Al Pirro looks exhausted. He’s coming down with something, he thinks. In press accounts, Al’s usually described as tan, but today his complexion appears yellow, almost nicotine-stained. “I’m worn out,” he says. He sits perfectly still, a small, elegantly dressed man (dark suit and black tasseled loafers) in a tall, straight-backed chair. We’re in his stunningly ordinary White Plains office, a few floors above the campaign headquarters of his wife, Jeanine, who is running for state attorney general. A minute ago, Al’s lawyer was sitting with us. Al dismissed him. He doesn’t need a minder. He needs to talk.

Since Jeanine, a three-term Westchester district attorney, announced her bid for attorney general, Al has emerged as perhaps the single most important campaign issue. He scored a couple of speeding tickets. And, as the papers won’t let anyone forget, he is a convicted felon. His trial for tax fraud also happened to disclose an old paternity suit against him. Then three weeks ago, there was the bombshell—but this time, it was Jeanine being investigated. She’d been talking to Bernie Kerik, the disgraced former NYPD commissioner, about bugging her own husband. She wanted to know if Al was cheating on her, with a friend of theirs, no less. Jeanine was caught on tape and investigated by the FBI, an embarrassment that somehow—again!—seemed like Al’s fault.

To Al, it’s the same dog-eared tale, endlessly retold for a couple of decades. Al knows how it goes: “Poor Jeanine. She could have been governor if not for Al.” Jeanine said as much on the tape. She should dump him, goes the chatter—chatter her campaign doesn’t rush to suppress. Why should it? This is Jeanine’s last political stand, and perhaps there is an advantage if Al is the bogeyman one more time. Perhaps Jeanine will emerge, like Hillary, a more sympathetic figure.

Al tells me he wanted to issue a press release. “You’d like to be able to return the volley once in a while,” he says. Al’s voice is so even, his tone so relaxed, he seems almost indifferent. He decided against a press release. “What good would it do?” he asks.

How about talking to Jeanine? They’ve been together for more than 30 years, and for most of that time, they seemed the self-completing power couple. She was the rising political star. He was the fixer who brokered the big Westchester real-estate deals and eased her political way. Together they threw those swinging parties at their mansionlike home, knocking back shots with the likes of Governor George Pataki.

“You can’t talk to each other?” I ask Al.

At 59, Al is trim, fit, and almost completely gray. He lets go a short, restrained laugh. “She’s out campaigning. I’m asleep by the time she gets home or I’m reading. And I don’t think that eleven o’clock at night is the time to sit down and talk about these things,” he says. “You’d never sleep.”

It appears that Al Pirro is lonely. The role of political spouse no longer suits him. Last summer, as Jeanine contemplated whether to run for the Senate against Hillary or for attorney general, Al offered his opinion.

“I didn’t want her to run for anything,” Al says. Jeanine’s political aspirations, he thinks, have done nothing but hurt him. In Al’s mind, the tax case “probably would’ve been a civil adjustment if you weren’t married to a district attorney.” Al pauses, then adds, “Look, the decisions that were made by her have a very significant negative impact on the economic status of our family.” And, as everyone should know, the family’s economic status is Al’s responsibility. “I was the person who dealt with being the breadwinner. I tell Jeanine, ‘You can’t enjoy the fruits of my hard work and destroy it at the same time.’ ”

“Meaning what?”

“Meaning she felt that she was an independent person; she wanted to pursue her career.”

“It wasn’t a compromise?”

“There are compromises, and de facto compromises,” Al says.

“This one was de facto,” I say.

“It was de facto,” Al says. He means it wasn’t a compromise at all. Al had no say in the matter. “You always hope for the best,” he says. “Sometimes hoping for the best is really not enough.”

I wondered about the speeding tickets, the female companions he is sometimes spotted with in Westchester restaurants. I’d spoken to a friend of Al’s who suggested this was Al’s cri de coeur, a way of asking Jeanine to pay attention to him.

“So that’s why I speed?” Al asks derisively. “So I can catch her attention?” Al is introspective; it’s surprising in someone usually depicted as an aggressive, blustery shouter. After a moment, he says, “The more clever question would be, Do you feel you’re acting out of some kind of inferiority because your wife is more accomplished than you?”

Perhaps it is the better question. What’s the answer? “The answer to that question,” Al says slowly, “is she’s not. I mean, she’s certainly more accomplished in terms of a person who wants to be on a stage, okay. But that’s not what I want. My applause will come from having the independence to go and do whatever I want, you know, in terms of my economic freedom.”

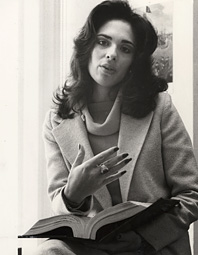

I wonder what Jeanine thinks. The following day, I meet the Republican candidate for attorney general at her office, ten floors below Al’s. We talk in her glass-walled conference room with its one small bookshelf—Practical Homicide Investigations is a title carefully placed there.

I tell Jeanine, who is 55, that I’d asked Al if he was acting out in order to get her attention.

“What did he say?! I want to know!” she says. I tell her Al’s alternative question: whether he felt eclipsed.

She purses her lips, steers her head slowly from side to side, as if to say, Isn’t that just like Al? “He’s a sharp guy, he’s smart,” she says.

Jeanine is intrigued. “Mmmm,” she says. “And then when he posited that, did you say, ‘Okay, answer it’?”

“What do you think he answered?” I ask Jeanine.

She barely hesitates. “Yes,” she answers brightly.

“Actually,” I tell her, “Al said no.”

“Really?!”

This, of course, is the season of political marriages (coming soon, the Pirros’ heavyweight Westchester neighbors, Bill and Hillary; Al and Carol Hevesi on the undercard). For Jeanine Pirro, everything is at stake. She trails in the polls in what may well be her last run for public office. She’s desperate to talk about her experience, her issues. And yet, for the viewing public, no spectacle is quite as riveting as the reality TV of feuding political couples. For a time, Jeanine and Al Pirro seemed as if they might avoid this kind of finale. After all, for a long time they appeared to be just the right pairing, the sum greater than its parts. He was the powerful real-estate lawyer with political juice. She was the bright, telegenic D.A., urged by nearly every Republican (including, recently, those in the White House) to seek statewide office.

Jeanine Ferris was from the small upstate city of Elmira, the daughter of a mobile-home salesman and a homemaker who constantly reminded her daughter of the importance of looking good. Jeanine’s story is one of transparent ambition. From the time she was 6, she told people she wanted to be a lawyer. “I was always in a rush,” she says.

Al’s upbringing in Mt. Vernon was scrappier. His mother was a waitress and problem gambler who squandered the family savings—they moved often, fleeing landlords. Al’s father, a former boxer, was a truck driver who valued toughness in his kids. When Al was 9, four older boys chased him until Al’s father stepped in. “He ordered me to fight all of them,” Al recalls. “It was total panic and fear. It was like that all the time.” Al was bright, that was his saving grace, and it made him the family’s hope, the one who, as Jeanine says, “would make enough to take care of everyone.”

Jeanine met Al at Albany Law School. “He was the most brilliant, energetic, high-powered guy on campus,” she says. “He was just dashing. He was the hardest worker I ever met.” Al held three jobs, including mopping classroom floors (and was also president of his class). Then on Friday nights, ten friends would assemble at a restaurant for dinner and Al picked up the check. “He was the most generous guy,” says Jeanine, who was seeing someone else at the time. Al approached her anyway. She was smart, delightful, and spunky, Al recalls, with long jet-black hair and sexy legs. “If we’re going to get married,” he told her, “we better start dating.” Al was only Jeanine’s second boyfriend; Al hadn’t had many steady girlfriends either.

“If you love somebody which … that was an earlier part of our life together …” Al starts to tell me, and then slips into a memory. “We were so closely tied together emotionally,” he says. “We always knew how the other felt. It was extraterrestrial.”

They married in 1975, and moved to Al’s territory, Westchester, a county then controlled by the Republican Party. Al soon established himself as a bright, aggressive, up-and-coming attorney. He worked as counsel for the municipality of Harrison, learning zoning law from the inside. Al says that success came because he worked so hard—overprepared is his word.

In short order, Al became the person to make a developer’s dreams come true. “He’s the lawyer developers hired to save their projects from the mire of bureaucracy or local opposition” was how the local newspaper put it. For a period, his name seemed to be attached to many of the important countywide projects, from the Westchester Mall in White Plains to the office parks in Mt. Pleasant to Home Depot in New Rochelle.

Al may have been a brilliant zoning lawyer, but his “juice,” as he sometimes called it, came through another route. “I learned that raising money was an important ingredient for political decisions,” says Al. “So early on, I would get together a group of businessmen. We would have a private dinner. We would invite a potential candidate or the county leader.” Soon, Al was in a position to dispense favors, an activity that, by some accounts, he took to with relish. Asked by a friend to help with an antagonistic public-relations firm in town, Al snapped, “I made him and I can break him.”

In Westchester, Jeanine landed a job as assistant district attorney, aided by Al’s political connections. She soon ran one of the country’s first domestic-violence units, becoming a champion of battered women and abused children long before it was a popular cause. Later she pioneered the prosecution of Internet pedophiles, pressing for legislation that gave her the enforcement tools she needed. Jeanine was bright enough to do the wonkish, heavy-on-fine-print, white-collar cases. But they didn’t captivate her. “I’m a fighter,” she likes to say, and her preferred opponents are those who commit, as she says, “crimes whose scars remain after the wounds have healed.”

Colleagues, she knew, suspected women couldn’t go for the jugular. And Jeanine was determined to prove she was made of steelier stuff. To her, criminals were “freaks” and “perverts” and “slime.” “Cage the bastard” was a phrase she used. Her job at the district attorney’s office was to sort out good from evil. “I don’t think we’re angry enough,” she says. Every would-be protector needs a steady supply of victims. For Jeanine, they were everywhere. “The line that separates those of us who are victims of crime from those of us who live carefree lives is a very, very thin line,” she once said.

In 1986, Jeanine’s name was put forward for lieutenant governor. Jeanine wasn’t much interested in political machinations. “I am astounded by the lack of interest she has in the ins and outs of Republican or Democratic affairs,” says Al. Fortunately, that was one of Al’s interests. “Do my relationships open doors for her in the GOP?” Al once asked. “Unquestionably.”

Then, on the eve of her nomination, a report circulated that Al was supposedly in a business with a mob tie. Jeanine declined to release a list of Al’s clients. Her name was withdrawn as a candidate, a turn of events that Al credits with initiating the theme of “Al as the problem.”

Jeanine was disappointed, but Al put his considerable energies to work on her behalf. “The best strategy I could put together for her would be to run for county-court judge,” he tells me. “Because in the county-court race, by the canons of ethics, they’re not really allowed to talk about anything other than the qualifications of the candidates.”

In Westchester, elections were a foregone conclusion. Republicans almost always won. The difficult part was getting the nomination. “The issue was really could I persuade the leadership to give her the nomination?” says Al. The local party was an old boys’ club; no woman had ever served as a county judge in Westchester.

Al, though, had been raising money for these guys for years. Plus, anyone familiar with Jeanine noticed her winning qualities. Al says, “She was a wonderful product for the Republican Party”—a party starting to recognize the importance of an energized female electorate.

Once Al secured her the nomination, Jeanine won in a landslide. Sadly, Jeanine didn’t particularly care for the job. “She was given the judgeship, and it was a disaster,” Al explains. “She was stuck up on that bench in a robe, ruling on cases. She hated it.” The post stymied her activist spirit, though the black robes were also part of the problem. She found them dreary. She sewed colorful linings inside the robes. “Sitting there all day in black, I’d flip it up and see a flash of color,” she says.

She and Al plotted her next step. “We started to support local candidates, state candidates,” Al once explained. “And a lot [of this was] establishing relationships so she could move on to higher office.”

In 1993, soon after the Westchester district attorney announced his retirement, Jeanine decided she wanted the job. With Al’s help, she won handily. Jeanine soon became the most famous district attorney in America. She had an aptitude for publicity. She was a D.A. who sometimes raced to the scene of crimes, making declarations to TV cameras, occasionally maladroit ones. (During a hostage situation, she declared that the criminal would face the death penalty, infuriating police working to get the hostages out alive.) Soon, she was on TV commenting on other trials. During O.J.’s criminal trial she “practically lived” on the set of Geraldo.

To her detractors, Jeanine’s prosecutorial zeal seemed a media stunt. She flew around the country, seeming to stalk Robert Durst, the Westchester millionaire suspected of murdering his wife, though no body was found. Jeanine flew to Texas and Pennsylvania—where Durst faced other charges—appearing on TV until a judge admonished her to shut up. Even Al thought it “warmongering.” “A lot of decisions she makes are made out of pure this-is-what-we-should-do,” he says. “If she would wait a day before she made some of these decisions, she would be a lot better off.”

Jeanine wasn’t likely to change. Her passion, her intelligence, and her instinct for the dramatic gesture were perfect for TV in a tabloid age. Plus, she looked great. She’d traded black robes for short skirts. Marking her celebrity status, in 1997, People magazine named her one of its 50 Most Beautiful people. Al seemed delighted. “There’s not a place I go where people don’t speak about my wife,” he said.

At home, life seemed equally exciting, for the most part. Pirroland could be an awful lot of fun. “I love to entertain,” Jeanine says. And they had just the spot: a $5 million Harrison mansion, which they built and designed to resemble a Venetian palazzo. They’d toured marble factories in Italy, selecting their favorites for the floors, for the stairs. “It’s marble on marble,” says one friend. Two Vietnamese potbellied pigs, Homer and Wilbur, got their own small house out back, penned in by an elaborate wrought-iron grill. (One visitor figured it was the servants’ quarters. The help, though, slept downstairs, near the exercise studio where Jeanine could sometimes be found before dawn.)

The Pirros held lots of parties. “A lot of dancing. A lot of entertaining,” says Jeanine. They hosted theme nights. Cowboy night, Mexican night. One friend remembers spotting the district attorney at the top of a marble staircase in four-inch Manolos and a bustier. “If you’ve got ’em, flaunt ’em like diamonds,” Jeanine explained.

It was a striver’s Camelot, a sexy, ethnic shindig where people like Joey and Cindy Adams and designer Oleg Cassini mingled with Al’s law partners, Governor George and Libby Pataki, and State Senate leader Joe and Barbara Bruno. Pols got a hit of the larger culture while everyone else made frisson-inducing small talk to power.

To most outsiders, it seemed exciting to be Al and Jeanine Pirro. Few, though, knew much about the speed bump along the route. At 39, Al was admitted to Fair Oaks Hospital in Summit, New Jersey. He was depressed, couldn’t sleep. He cried spontaneously and contemplated suicide, according to the hospital report. Partly, the crisis was brought on by the lieutenant-governor debacle. Al, as Jeanine knew, was obsessed with being a success. That Al, a rising business and political power, had proved a liability to his wife devastated him. Twenty years later he tells me, “There was a deep hollow feeling in me. Not just humiliation, a loss of my self-esteem.”

Other factors clouded Al’s mental health. Like his affairs. One in 1983 had produced a child. There’d been other one-night stands, and a liaison with a lawyer in his office. Jeanine, when she learned of his infidelities, slapped Al and threw him out. Still, when she considered Al’s misbehavior, she thought about his complicated drives, his frustrations. She found cause to blame herself, at least a little, even for the affairs. She knew that Al, whatever his public pronouncements, was deeply ambivalent about the career she so feverishly pursued. “Al took no pleasure in [my] fame,” she told one of Al’s psychiatrists.

Al sometimes said he didn’t really care about money. Jeanine, though, loved their lifestyle, which she certainly couldn’t afford on a public servant’s salary. Al picked up the tab. (Al, she noted, was the type to foot the restaurant bill even if now 30 people were at dinner.) Al’s mental-health problems had caused some financial losses; Jeanine couldn’t help but be angry about that, too. She put financial pressure on him, as she told the psychiatrist.

And, she acknowledged to the psychiatrist, she was “quite domineering,” which probably upset Al. As her friends knew, Jeanine didn’t mince words. “She could peel paper off the wall,” said one, referring to her foul language.

Jeanine seemed to feel for Al; maybe dealing with someone like her wasn’t easy. Perhaps that’s why she took him back. She was furious, but she made it clear to the therapists that she was committed to the marriage. Al let the doctor know he fervently wanted to undo the damage to the relationship with Jeanine. He longed “to be understood, to be taken care of,” the report said. “Al states that his greatest fear is that his wife will leave him,” says the psychiatric report.

After two months in the hospital, Al emerged with the depression lifted and with renewed, seemingly redoubled energy. He set about rebuilding his business, becoming his law firm’s rainmaker. He threw himself into the social whirl of Pirroland, the gatherings and the elaborate dinners. The table was magnificent. There were gold napkin holders. Ruby-red goblets. And room for more than twenty. They employed help, but Jeanine did a lot of the cooking. “I love to cook,” says Jeanine. Al liked to putter around the kitchen as well. (“Al’s not as good a cook,” says Jeanine, “and he’s a mess in the kitchen.”) Mostly, the kitchen was Jeanine’s spot. (If they were in there together, there’d be trouble. “We’d kill each other,” she says.) Jeanine liked to prepare Lebanese meatballs—she’s Lebanese—while chatting with the girls (the county executive’s wife or Barbara Bruno). They gabbed about politics or bikini waxing. “She’s really good to her girlfriends,” says a friend.

For some of Jeanine’s supporters, mixing the D.A.’s world with Al’s was unsettling. Al was a person to be leery of. “He was unpredictable,” says one longtime former staffer. “In a quest for attention or escape or whatever his motives, he always ends up in the newspaper.” Still, one guest recalls how charming and sweet Al could be, especially to Jeanine. Al was the funny one; Jeanine the straight man. In a party setting, he was proud and teasing; he flirted with her. Though, of course, the flirting could be barbed.

“Let me tell you what happened to me today … ” Jeanine might begin.

“Oh, yeah, everybody wants to know all about Jeanine,” Al would joke.

To most observers, the marriage seemed back on track. Jeanine hadn’t missed a beat—she coped by burying herself in work. She was the crusading D.A., loved by (and in love with) the cameras; Al was the political muscle and moneymaker. It was Al who brought the governor into their midst. Al had supported Pataki when he was still a state senator from nearby Peekskill. Al opened a lobbying firm in Albany, which by Pataki’s second term brought in more than $500,000 a year in revenue. Libby Pataki and Jeanine also became fast friends.

It was a merry mix, and at the end of a festive meal shots of tequila were sometimes set up. (Once, a potbellied pig wandered under the table.) Everyone was thrilled to see the governor throw one back before hitting the road. It was a perfect Pirro moment, downmarket fun in pricey company.

Then, in 1998, a few days before Christmas, the subpoenas began arriving. The investigation had started over a $5,000 check Al wrote to a Yonkers politician. The politician later claimed it was a bribe. Al said it was a consulting fee. Soon, the investigative focus had shifted. Al, the government charged, had understated his and Jeanine’s personal income by $1.2 million over eight years and, in the process, evaded $400,000 in personal income tax.

Al assumed the government’s true intent was political vengeance, an attempt to darken Jeanine’s political star. (Jeanine’s critics accuse her of a similar game. “If you oppose her on an issue, she’s vengeful,” says one Democratic county official.) Al had long seen the world as hostile, “a cold and threatening place unresponsive to his needs,” as the psychiatric report had put it a decade earlier. For Al, this investigation was further proof. Al believed politics was the reason he’d been investigated for the better part of a decade—by the IRS, the New York State Organized Crime Task Force, and then the U.S. Attorney, which, his lawyers calculated, issued 210 grand-jury subpoenas to everyone from his clients to his alma mater.

Of course, Al and Jeanine’s tax forms (they co-signed the returns) were fraudulent. Al’s businesses—he had 32 single-purpose entities, one for each real-estate deal—took about $20 million in deductions. The government alleged that about 5 percent of those really were personal. Some of the personal expenses charged to businesses were tantalizing. There was an anniversary stay at the Plaza, $1,800 grillwork for the pet pigs’ pen, a $4,450 portrait of their two children, Al’s $123,000 Ferrari 348 Spider convertible, even $70,000 to fight Al’s paternity suit. (Al claimed he had to fight. The mother is a convicted embezzler who’d listed another father on the birth certificate.) The government also discovered a complicated lease structure that allowed Jeanine to claim a Mercedes as hers, though one of Al’s companies paid for it. (One of Al’s companies also picked up the tab for Jeanine’s mother’s Mercedes, which pissed off his own mother.)

The indictment of the sitting D.A.’s husband was extremely embarrassing to Jeanine. That she had co-signed fraudulent personal tax returns was worse. She wasn’t, as critics pointed out, a naïve homemaker. How could she have known nothing?

Al admitted errors on his returns, but blamed sloppy accounting. He pointed a finger at his younger brother, Anthony, his accountant and co-defendant. Al may have written the checks or charged expenses to his American Express card. Anthony should have picked them up and reconciled them at year’s end.

“So that’s why I speed, so I can catch her attention?” Al asks derisively. “The more clever question would be, Do you feel you’re acting out some inferiority because your wife is more accomplished than you?”

One day, Al, fearing his brother was going to turn state’s evidence, invited Anthony to his office, and secretly videotaped the meeting. It’s a disturbing spectacle, the older, dominant brother pushing the younger brother to “tell the truth” and save Al’s skin. On tape, Anthony admits he was negligent, careless. To Anthony’s mind, the problem was that if he tried to ask questions, he tells Al, “you scream at me.” The only time they met was when Al and Jeanine signed the returns. (Then Anthony tells Al on the tape, “You sit there with Jeanine, banging your chest, claiming, ‘I made more than you.’ ”)

Anthony, a struggling middle-class accountant who couldn’t afford his own defense, had been in therapy for years, and one of his issues was how to stand up to his older, successful brother, also his most important client. On the tape, Anthony, in what seems like a therapeutic breakthrough, tells his brother, “It’s me against you, Al.”

Al did everything he could to avoid indictment. He filed amended returns and paid nearly $1 million in back taxes and penalties. The government used the new returns as a road map to its prosecution. Its contention was that all those mistakes in Al’s favor couldn’t have been by chance. One year, Al claimed to have earned $620,000; later, the amended returns pushed it past $1 million. Either way, it wasn’t a lot for a place like Harrison. “You can’t live like a lord of the manor on that income,” pointed out a lawyer involved in the defense. “He needed a little tax help.”

Jeanine, in her second term as district attorney, appeared in court for most of Al’s trial. She and Al held hands, worked the press like it was a cocktail party. When Al was convicted, Jeanine, who prided herself on toughness toward criminals, wrote the judge a seven-page letter asking for leniency. “The mission ingrained in Al was to succeed and then give back to his parents and siblings,” she wrote. “He was indoctrinated to this by a variety of means, including physical violence and guilt.” The beneficiaries of Al’s giving back, of course, included Jeanine and the kids.

Al was sentenced to 29 months—he served eleven in prison. (Anthony received a stiffer sentence of 37 months. The brothers no longer speak.)

On the eve of prison, Al’s career, his pride, were in tatters. He seemed to give up hope for his marriage, the thing he’d once desperately wanted to preserve. “If this woman intends to pursue her career and continues to pursue politics, she should definitely get rid of me,” Al says. “I mean, that’s so obvious.”

Jeanine didn’t consider leaving politics. “For me, this is who I am,” she tells me. Jeanine forged ahead, winning again for district attorney. “My husband was in prison when I ran to be the chief law-enforcement officer,” she points out.

She did, though, contemplate leaving her marriage. Their political partnership was, by then, mostly over. Al may have created her, but she no longer needed his fund-raising talents. “She can raise money on her own now,” he agrees. “She stopped taking political advice from me.”

Al’s power base had been eroding anyway. Republicans no longer held sway in Westchester. The county had elected a Democrat as its executive. “It was made real clear to Al that there are new rules,” explains one Democratic leader.

Jeanine and their two kids visited Al in federal prison in Florida, where they have a second home. “The most difficult day in my life, other than the day when I watched my dad die, was when I took my children to federal prison to visit their father,” Jeanine says.

It was troubling for Al, too—he couldn’t seem to find much to talk about with his family after the initial greeting.

Jeanine decided she couldn’t leave Al while he was in prison, though some in her camp thought she’d be better off without him. “Things had changed in their relationship,” says a close friend in whom Jeanine confided after Al left prison. “She said, ‘I was with him through the paternity through the trial through prison. If I had every reason to leave him those times, and certainly I did, what reason is left to me now?’ ” To the friend, it seemed that Jeanine had tested the limits of till-death-do-us-part. “At some juncture, you’re no longer at that point at which things are going to break. You have that thing that’s called a family. That’s how she explained it to me,” the friend says.

And yet her decision seemed, publicly at least, like a compromise, and not a happy one. She had trouble affirming her love for Al. This past summer, she told the Post that she loved her family. She pointedly avoided saying she loved her husband, even when asked directly. Perhaps it was the astute political move to distance herself from Al. Still, one colleague recalls that it was about then that she again wondered about divorcing Al, maybe when the campaign is through.

Whatever the motive, Jeanine’s careful parsing of the love question disturbed Al. “You’re reading in the paper that your spouse was asked whether she loves you or not, and she says, ‘I love my family.’ How would you feel?” Al asks me.

“Shitty,” I say.

“Yeah, I mean, certainly it’s hurtful.”

“What do you say to her about that?”

“Nothing,” he says.

For Al, it’s a depressing turn. “I’m sure that in some measure she blames me,” Al says. “I think we blame each other.”

“What would you say if I asked if you loved her?” I ask.

Al pauses for a few seconds. “I would say that’s my personal business.”

Al’s attorney, whose office is across the hall, shoves open the door to Al’s office. “Is everything all right?” he asks. “It’s been two fucking hours.”

Al’s back is to the door. He barely turns. “We’re good,” he says quietly. His lawyer departs.

These days, Al is trying to cope, trying to walk into meetings as if the newspapers on every client’s desk don’t shout his name. Once he’d described himself as a “power broker” and “a friend of the governor.” Now he’s retrenching. He’s shutting down his lobbying business at the end of the year. Al says the business never really recovered from the tax conviction. “Lobbyists carry juice. They provide access. They fix things. Does a convicted felon still fix things?” he asks. Even Al’s traditional route to power, his ability to raise money, has been compromised. “Do the politicians want to accept a check from a convicted felon?” he wonders.

Al admires Jeanine. “She’s extremely bright, articulate, very personable,” he says. And yet he seems to want another type of wife. Al isn’t getting a lot of understanding at home.

“Anytime you have two professionals who are similar in personality in that they are type A, there are voids, and one of the places that does occur is in the home,” Al tells me. “So yes, it is difficult in that it is a constant challenge to keep communication going.” Lately, the wife of a lawyer who defended Al at his tax trial, a family friend for years, has been named in the tabloids as “the other woman.” Lisa Santangelo is 35 and attractive, with long dark hair, like Jeanine used to have.

Al denies that they are having an affair. “You guys are just friends?” I ask.

“Best of friends,” he says. “There is no sexual relationship.”

“So you don’t cheat,” I say.

Al pauses. “What do you mean by ‘Do you cheat’? You talking about going out? Or you talking about sexually?”

“Sexually.”

“No. No. No. There’s no harm in having a female friend. I think there’s a difference between being charming and holding yourself out as being available.”

“You don’t do the latter?”

“I don’t think I do,” he says, “but if that’s what people say, you know, who am I to say? I don’t see myself that way.” Al says he wants other things from female companionship. “You need to have someone tell you that you’re smart or you’re good-looking or you made a good business decision,” he says. “I think Jeanine needs that. I need that. Everyone needs that.” Al’s not getting that at home. “Do I think that I would like to have more attention at home?” he asks. “Yeah. And, you know, if you’re not going to get attention at home, I think you really need to make some decisions about your future.”

And yet, even if Al isn’t cheating, his behavior is provocative, especially with a wife running for attorney general. Speeding may be unintentional—“You’re not paying a lot of attention to the speed limit,” says Al—but spending time with Santangelo has been intentional. They’ve been alone on Al’s boat. They’ve been seen together at the Westchester Country Club. Clearly, Jeanine was provoked. In the summer of 2005, she had Al followed. She spoke with Bernie Kerik, the former New York City police commissioner and onetime nominee to head Homeland Security who was, at the time, embroiled in his own professional and personal scandals. “Bernie’s a friend,” Jeanine says by way of justification. She urged Kerik to bug her husband’s boat. That conversation was recorded by federal investigators examining Kerik. Now the government is said to be investigating Jeanine. Portions of Jeanine’s conversations with Kerik were leaked to WNBC, a leak targeted for maximum political damage.

In transcripts, Jeanine is at her wallpaper-peeling best. “What am I supposed to do, Bernie? Watch him fuck her every night? What am I supposed to do? I can go on the boat. I’ll put the fucking thing”—the bug—“on myself,” she tells Kerik. Al says he learned about this, like everyone else, from the media.

As it stands now, Al will likely get his wish. Jeanine’s political career will soon come to an end. There is a chance, of course, that the publicity could serve Jeanine. She would not be the first female politician whose husband’s escapades led to gains in the polls. Still, if Jeanine does exit politics, it’s not clear to Al that that alone will make things right at home.

“That’s something that I don’t know,” says Al. “At some point in time you sit down and you discuss what you want to be and what you want to do.”

“You’re against divorce,” I say.

“I’m not saying that,” says Al.

In Jeanine Pirro’s campaign headquarters, there’s a wall of articles chronicling her accomplishments and showing her in attractive poses, often featuring her legs, with an angular face. In person, she is softer, her features wrinkle-free but not sharp. She wears a smart yellow businesslike suit, one of half a dozen Armanis. Jeanine, I know by now, isn’t bland and disciplined; she’s not Hillary. She is, though, a practiced politician. And so she nods to my question, then answers another. I ask about what she calls the “smear campaign” against her, and she segues to her fighting spirit, which leads to her fight for women. “Whether I was the first woman to prosecute a murder case, first woman judge, first woman D.A., I always knew that women would benefit if I did well and would be hurt if I didn’t,” she tells me, as she’s told a thousand others. And so, in an attempt to steer her into something less rehearsed, I say, “You know I spoke to Al.”

Jeanine becomes alert, and quiet. She wants to know what Al said. It seems odd, of course, that she doesn’t know. But, then, Jeanine is accustomed to Al’s independent streak, even charmed by it. Indeed, thoughts of Al being Al seem to tickle her. He might be naughty, but he’s interesting. “Not a surprise that he didn’t ask my opinion,” she says with a smile. “I think Al needs to speak up for himself.”

Al believes her career has been hard on him, I tell her.

“No question,” she says. “We have persevered through some very difficult times. It’s been hard on both of us and hard on our careers.” She knows that Al wants her out of politics. “For years, he’s wanted me to go on television,” she says. Jeanine considered it. Al says she had an offer of over $1 million a year. “I want to be the one doing, not the one reporting on people,” she says.

“Has Al made peace with that?”

“Maybe not,” she says with a laugh. She’s got a deep, rich, engaging voice, a genuine laugh. “Maybe not.”

“How’s your communication these days?

She chuckles again. “In need of a little repair, I’d say.”

They seemed so close during the toughest times. During the tax-fraud trial, they walked down the courthouse steps hand in hand.

“Do I think that I would like to have more attention at home?” he asks. “Yeah. And, you know, if you’re not going to get attention at home, I think you really need to make some decisions about your future.”

“I wasn’t going to turn my back on my family because people felt that I would look better politically,” she says. “That’s not how I was raised … The sense of the family is the most important thing for me at all costs. My family is my family.”

“Including Al?”

“Al is my family. We’re a unit, and I fought hard to keep my family together. Look,” she tells me, “he’s my husband and the father of my children.”

For Jeanine, this has been the divide. Al was the love of her life—“I was crazy about him,” she says when she talks about their time in law school. Now he’s the father of her much-adored children. It might hurt Al—she knows it hurts Al—but it seems the deal she’s made with herself. And given this, I wonder why she flipped out last summer. Why talk about bugging her husband?

“I wanted to know. I needed to know.”

So she called her old friend Bernie Kerik, though he was under investigation himself.

“Why did I call Bernie? I wanted honesty and I wanted to know,” she says. “And you know what? I was angry and I said things I shouldn’t have. But you can’t change what you did; you can only learn from it.”

“Do you think Al had an affair?”

“I don’t know. I suspected it.”

“What’s the difference?” I ask.

Jeanine, I know, exercises every morning and snacks on sweets all day. At the conference-room table, she gobbles dark chocolate.

“God almighty! What do you mean, What’s the difference? Because I wanted to know what I was dealing with. I wanted the truth. I’m the prosecutor. That’s who I am.”

“Would you have thrown him out?”

“I don’t know. I needed to know the truth.”

What wife doesn’t want to know if her husband is cheating? And yet this couple seems to have come to accept that their lives have diverged.

“Yes, the circumstances of our lives have caused us to move in different directions, but that core, my children, is still there.”

Didn’t they have a tacit understanding, she and Al? He’s great company, funny as hell, a partner in their shared strivers’ dream, but didn’t she expect to put up with a misdeed or two? Compromises are made, as married couples know. Didn’t she turn a blind eye to his frequent female dinner companions?

“See,” she says, “there wasn’t an understanding. If there were, why would I have cared?” And then, irresistibly, she slips into campaign talk. “I’ll tell you what, I’m a fighter. If I weren’t, I wouldn’t have started a domestic-violence unit, I wouldn’t have taken on the people I have taken on … ”

I interrupt. Is she relating that to the issue of bugging her husband?

“I’m backing into it,” she says. “I’m saying I’ve fought my whole life for what I believe in, and I was fighting for my family.”

“So you’re going to stay married? Going to keep the family together?

“Like everyone else, I’m working to keep it together. It’s not easy.”

“That is a good line. It’s also probably true,” I tell her.

“Can I tell you something? I’m not good saying things I don’t believe in.”

That seems like an invitation. “Do you love your husband?” I ask.

Jeanine has picked through the chocolates, taken those she wants.

“Of course I love my husband,” she says. “From the day that I met him.”

Additional reporting by Ariel Brewster.