‘I think it’s hard to ask women for their vote and at the same time not be an outspoken proponent for the things that matter to them,” Elizabeth Edwards is saying of Hillary Clinton as a twentysomething staffer drives her through the cornfields of Iowa. “My friends get telephone calls—it’s not like it’s something I’ve heard about—my friends get telephone calls where they’re asked, you know, ‘This is a woman, it’s really historic, women need to support women.’ All of which is fine.” Edwards sighs. “But given that she’s not as up front on these women issues,” by which Edwards means poverty and health care, which disproportionately affect women, “and then there are other sorts of odd issues that nobody pays any attention to: There’s women-in-the-armed-forces issues; she’s on the armed-forces committee, she could be speaking out about that, and she really hasn’t been. It’s like she wants to play both sides. And that’s my complaint.”

But then it was Hillary who enabled Edwards’s complaint. The fact that Elizabeth Edwards can so blithely be both a cookie-baker and a political commentator has everything to do with Hillary, who insisted on being judged by the same standards as a man, who refused to play a secondary role, who (often clumsily) forced herself into the public debate, even before she was running for office.

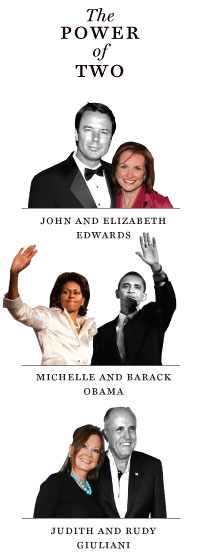

More than any other in American history, this election has upended our gender politics, and it’s not just because Hillary Clinton has a legitimate chance to be the first female president. She so vastly expanded the definition of what a political wife could be during her eight years in the White House that during the current campaign season, all the old scripts have been thrown out, and the couples are improvising—with sometimes painful results. It’s often seemed like politics as postfeminist comedy, what with Mitt Romney’s strapping his dog to the top of his car on a family trip—the ludicrousness of the old-school dad—and Rudy Giuliani’s taking a call from his wife in the midst of a speech to the NRA.

It’s never seemed more like we’re electing not only a president but a couple. With some exceptions, the current crop of would-be First Ladies is like some wet dream of Judy Chicago’s. (Laura Bush was a blip—a throwback to the days of Nancy Reagan, when First Ladies hid their power behind the mask of the Stepford Wife.) This time, almost all of them unapologetically play both the wife and the powerful consigliere (or in Elizabeth Edwards’s case, the political hit man). Michelle Obama went to Princeton and Harvard Law, met her husband when she was assigned to supervise him at a law firm where she outearned him. Jackie Clegg Dodd is on five corporate boards. Even the alleged bimbo of the group, Fred Thompson’s 24-years-younger blonde trophy wife, Jeri Kehn, isn’t exactly some dopey little cupcake—for one thing, she’s 41, and for another, she used to be a communications adviser for the RNC, a job even more challenging than the one Joe Scarborough imagined for her, as a gal who “works the pole.” Even if America doesn’t get a brilliant, powerful, penisless person in the Oval Office, it will very likely still get one in the White House. These First Lady aspirants prove what we all knew was coming: Après Hillary le déluge.

It’s not just the spouses who are different in this election (like Hillary was), it’s the marriages (like Hillary’s is). It seems surreal now, but in the last election, marriage—protecting it, defining it, feeling entitled to it—was almost as big an issue as Iraq. Hillary may not have been much of a presence in ’04, but the memory of her messed-up marriage was as much a motivation as homophobia for the obsessive focus on the state of our unions in that election. But we’re done with that now. The Bush presidency has been about denial—in so many ways—but you can only stay in denial for so long. The nontraditional, compromised, and representative nature of every marriage on display in this campaign season says that we’re ready to admit that the myth of sanctified, permanent, monogamous marriage is just that: a quaint fantasy. Look at the divorce rates; think about your friends; get a clue.

Barack Obama tells us that his marriage went through a period when “my wife’s anger toward me seemed barely contained.” (Ah, the simmering hostility of matrimony!) John McCain met his current wife, Cindy, while he was still married to his first wife, Carol, before Cindy developed an addiction to painkillers and they adopted a baby from Bangladesh. Rudy Giuliani, of course, started taking Judith Nathan to Yankees games and parades while he was still married to his second wife, Donna Hanover, and had the class to inform the mother of his children that their marriage was over via a press conference. Fred Thompson is a senior citizen with a hot wife and toddlers (which just makes him seem more like the actor he is and less like the president he wants to be). The only truly apple-pie-ish marriage in the lot is Mitt and Ann Romney’s—and they’re Mormons.

Again, a lot of this has to do with the Clintons’ marriage, which, after all the drama and cigars, represents the slog of staying together—because of the children or because of ambition or because in some nagging, primal way you still need each other. There comes a point in many fraught but decades-old marriages when the terror of having to reconstruct an identity without the partner you’ve had weighing you down and propping you up since you were basically a kid is more awful than the prospect of spending another twenty years fighting it out. It’s a partnership, where gender roles (and, one guesses, sex) play a minor part. Maureen Dowd was perhaps the most prominent of the female critics to assert that Hillary Clinton’s failure to dump her husband after his philandering rendered her “unmasked as a counterfeit feminist.” But that’s wrong. It was more like she was unmasked as an ordinary woman: frustrated, disappointed, pragmatic.

It’s funny, though, how many different kinds of people are sure that Hillary Clinton’s stubborn refusal to get divorced is evidence not of family values but of renegade (feminist) cunning. “You and everyone you know probably despise Hillary Clinton,” John Podhoretz wrote in Can She Be Stopped? “You think she stayed in her marriage because she was hungry for unelected power, and that disgusts you.” The fear that women will get something they don’t deserve because of the man they have managed to seduce is incarnated in this election, of course, by the deliciously villainous Judith Giuliani. The Giuliani campaign has obviously noticed the shift in marital roles Hillary Clinton initiated, and has attempted a response. Hearing Rudy tell Barbara Walters that he’d be “very, very comfortable” with his wife sitting in on Cabinet meetings had uncanny echoes of that fateful 60 Minutes interview when Hillary naïvely told the viewing public, “I’m not sitting here as some little woman standing by my man like Tammy Wynette.”

But there’s an important difference. People may have recoiled from Bill Clinton’s ill-conceived two-for-the-price-of-one campaign pitch, but if they bothered to learn about the woman who was at that time named Hillary Rodham Clinton, they had to concede that she was eminently qualified to contribute to his administration. Judith Giuliani, by contrast, is at an absolute remove from presidential timber. (Her justification for claiming “expertise” on how to handle chemical and biological disaster is based mostly on a year of nursing and possibly some experience stapling dogs’ gullets.) The Giulianis walked into a trap left by Hillary. She changed the expectations for a political wife, and now it’s a much more demanding role.

Edwards says she’s “completely sympathetic” to Clinton’s current struggle to be perceived as un-girlie. “She knows, as I know, that there are people out there who have trouble imagining a commander-in-chief that is a woman,” she says. “She has to convince them—wrongly, mind you—that despite the fact that she’s a woman, she has what it takes. Her job is much harder in that respect. But I do think that what it means is that we want some assurance that she’s not just a symbolic woman—that she’s really going to be a great voice for us. And in the campaign? This far? She hasn’t really done as much as I would’ve expected or hoped.”

But the main reason Elizabeth Edwards can say whatever she wants, can speak so freely, so knowledgeably, and so aggressively—and still seem so cozy—is that by actually running, Hillary Clinton is doing Edwards and all the other candidates’ wives the favor of absorbing much of the anxiety, suspicion, and contempt many Americans still feel toward accomplished women—which would otherwise be directed at them.

SEE ALSO:

Contemplating Clinton II