,” Valentine says, “for us to be intertwined.”

Moving to New York in 1995, Olga and Valentine attended artsy La Guardia High. They are from a wealthy family—each summer they sun in Hella, Iceland, where Olga keeps her two favorite horses, Beyoncé and Rod Stewart—but they quickly fit in with the sketchpad dreamers and theater geeks of La Guardia. Inspired by the school’s annual Halloween parade, the duo began hosting a party of their own. Last October 31, they draped Bungalow 8 in black and gold. Fabiola arrived in body tattoos, Tinsley as Strawberry Shortcake.

Suspicions that Olga and Valentine secretly ran Socialite Rank grew gradually. “They were wannabes for a long time,” one fixture in the scene says, “and sometime or other they started acting like they were somebodies.” On Socialite Rank’s final post, “The Year of the Rank,” Olga’s face appeared in a gallery that included all the top girls except Olivia. “One of these things is not like the others,” said Peter Davis.

I first met Olga and Valentine in early April, at Ono in the Gansevoort hotel. It was pouring rain and we hunched together over cast-iron teapots, sipping from hot mugs of cardamom tea. Valentine wore a sling; he had recently broken his elbow when he fell off the runway at a Y-3 Fashion Show—for a Fashion Week Daily reporter, the equivalent of a Purple Heart. Olga, an account manager for Lippmann Advertising, shares Valentine’s drive. At 23, they’ve already helped launch a glossy fashion magazine, Quadrafoil.

We ordered some dumplings and began to talk. The cosmically connected kids—born just three days apart—talked about their unconscious harmony, often completing each other’s sentences. I asked how they saw themselves in this world. “Powerful people control famous people,” Valentine said. “That’s what we want to be.”

I brought up socialites. Valentine told me there are socialites in Russia, too, only there they are called svietskiyi lvitzi—social lionesses. “Think Tinsley,” Valentine said. “But the hair’s going to be bigger, longer, more luxurious.”

He tried to keep cool but grew excited as he talked. “Socialites today have everyday jobs. But—in the evening they go out, they wear fancy dresses,” he said. “They’re regular people living celebrity lives, and that’s what makes them so exciting.”

“It’s true,” Olga said. “Everyone works so hard … I work with Damon Dash, him and Rachel [Roy], and Rachel is becoming more and more prominent.”

“When you actually speak to her,” Valentine said of Roy, “she’s very intelligent, very educated.”

“And I can’t believe she’s a mom too!” Olga said.

“And a stepmom!” Valentine said.

“A mom, a designer, a personality,” Olga concluded. “That’s what I’m saying! They think all we do is put a dress on and go to a party. The reality is, we work all day—then we put a dress on.”

“We’ve been friends with celebrities before we were friends with socialites,” Valentine said, “but I think socialites are more fun, easier to hang out with.”

I asked them about Olivia. “She’s a nice girl with nothing to say,” Valentine said. “A quiet little pedestrian college girl. But she obviously wants to be in the spotlight.”

“She hasn’t paid her dues,” Olga said.

Because their opinion so closely mirrored that of Socialite Rank, I asked them directly: Did they run the Website? Valentine flinched, stiffened, and looked away. Olga blushed.

“It’s changed the mentality of New York over the last year or so,” Valentine said.

“Thank God they haven’t said anything negative about us!” Olga added.

“You’d have to be delusional to attach yourself to a Website,” Valentine averred, “but of course there have been rumors—”

“I think there’s a rumor on every single person who is on that Website,” Olga said.

“My theory,” Valentine concluded, “is they live in New York, but they’re a person who doesn’t have any prominence. I feel like it’s going to be somebody no one’s ever heard of.”

“They do get a lot of scoops, though,” Olga said.

“It’s going to be somebody people don’t expect,” Valentine said. “An unknown freelance journalist.”

One month later—two days after their Website went blank—they decided to tell their story. When presented with a paper trail that appeared to link Socialite Rank’s electronic address to their billing address, they decided to confess. Why not? More fun! It was impossible not to consider, in this house of mirrors, that I might be falling for the ultimate fake, but their confession poured out: detailed and—to all appearances—deeply felt. “We are the masterminds behind Socialite Rank.”

We shared tapas at a small wooden table in the back of an empty downtown restaurant. It was pouring again, with a full moon on the way. Olga admitted to feeling “vibrations.” She smiled bravely when considering the past twelve months, as did Valentine. “Two thousand and six was the year of the socialite,” he said proudly. “We’re just starting. You know we’re going to be like Rupert Murdoch.”

The next moment, he was worrying. “Everyone’s going to hate us!” he said. “We’re not going to be able to go to any parties. How will I cover events if I go to a party and I’m ten times more famous than Tinsley?”

Olga glanced sideways toward Valentine and batted her lashes. “Are we crazy?” She laughed, and then they started talking.

The idea arose last year, just before the Met’s Costume Institute Benefit Gala, as Olga and Valentine dined at The Four Seasons. They had fallen in love with the PYTs. They wanted to give the girls a platform, put them in lights—and have a little laugh at their expense.

“We’re not evil,” Olga assured me. “We just thought it would be fun.”

They agreed at the outset to run the site for a year and no more, no matter what. The idea took shape when they saw a New York Post article about hotness. The Post had invented a formula that calculated an individual’s total hot factor. “It was completely ridiculous,” Valentine recalled. “We thought it was obscene. But then we thought, What if we just rank the girls? And put the numbers next to them!”

Olga and Valentine sifted through the names of 170 women, from debutantes to ladies who lunch. “It was extremely fair. It was extremely mathematical,” Valentine said. “They go to the event, they look pretty, their event score goes up.” The response was overwhelming. It took the Website’s founders five days to read through their e-mail. Many letters came from socialites. “They started campaigning,” Olga said.

Publicists flooded the site with requests to post pictures and press releases. Swamped, the Russians obliged, often highlighting nonstop e-mailers like Lydia Hearst (who often tells the press she isn’t a socialite). “She wrote us more than anyone,” Olga said. “Once the girls got the fame,” Valentine continued, “their friends revealed their dark demons, their secrets—drug use, sexual pasts.” There were nice comments, too, some from readers in Dubai, many from 10021, and dozens of comments from Tinsley’s mother.

Tinsley wasn’t meant to be the site’s star. Olga and Valentine just happened to love the package: the smile, the wit, the handbag line. She was the picture of a socialite. “You need a hero, you need a face,” Valentine explains. “That’s Tinsley—the face of Socialite Rank.”

At the end of 2006, the site decided that Tinsley was Socialite of the Year. When Olga and Valentine bestowed upon their favorite face another high honor, an “SR Creation” known as the Silver Spoon award, Tinsley wrote back with a letter of praise and thanks.

“We created a community,” Valentine said. “People begged us to keep going. We had no choice.”

After a few months, they had to buy more server space. They bought a second allotment, and more again. Finally, they bought a domain name. It didn’t cost much: Their total expenses for the year were only $750. And sellout offers flew in: $175,000 to write a corporate blog; an hour on camera with Tyra Banks; TV shows, films, cover stories. The New York Times wanted to do an exposé. VH1 offered correspondent jobs. There was just one condition: They had to reveal their identities. They refused.

In the new year, more stars were born. Fabiola Beracasa, who began with a low profile, appeared at events perfectly dressed, exchanged hugs with Olga and Val, chatted, smiled, and hit No. 1. “Work it!” Olga exclaimed. Arden Wohl, the headband socialite, also rose in the ranking. “She’s been a downtown icon in our eyes for years,” Valentine said. “Now the other girls are catching on.” The ladies who lunch dropped off, and Rachel Roy, once unknown in 10021, clawed into the top five. “We gave her the title of socialite,” Valentine said. “It feels like everyone in the world benefited but us.”

But there is one girl who hasn’t benefited, yet. Olivia Palermo never climbed higher than the sixteenth spot. She broke into the top twenty with her looks, but she failed to impress Olga and Valentine with her skills in manipulating the press—namely, Olga and Valentine. Asked how she felt, she might say, “Like a kid in a candy store!” Asked about her dress, she might opine, “Girls love to play dress-up.” The canned statements annoyed Olga and Valentine. Besides, they didn’t lack for people to like. “Tinsley was one of our heroes,” explained Valentine. “You need villains too.”

“Canned,” “packaged,” Olga said to her production wizard, whose identity they are still protecting. He tried to translate her words into an “SR Creation.” Packaged, canned, he repeated to himself—and then thought, tuna fish. An idea was born. “We did that evil article,” Olga recalled, shaking her head. “And that was enough.” Readers got the story line, and the comment hordes pilloried their new villain. And then, the letter.

“We’re being honest,” Olga said. “We did not write the Olivia letter. But whoever did it, they are even smarter than us.”

Socialite Rank’s story—should we choose to believe it—is this: “It was not a vendetta against Olivia,” Valentine said. “It was a vendetta against us. Someone set us up.”

“We thought it was real!” Olga said.

“Three people forwarded it to us,” Valentine said. “So we posted it. We never thought it was going to blow up.”

But it did. The Website is dead; the servers have been taken offline. And whoever wrote the letter will not be hard to find if the D.A. takes Olivia’s case and brings to bear the power of subpoena. That is clearly the hope of Olivia’s attorney, Cyrus Vance Jr., the son of the former secretary of State and a partner with the law firm of Morvillo, Abramowitz, who filed a complaint last Tuesday with the district attorney of Manhattan. “Someone falsely represented him or herself to be Olivia Palermo in an e-mail letter posted on the Internet, in an attempt to injure, demean, and disparage Olivia,” Vance said in a statement. “That is the crime of criminal impersonation.”

Olga and Valentine, who have yet to hear from any lawyers, feel sorry for much of what happened—if not the idea itself, then the way they quickly lost control of it. Toward the end of our interview, I asked if they regretted founding the site. “What did we do it for?” Olga asked herself out loud. Valentine broke in. “The scary thing is—to us it was pretty effortless,” he said. “We’re wondering, what if we actually tried? Maybe we could be as big as PerezHilton.com? We could be ten times bigger! We have the power.”

And that’s what scares Olivia Palermo. But she wields her own kind of social power. A recent Wednesday night found her in the passenger seat of her boyfriend Brad’s red Miata, riding to the Anchor, a bar on the edge of Soho. I squeezed in, too, handing Olivia the gummy treats she wanted me to bring. (“Worms or bears??” I had texted back, and Olivia let me choose, simply writing “Spanks!”) We turned up the new Avril Lavigne song, and soon Olivia was seat-dancing in my lap, stopping to ask, “I’m not hurting your wanker, am I?” Brad donned his black leather driving gloves and zipped west to Greenwich and Spring.

Under the Anchor’s antler chandeliers, Oxford-shirt preps mixed with “gangstas” in oversize hats and gold bling. Olivia’s friend Theodora Richards blew smoke rings from atop a couch as her sister, Alexandra, selected records. Chrissie Miller, an owner and host, offered us a couch. Suddenly Olivia turned off the charm, appearing somber, withdrawn. “My tummy hurts,” she said, pouting. The new Mims song came on and the crowd swayed, and still she hardly moved. The carefree girl from earlier in the night was gone. “I rarely drink,” she announced, for the record.

She had learned, quickly, that the glittering house she had once aspired to enter was actually transparent. Anything that went on inside could become instantly, shamefully public. A few days later, while walking through Central Park, Olivia would confide to a friend that she needed a break and had decided to move, for a short time, to L.A. The conversation soon appeared on yet another anonymous rumor mill.

Socialite Rank was gone, but the day it shuttered a new Website assumed its place. “The Crown became ours this morning,” announced Park Avenue Peerage. “We give you this pledge: we will rule (and chronicle) justly.” Former Socialite Rank commenters immediately mobbed the boards. “It will be just like old times,” wrote a commenter who calls herself Countess Olenska. “Welcome me back, girls!” A commenter named Insider observed, “It’s the SR Reunion 2007.”

In the next few days, Park Avenue Peerage would acquire thousands of new readers. And then it would cause its own stir by profiling a girl who normally stays out of the party pages, preferring instead to surf Belle-Île-en-Mer. Jules Kirby, a “champagne-swilling” blonde, nearly blind in one eye, drove PAP commenters to the heights of hysteria. “Ooooh, Jules!” one gushed. “I love the fascination with the most useless people on the planet!”

Again, New York socialites began to speculate about who could be behind the Website. It was clear to all that PAP had to be run by the ultimate insider. An outsider never could have known about Jules. Most placed their bets on Kristian Laliberte, so obviously bruised by Socialite Rank and a member of the junior set often featured on Park Avenue Peerage. “It’s Kristian,” Valentine said. “Yes, it’s Kristian,” said Olga. “We’re 1,000 percent sure.”

But, as is always the case, the one revealing secrets is not an insider at all: He’s an 18-year-old college student who runs the site from his dorm room. “I live in Urbana, near a farm,” he whispers when I call. “Oh, my God! I’m not supposed to reveal anything. I’m like—I’m not even white! Do you know how fucking riotous this would be? I am not the poster child. You would not even believe what I look like.”

His name is James Kurisunkal. He’s a freshman at the University of Illinois whose fascination with society developed when he began surfing the Internet at the age of 9. The son of Indian immigrants, a library clerk and a nurse, Kurisunkal was precocious, but not in the usual way. He spent his adolescence reading The Book of Royal Lists. “I’m schooled in the Fields, the Swifts, the Pullmans, the Masons, the Armours, the Ogdens,” he says. “And then we have the Pritzkers and Crowns—oh, and I love the Boston Brahmins. I’m obsessed with them.” Suddenly, he interrupts himself. “Do I sound psycho? Do I sound like a loser? Like someone who didn’t make it? At the core, I’m a researcher. I’m an investigator.”

But he’s also, in a strange way, a member of society, at least what’s left of it. Because he makes inside information available to all—photos, family trees, skeletons in the closet—the girls have started writing to him, begging for prettier pictures, more-flattering articles, attention. James has never gone to a single charity ball. In fact, he’s never even been to New York. But he gets the e-mailed party invitations—and turns them down. He loves all the girls—Tinsley for being a legend, Fabiola for her personality, Lydia for her youth. It seems like they live in a nice house. But he would rather admire it from afar than walk inside.