Christine Quinn is crying. This isn’t an ambiguous, Hillaryesque moistening. The speaker of the New York City Council is tearful: big-globs-of-water tearful, speech-strangling tearful, uncomfortable-to-watch tearful. Quinn is in the middle seat of a big black city-owned SUV, on her way to a long-scheduled appearance at the 92nd Street Y, part of a series about women in politics. But wherever the red-haired 41-year-old goes these days, the prime subject is the scandal enveloping the council. Millions of taxpayer dollars have been channeled through fictitious groups to organizations that barely function and to outfits that seem to exist primarily to enrich relatives or supporters of council members. The dubious spending began years before Quinn was elected speaker in 2006, but that hasn’t spared her from a daily battering. She’s gone from being a well-respected contender for the 2009 Democratic mayoral nomination to the tabloid poster girl for inept leadership and sleazy spending with dizzying speed. Today’s setback was the announcement by City Comptroller Bill Thompson, a rival of Quinn’s in the ’09 mayor’s race, that he’d made a deal with the mayor’s office to review all council budget awards, effectively cutting Quinn out of the process. Plus the Post continues to mock Quinn by repeatedly running a photo of her with her eyes closed, seemingly on the verge of passing out.

Yet what turns on Quinn’s waterworks isn’t the political firestorm she’s living through, at least not directly. I’ve asked how her 81-year-old father, Lawrence Quinn, is handling seeing his daughter take a public drubbing. Lawrence Quinn, a retired electrical engineer, is a fixture at his daughter’s events and a comic foil in her speeches. “Um …” she begins, then pauses as the tears start flowing. “I’m not supposed to cry,” she finally says haltingly, forcing a laugh. “It’s way too girlie.” She collects herself. “He, um—my last tissue!” Another pause. “He’s been great, in that Irish 81-year-old guy’s way: ‘Okay, Christine, we’re gonna get through this, we’re gonna be fine!’ ” Imitating his gruff voice only provokes more tears. “But you know I’d rather provide him great opportunities, make him proud—” Her voice cracks.

Minutes later, Quinn’s father comes up again (her mother died of cancer when Christine was 16). This time, though, the moment provides a window into a different side of her. She’s perched in a tiny chair in the 92nd Street Y’s children’s library, chatting with some of the Y’s executives while waiting to go onstage for a Q-and-A with journalist Meryl Gordon. The conversation meanders from the early returns in today’s Pennsylvania presidential primary (Quinn’s a strong HRC backer) to obscure Bruce Springsteen B-sides (Quinn’s a huge fan) and is a reminder of Quinn’s gifts as a person and a politician: She’s funny, self-deprecating, knowledgeable on a wide range of subjects, an engaging storyteller. On the table is a children’s book titled Jacob’s Ladder, which prompts a discussion of the Tim Robbins movie of the same name and the biblical Jacob. Quinn mentions that she turns to her dad whenever there’s a question on Roman Catholic arcana; recently he dissected the confusion of Maundy Tuesday with Maundy Thursday. “But the day in-between is the interesting one,” Quinn says, her eyes narrowing. “The Irish call it ‘Spy Wednesday.’ That’s the day Judas betrayed Jesus. And the Irish are always most concerned about who’s screwing who politically.”

There are plenty of venal, egomaniacal, and downright corrupt politicians in the world, and even a few right here in New York. Christine Quinn is something more complicated and more compelling. She emerged from Manhattan’s left-wing, good-government tradition but has the hard-boiled soul of a Hell’s Kitchen ward boss. This is, possibly, a terrific combination in a modern public official. Throw in the fact that Quinn is proudly gay, and female, and her rise becomes not just politically intriguing but culturally symbolic. Yet now Quinn finds herself in the middle of a potentially career-ending crisis in large part because of the contradictions she’s embraced: positioning herself as a reformer of big-money, insider politics while playing the old-school game of favors and punishments.

Which doesn’t make her a hypocrite, exactly. It just means that as Quinn tries to navigate the City Council’s slush-fund scandal—which has already rung up the arrest of two council staffers and includes expanding investigations by both federal and local law-enforcement officials—she has an extraordinarily difficult juggling act to perform. The city’s newspapers are gleefully taking daily turns chasing down corrupt council spending. That would be plenty for any speaker to contend with, but Quinn’s first reactions to the scandal made matters worse: Her abrupt proposal to turn over most of the council’s budget power to the mayor set off howls in the ranks of members. So Quinn pivoted, made a show of apologizing to the council, and dropped her plan.

Quinn has risen this far on her keen political instincts. Now she’s trying to steer between the demands of 50 council members and the interests, often conflicting, of the city at large—and of the hundreds of thousands of voters she’d need to be elected mayor. Making nice with the council short-term doesn’t change the fact that Quinn’s best hope for remaining a mayoral contender lies in distancing herself from the very legislative body she leads. It’s a delicate, maybe impossible balancing act. Enough to make anyone weep.

It’s common to divide the City Council’s members into delegations by borough. The real organizing dynamic, though, is class. There are three main groups: The smallest is made up of the younger, wonky, exhaustingly ambitious types, many of whom were congressional or council staffers and can envision themselves as the next Chuck Schumer; people like Brooklyn’s David Yassky, Queens’s Eric Gioia and John Liu, and the Upper East Side’s Jessica Lappin. Another faction comprises the council members who’ve inherited the job, either literally or through time in a neighborhood political machine—such as Inez Dickens of Manhattan, Al Vann of Brooklyn, Peter Vallone Jr. of Queens, Joel Rivera of the Bronx. (A subset is formed by the type of sharp-elbowed operator whose council seat is often the hub of a local fiefdom, like Larry Seabrook of the Bronx, and who will probably head a community group supported by council funds when they leave office.) The third group is the government nerds. Its members started as activists, ran for the school board, moved up to a community board. They have a quaintly earnest devotion to democracy and no illusions that they’re going anywhere more prestigious—maybe a seat in the State Legislature. Here you find David Weprin of Queens, Lew Fidler and Tish James of Brooklyn, Gale Brewer of Manhattan.

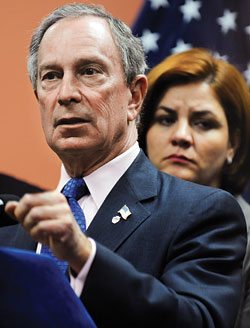

What unites council members is a distinct inferiority complex. The city’s charter gives the mayor the vast majority of practical power over city functions. That’s why internal council fights over, say, the renaming of a street become so ludicrously intense. The sense of second-class citizenship has deepened considerably during Michael Bloomberg’s six years in office. The mayor’s side of City Hall is full of mammoth flat-screen TV’s; the council side is held together with duct tape. And Bloomberg’s lack of allegiance to any party may have been good for the city, but it’s as alien to council members as his eleven-digit bank balance. Quinn, many members believe, has cozied up to the popular Bloomberg in service of her mayoral ambitions—and at the council’s expense.

“Did I think, as a speaker, having the [reserve] money to give out through the year might give me political leverage? Of course I did. I’m not going to lie to people that I didn’t think that.”

All of which is why the rebellion against Quinn has been so fierce. It isn’t so much differences over budget policy as Quinn’s betrayal of the culture of the council. She was one of them, after all. Quinn got into politics in 1991 as a staffer for Councilman Tom Duane. When Duane was elected to the State Legislature, Quinn won the contest to replace him. She’s always reveled in the minutiae of zoning bills and council procedure, and she became well liked across the ideological spectrum by being an open-minded team player. “We’ve known each other since 1992, when we were both staff,” says Jim Oddo, one of the council’s two Republicans. “I consider myself a close friend of Christine’s. She’s the smartest person in the room. I don’t mean that in an Al Gore way; she’s the most prepped, the most organized person. She immerses herself in details.”

That reputation has made it difficult for people who know Quinn well to believe she was in the dark until last year on the extent of hidden council cash. “I had heard the term holding codes the summer or so before I got elected speaker,” she says. “I had no idea what it was.” As a rank-and-file member, had she ever received money outside the standard budgeting process? “Sure,” Quinn says. “I can’t recall going in to say, ‘Here’s X group that needs Y.’ I do remember getting calls, ‘Oh, hey, here’s $10,000 if you need it for a senior group.’ As a member, you don’t particularly think about where that comes from.”

When Quinn campaigned to replace Gifford Miller as speaker two years ago, her willingness to cut deals for votes brought Quinn the crucial support of the Queens and Bronx Democratic leaders and signaled a change in style that eventually alienated many members. “She was a very different person when she was running for speaker,” one council member says. “She needed people then. Now she’s become this hard-ass: slights, perceived slights—it’s iron fist all the time with Christine.” Quinn’s temper, expressed in a sharp, nasal accent that’s a combination of Edith and Archie Bunker, didn’t help. She has pushed through bills making it harder for lobbyists to influence public officials and tightening campaign-finance regulations. While many council members agree with her changes, even more chafe at what they think is the inference behind Quinn’s agenda—that she’s the white knight cleaning up the council cesspool.

The council’s current money scandal is actually two scandals. The first part involves “member items,” the annual disbursement of tax dollars to community groups according to requests from individual council members. The dispensing of member items has long been one of the council speaker’s greatest powers. Quinn, to her credit, took steps to make the process more visible, instituting a paper trail for each item. Members, for the first time, are also supposed to declare possible conflicts of interest. Still, cash has found its way into strange pockets. Maria del Carmen Arroyo of the Bronx steered $82,500 to a social-service agency that had employed her sister and a nephew. Seabrook applied for nearly a million bucks for the Bronx African American Chamber of Commerce, an operation that happens to share an address with Seabrook’s district office. Last month, U.S. Attorney Michael Garcia indicted and arrested two staffers of Brooklyn councilman Kendall Stewart for siphoning $145,000 of member-item money from a charity: the Donna Reid Memorial Education Fund.

The second source of trouble has roots extending to at least 1988. That’s when the council began setting aside fairly small amounts of budget cash for a reserve fund, to be used throughout the fiscal year to correct errors or respond to emergencies. The reserve fund may have plugged legitimate holes, but as it grew, particularly during the term of speaker Gifford Miller, it provided the speaker’s office a powerful sub rosa tool to reward friends.

The practice of using fictitious groups to park money for later distribution dates as far back as fiscal year 2001, under speaker Peter Vallone. In fiscal year 2007, eighteen nonexistent groups with borderline-comical names such as “Coalition of Informed Individuals” were funnels for $4.5 million. Quinn was moving to eliminate the reserve funds—and says that when she first learned of the bogus groups, about six months ago, she immediately forwarded the information to federal and city investigators.

One week after the Post broke the slush-fund story, Quinn, trying to appear aggressive, called a press conference to unilaterally announce her budget-reform proposal. The key idea was shifting control over discretionary spending to the mayor’s office. “When you jump out there and suggest the power be given to the mayor, it’s an implication we’re not doing the right thing,” council member Fidler says. “This notion that we’re all pigs at a trough is offensive. We’re part of the budget process—by charter. It’s one of the few powers we’ve got!”

Certainly part of the council’s rebellion is about its diminishing power. But the fact is that in many districts council members are the public’s only real contact with elective government, and for smaller groups, member-item funding is a dire necessity. While a few corrupt, self-dealing members deserve legal jeopardy, most are an important link to the nuts-and-bolts functioning of the city’s myriad neighborhoods. “It’s not like we’re building a bridge to nowhere in Alaska,” Fidler says. “These member items that get called pork are the lifeblood of 200 to 300 not-for-profit organizations that do valuable work. We should be telling people clearly what these groups do: ‘This is a homeless shelter, this is an aids-prevention program. It may have a strange name, but this is after-school-program money.’ ”

There’s another factor fueling the anger at Quinn, though. “Her press conference was totally and utterly disingenuous,” Liu says. “It was held not by a speaker but by a mayoral candidate. Someone who should have been functioning as the leader of the legislative body threw us under the bus.” Liu readily admits that he’s considering running for comptroller next year. He’s hardly alone: Thanks to term limits, nearly half the council is angling for some other job. If Quinn doesn’t stick up for the council’s image, it hurts their chances.

The slush crisis appeared at the high point of Quinn’s speakership. She had spent months talking up the environmental and health benefits of congestion pricing. Then, as the deadline for federal funding loomed and Bloomberg pressed for legislative approval, Quinn was at her inside-politics best: cajoling, threatening, and stroking council members. On Monday, March 31, she assembled a solid 30-20 majority vote in favor of the controversial plan to charge drivers $8 to enter midtown Manhattan. Perhaps most impressive, Quinn found twenty of the votes in members representing outer-borough districts, where supporting congestion pricing was a real political risk. “She knows when to use sweetness and when to apply pressure,” says an aide to another city official who watched Quinn closely during the congestion-pricing drama. “I was incredibly impressed. She proved herself an extraordinarily capable politician. That’s the irony of what came next.”

The Post broke the slush-fund story three days after Quinn’s triumph. Her slide downhill accelerated the next week, when state assembly boss Sheldon Silver refused to schedule a vote on congestion pricing. “As a leader Chris is the opposite of Shelly,” says a veteran political consultant who knows and likes Quinn. “On congestion pricing, he didn’t want his members’ names in the paper. He protected them. Quinn took the Times’s praise over exposing her membership.”

Council members were incensed, accusing Bloomberg and Quinn of lying to them. Quinn claims not to understand what went wrong in Albany. But that was the least of her problems: The slush-fund scandal was producing daily stories about hidden council funds doled out to flimsy, politically connected organizations. At a press conference the day of the first Post story, Quinn answered questions for nearly an hour, trying to confront every allegation. That night, at home with partner Kim Catullo, a corporate lawyer, Quinn says she couldn’t sleep. “I ran the story over and over in my head: What’s this going to mean? Will I be able to do this? Will I be able to do that? And it was making me sick.”

Three weeks later, sitting in her City Council office, opposite an enormous Lee Krasner painting, Quinn seems to have regained her equilibrium. Yet as soon as the conversation turns to her response to the scandal, Quinn begins tugging at the heart-shaped pendant around her neck. “At some point I had to make a conscious decision to put [the idea of running for mayor] on the shelf. Not in some wildly altruistic, ‘I’m better than other people who are politically ambitious’ way—but because it was making me crazy. If I asked one more person, ‘What do you think? Do you think I’ll be able to run for another office some day?’ Either people said yes, and I said, ‘Oh, you’re full of it, you’re just lying to me, you want to make me feel better,’ or they said no, and I’d be crushed and want to pull the covers over my head. So there was no point in the exercise. So I decided to put it aside. Tommy!”

She leaps up and dashes across the room toward an aide. Quinn has been sitting on her BlackBerry; it just buzzed with a message about a pregnant staffer, and Quinn wants to make sure the woman is safely on the way to a doctor.

These days, Quinn says, she’s concentrating solely on her job as speaker. “We need to pass a budget that New Yorkers can have some faith in, in the next eight to nine weeks. At a point like this, I can’t even begin to hypothesize what my political future might be. I don’t know. That’s really the furthest thing from my mind at this moment in time.”

Yet she’s going full speed ahead with a major fund-raising reception during Gay Pride Week in June. The invitation to the affair is refreshingly direct: “This event is to raise funds for Christine’s prospective run for citywide office such as Mayor in 2009.” Quinn has shown some early strength in the race to succeed Bloomberg. She’s raised a respectable $2.4 million, and coming from Manhattan gives her a broad and populous base. She wouldn’t have gone into 2009 as the front-runner—Congressman Anthony Weiner, by virtue of a strong 2005 primary run, has to be considered the early favorite—but the pre-scandal Quinn would have been a formidable contender.

“Someone who should have been functioning as the leader of the legislative body threw us under the bus,” says council member John Liu of Queens.

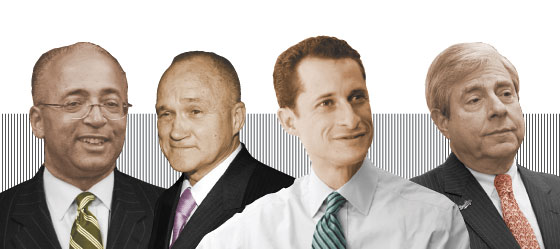

If Quinn is weakened or sidelined, Manhattan is in play. Weiner will get a greater hearing from yuppie voters. Bill Thompson, who’s raised the most money of the presumed contenders, will go harder after white voters. Tony Avella, a councilman from Queens, will argue that the scandal has proved his populist attacks on the culture of insider dealing were right all along. An even larger repercussion will be to enlarge the field. Marty Markowitz has been president of the city’s most populous borough, Brooklyn, for six years. Ray Kelly has presided over record-low crime statistics and come through the Sean Bell trial without a major racial eruption.

Bloomberg, who certainly owed Quinn after the congestion-pricing debacle, threw her an important life preserver by calling the speaker “the most honest person I know.” And last week, Quinn’s prospects got a badly needed boost from a Quinnipiac University poll suggesting a large majority of voters don’t blame her for the council’s shady reserve fund—though a worrisome 52 percent think she knew about it all along. “Her most serious problem is not allowing the idea that she can’t win because of the council scandal to set in and become conventional wisdom,” says a political strategist who has run mayoral races. “Not with voters—with labor leaders, the real-estate community, the chattering classes.”

All of the city’s editorial pages have called for a ban on member items. Quinn, scrambling to recover, had no chance of getting that through the council, and says she’s not even sure if it would be good policy. “It’s an idea and a suggestion I totally, totally understand. I understand where it’s coming from,” Quinn says. “The truth is, there’s a lot of politics in member items. There’s also some historical need for them. We, in a good way, are getting along with Bloomberg and trying to fund joint priorities. But there was a time when, if Rudy Giuliani didn’t like a group, the money didn’t go to them, whether it was in the budget or not.” Even if member items are sometimes a necessary corrective, does she think her first, tougher proposal would have been helped by discussing it in advance with council members? “In hindsight, I absolutely wish I had done more consultation,” Quinn says slowly. “Where myself and my colleagues end up at the end of this process will give illumination to where people would have ended up if there were greater consultation.”

Which is a roundabout way of saying “No.” So last week Quinn announced a compromise, reached after lengthy negotiations with council members: Instead of stripping the council of discretionary spending power, as she’d originally proposed, Quinn is backing a reform package that includes online disclosure of member-item requests and a more stringent review procedure for prospective recipients.

Quinn’s new plan falls short of what the papers have demanded. She’s assiduously courted the Times in particular; its endorsement carries great weight in a Democratic primary. One week after the slush-fund scandal broke, Quinn headed to the Times’ office to explain herself to members of its editorial board (Quinn says she’s had phone chats with editorial writers at the Daily News and the Post). So far, the Times has decried the council’s spending excesses and called on Quinn to fix the system. “The Times is buying the Quinn spin: She’s been trying to wrap her arms around this recalcitrant council to clean it up,” one member says. “There’s grains of truth in that. But the reality is that she was enormously power-hungry and was a control freak. I don’t believe she wanted the $4.5 million reserve for any personal enrichment. She wanted it for total control.”

Yet if Quinn is guilty of nothing more than playing hardball—and a panicky, self-interested initial response to the slush-fund scandal—she deserves a second chance. Some of the recent pounding she’s taken has been unfair; her predecessors Miller and Vallone should be sharing the heat. Certainly some of Quinn’s explanations have been dodgy. But she’s also capable of admitting, “Did I think, as a speaker, having the [reserve] money to give out through the year might give me political leverage? Of course I did. I’m not going to lie to people that I didn’t think that. Is that a good reform thing to have thought? No … But that’s the truth.” Quinn’s consultants are counting on short attention spans and the drying up of the council’s scandals to salvage her career. But more of that kind of bluntness would do her the most good.

Lately, Quinn has put away the tissues, vigorously defended her honesty, and focused on ways to minimize the pain from Bloomberg’s budget cuts. Yet clouds hover. Quinn claims two former budget staffers didn’t follow her orders to shut down the shadowy reserve fund; investigators will no doubt want to hear whether the ex-staffers’ versions are as complimentary to Quinn. The U.S. Attorney’s office and the city’s Department of Investigation are reportedly sifting through thousands of documents, concentrating on the financial records of 100 youth groups that received member-item funding. Quinn is tormented by the idea that more surprises may lie ahead. “Not having control over any situation for anybody is a terrifying thing,” she says, pulling fiercely at her necklace again. “If you’re somebody who likes control, it’s even more terrifying.”