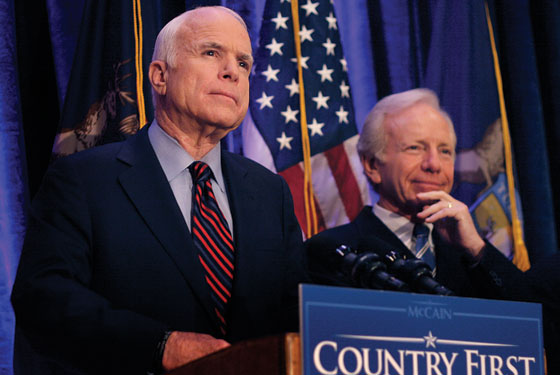

Senator Joe Lieberman enters the room, but I can’t see him—just a centipedelike scrum of black suits and Hasid hats that has formed around him and now moves, buzzing, toward the dais. We’re at a dinner being thrown at the Library of Congress by Agudath Israel of America, an assembly of ultra-Orthodox rabbis, and Lieberman is the star attraction. He’s come here to stump for John McCain, whose presidential endeavor the self-described independent Democrat improbably—make that unbelievably—endorsed last December. It’s mid-July now, and this is Lieberman’s fourth engagement of the day on his Republican friend’s behalf: He has spent the morning dispensing sound bites to CNN, Fox News, and MSNBC, from a nook festooned with McCain campaign logos. (“Have you taken a pad and pencil and figured out how many times Barack Obama has flip-flopped on Iraq?” soft-served the Fox host. “It’s a real serious question,” intoned Lieberman gravely.)

The adoring entourage finally falls away, allowing the senator, short and slight, to take his seat on the dais. His never-changing coif—a mass of yellowish-gray hair combed backward in two bulky wings—retains a whiff of seventies cool; it would go well with a turtleneck. Right now there’s a blue-and-white yarmulke nestled atop it. “I’m under oath today as a surrogate for John McCain, to speak to you about this great American,” the senator begins. The speech is a collection of familiar notes on McCain’s heroism, experience, and resolve. At some point, Lieberman says McCain will be “ready to lead on day one,” a phrase firmly associated with Hillary Clinton’s campaign. He also swipes a flourish from Obama’s post-partisanship playbook: “Too many people describe themselves as Democrats or Republicans, but forget that we’re all Americans.” Lieberman is just getting to what, in this room, is the red-meat portion of his remarks—the promise of a tough policy on Iran and total unity with Israel—when something makes him abruptly pause. Congressman Anthony Weiner, a Democrat from New York, walks in. For objectivity’s sake, the dinner’s organizers have invited him to campaign for Obama.

“Oh, hi, Congressman,” says Lieberman softly. Weiner smiles. For a moment, the senator looks ambushed, perhaps even panicky, as if caught in flagrante delicto by an ex. Officially, his relationship with the Democratic Party is supposed to be an amiable trial separation, not a nasty, soap-opera breakup. “Congressman Weiner,” Lieberman says, regaining his voice. “We debate, but we’re friends.”

Nothing in Joe Lieberman’s long and placid career—a respected attorney general in Connecticut, a centrist Democrat on the Senate floor, Al Gore’s high-minded running mate—could have presaged his current status: an apostate to his party and perhaps the most hated politician in the United States. Some days it seems like McCain himself doesn’t trigger as much vitriol from the left. The rancor between Lieberman and the Democratic-party elders has been amassing since at least 2006, when the senator “refused to crawl away and die,” in the words of a friend, after losing the Connecticut Democratic Senate primary to the upstart Ned Lamont and instead ran, and beat Lamont, as an independent. Some place the beginning of the end still further back, in 2004, when Lieberman’s pro-war presidential bid found no purchase with the party’s base, then at the apex of its anyone-but-Bush fury. There is no question, however, when the end of the end arrived: on December 17, 2007, when the senator, still caucusing with Democrats, threw his support in the 2008 presidential race to John McCain. Now, with his opening-night speech at the GOP convention approaching and Election Day just over two months away, Lieberman is poised to become a major spoiler for the Democrats, delivering votes in at least one critical swing state (he’s been trolling Florida for Jewish support) and bolstering McCain’s centrist appeal nationwide. In a year when Congress is all but certain to tip to the left no matter who wins the White House, Lieberman’s decision to abandon his party and back McCain is, depending on whom you ask, a bold stroke of political principle or a suicidal act of revenge.

Politicians’ office photo collections are usually displays of high-powered friendships and bi-partisan bonhomie. The most prominent photo in Lieberman’s lair in the Hart Building is one of the senator with Ronald Reagan, inscribed in the Gipper’s frilly handwriting; around it are snaps of George H. W. Bush, Bill Clinton, Chris Dodd from happier days, and, amusingly, Prince Charles. There’s only one small picture of Lieberman and John McCain, but the office itself is a souvenir of sorts. It used to belong to McCain.

Bi-partisanship, at least from the Democratic side of the aisle, isn’t what it used to be for Lieberman. Ever since he threw his lot in with McCain, the party Establishment, which had made peace with the senator’s “independent” tag, has turned its back on him. On the record, the Washington types still tread carefully for fear of jeopardizing Lieberman’s support; though he’s nominally an independent, Lieberman still effectively functions as the 51st Democrat in the Senate. “It’s more of a ‘What the hell are you doing?’ thing,” says Joe Trippi, a party insider and Howard Dean’s 2004 campaign manager. Off the record, however, his Democratic colleagues are fuming. The standard complaint goes something like this: Leaving the party was bad. Backing McCain is worse. And attacking Obama, as Lieberman has recently begun doing, is an unforgivable sin. “He has no allegiance to the party he was once a part of,” says a consultant to two former Democratic presidential candidates. “He says he’s an independent, but if you speak at the GOP convention, if you endorse McCain for president, you’re a Republican, end of story.” The political press has been even less restrained. Salon.com labeled Lieberman an “ideological turncoat.” “Watching Joe Lieberman go around the bend … is one of the strangest things I’ve ever seen in politics,” wrote Jonathan Chait in The New Republic. And Wonkette, the Washington gossip blog, turned the hatred of the senator into something like a literary extreme sport: “It’s like two quarter-pound stools of alien space shit crashed into a toxic-waste dumpster in Stamford, Connecticut, fucked, and out came their mutilated, blood-soaked carcass of a baby rat-child, Senator Joseph Lieberman.”

Lieberman still caucuses with Democrats on the Hill, but conducting Senate business has become a delicate dance. The Democratic caucus meets every Tuesday. “If they’re discussing civil rights, gun control, he’ll be there. If it’s politics, he’ll leave,” says a high-level Capitol Hill staffer. The exclusive, bi-partisan chairman’s lunch, where committee chairs mingle, is held every other Wednesday. The Democratic Policy Committee lunch is on Thursdays. Lieberman usually skips that one altogether.

There’s also tension within the senator’s staff. “He’s well liked, he’s a good boss,” observes a Senate insider. “But some of them started working for a Democrat … and ended up with this.” One staffer, Melissa Winter, Lieberman’s trusted executive assistant and scheduler for ten years, and a member of his and his wife Hadassa’s inner circle, quit to join the Obama campaign.

The relationship between Lieberman and Obama goes back to 2005, when Lieberman found himself a mentor to the incoming Illinois senator. “The mentorship program was set up to reduce partisanship in the Senate,” Lieberman says, chuckling at the irony. His first impression of Barack Obama? Lieberman takes a long, lip-chewing pause. “Someone very smart and very likable.” For a couple of years, the relationship between the two men was said to be collegial. It is now quite obviously fraying. In the summer, an incident made rounds in the press wherein Obama supposedly buttonholed Lieberman on the floor and loomed over him in an intimidating way. A leak from Obama’s campaign suggested that the candidate confronted Lieberman on his insufficiently forceful rejection of Obama-as-Muslim rumors. One insider has another guess—that the conversation had to do with Obama’s unrequited support of Lieberman in the 2006 Connecticut Senate race. “Obama, once you get beneath his patina of aloofness, is a real guy. He talks very directly in private conversation. I wouldn’t be surprised if that was a conversation about that—‘Hey, bro, what’s the deal?’ ”

Lieberman’s strange road from the Democratic ticket to rumors of a place on the Republican one goes straight through Iraq. After he emerged from the 2000 presidential campaign with a cache of national name recognition and Democratic goodwill, it was only natural that Al Gore’s former running mate would ponder a presidential campaign of his own in 2004. Early polling put Lieberman among the front-runners, but there was one problem: the war. In 2002, Lieberman had called George Bush’s case for the invasion “powerful” and “eloquent.” And despite the fact that the war was now wildly unpopular, its pretext debunked, and its handling demonstrably terrible, Lieberman was still unapologetically cheerleading for it as the 2004 race began. The hawkishness boxed him in. “It’s just amazing when you look at where he was and what he squandered,” says Trippi. “He was in a position to be formidable, to be the guy you needed to get by. Instead, he positioned himself in a completely nonviable way. He just made himself untenable as a Democrat.” The campaign never gained traction, and staffers’ claims of “Joementum” became an instant media joke. Annoyed party elders, coalescing around Dean and Kerry, began hinting that Lieberman should bow out; he hung on instead, protracting the run far past its natural expiration date in his first open show of intra-party defiance. “I don’t want to say ‘ridiculous,’ ” recalls one veteran of the campaign, “but there were people who thought he should get out for his own dignity.”

The 2004 debacle was Lieberman’s first introduction to a new force, the netroots, a loose collection of leftist blogs including MoveOn.org and DailyKos. The way the senator sees it, those groups have been “taking the party in a direction that’s bad for America: take-no-prisoners, partisan attack politics.” Their influence, he says, has made the Democrats “litmus-testy” and “reflexively antiwar.”

But Lieberman hadn’t felt the full wrath of the blogs until his 2006 reelection bid. Online activists, including the coalition Trippi had built for Dean, were united behind Ned Lamont, a young businessman with no national-office experience but a vocal antiwar stance. To Lieberman, the blogs’ power in online fund-raising and event organizing—and the vitriol used to fuel it all—came as a shock. (The senator’s own Website, by contrast, crashed on the eve of the primary; his campaign blamed it on Lamont hackers until an FBI probe concluded that shoddy programming was the culprit.) On August 8, 2006, Lamont won the primary with 52 percent of the vote. “For the sake of our state, our country, and my party,” proclaimed Lieberman, “I cannot and will not let that result stand.” The inclusion of “party” in that sentence was jaw-dropping. There would be no concession in the name of unity: Lieberman had anointed himself the savior of the party, and he had to quit it to save it.

Establishment Democrats like John Kerry and Connecticut’s own Chris Dodd, in keeping with the protocol and eager to score easy antiwar points, went on to back Lamont. (One Democratic senator who declined to endorse Lamont was Barack Obama, whose antiwar cred did not need polishing. Already one of the most popular faces on the Hill and a likely 2008 contender, Obama ended up making a series of high-profile appearances on Lieberman’s behalf during the primary.) Lieberman, of course, won the general election and, ironically, wound up holding the key to the Democrats’ Senate majority. The party was forced to forgive him, to an extent, but the embittered Lieberman had no reason to return the favor. In fact, his “decision to go indie came before the primary,” insists an insider. “Joe knew what he was going to do long before it became public. There were back-channel talks between Lamont and Dodd, Lamont and Kerry before the primary. Imagine, to have your friend John Kerry fly into Connecticut and campaign against you. To have your friend Chris Dodd film a TV ad against you. These are the people you have lunch with every Tuesday.” In other words, Lamont’s primary victory was not the cause of the final break between Lieberman and the Democratic Party. It was its consummation.

“Look, none of the Democratic candidates asked me for my support,” says Lieberman with a smile when I ask how he was approached by the McCain campaign. “John McCain called a week after Thanksgiving and said, ‘I don’t want to get you into more trouble with the Democrats than you’re already in, but would you consider endorsing me in New Hampshire?’ ” Lieberman recalls. “The media were asking whom I’d support, and I was in my wonderful status as an independent … ” He trails off dreamily, making it sound as if the endorsement just slipped out.

The real reason he’s backing McCain, Lieberman says, is because he believes in the kind of foreign policy that the Democrats don’t provide anymore: unflinching on Iraq, Iran, and Russia, and unfailingly loyal to Israel (he invokes Nixon’s line about “loading every plane” with weapons for Israel to explain what kind of president McCain will be). Lieberman believes foreign policy is the defining issue of the day, and sees Obama’s nomination as the regrettable result of a knee-jerk, blog-fueled peacenik mentality among the Democrats. “Last year, at the DailyKos convention, just about all of the candidates came, and the Democratic Leadership Council held a convention and none came,” he says. In July, following an online outcry, Lieberman notes, Obama called a second press conference in one day to clarify his position on Iraq troop withdrawal.

Lieberman’s rhetoric has been getting sharper-edged. His attacks on Obama, says Joe Trippi, “have gone way off the reservation.”

Lieberman sees this zigzag as evidence that Obama takes his marching orders from the blogs. “In 2007,” he tells me, “netroots and MoveOn.org controlled the agenda—they endorsed Obama like they endorsed Ned Lamont, and did to Hillary what they did to me in 2006.” Lieberman, who often brings up Lamont without provocation, seems to view the McCain-Obama matchup as his battle with Lamont writ large on the national canvas: a voice-of-reason maverick beholden to no one but his conscience pitted against a cocky line-cutter with no experience. “The lesson Joe learned about the netroots,” says a onetime colleague, “is now the frame he will put around any situation, even when it doesn’t apply.” An even less charitable view of Lieberman’s embrace of McCain holds that it’s all about payback for the way the Democrats treated him in the ’04 election and in Connecticut. “If you’re a nail, the whole world looks like a hammer,” says the same ex-colleague. “He was hurt, and to an extent, he is still working through it.”

Lieberman’s collaboration with the McCain campaign is informal but intense. He says he doesn’t normally receive note-by-note instructions, but he goes on talk shows, gives speeches, hosts fund-raisers, and travels extensively. “I give the McCain campaign days when I don’t have Senate,” he says. “Sundays and Mondays. I’m very pleased they’re going to use me at all.”

Lieberman’s allegiance switch plays nicely into the current popular outcry for bi-partisanship while undercutting Obama’s claim to the same. At the same time, his deep and hawkish foreign-policy record squares effectively with McCain’s strategy to position Obama as weak and inexperienced in foreign affairs. Lieberman recently toured Latin America and the Middle East with McCain, and when the bloody skirmish in Georgia aroused the ghosts of the Cold War, McCain sent Lieberman there as his emissary. The high-profile dispatch (the intended message seemed to be that McCain is already running a shadow Cabinet with an extra-tough-on-Russia stance) conveniently coincided with a rash of reports that Lieberman was being vetted for the vice-presidential slot.

Even if the rumor is merely a self-contained unofficial thank-you leaked by the McCain campaign, the thought experiment is irresistible. Leave aside, for a moment, that the same man who ran against Dick Cheney could hardly be anointed to succeed him without alienating vast constituencies and powerful donors. Or that common wisdom dictates that McCain has to appease people on his right, not on his left (where Lieberman, on most domestic nuts-and-bolts issues, still resides). Instead, recall that McCain himself, before he tacked right, was once discussed as a novel but not improbable VP for Kerry, and cheered Lieberman’s own 2004 run. The more you watch the two, the less unlikely the pairing seems. Trippi, for instance, is sold: “McCain needs to do something to shake this race up.” If he picks a standard-issue Republican, “his coalition is not going to be broad enough to win.” The kind of general campaign McCain could run with Lieberman at his side would likely be Bloombergian: We’re tired of polarization, we’re managerial and results-driven, and we’re going to work together to solve the country’s problems. Picking a functional Democrat would also give the McCain campaign license to tear into Obama while claiming objectivity. “This is a nonpartisan election,” mugs Trippi, launching into an imitation of Lieberman as the vice-presidential nominee, “but let me tell you, the Democrats have nominated a young man with no experience!”

Lieberman insists he’ll keep his convention speech positive and won’t turn into this year’s version of Zell Miller, the ostensible Democrat from Georgia whose saliva-spraying screed at the 2004 GOP convention managed to scare even Republicans. “Look,” he tells me, “I like Obama, I was in the civil-rights movement, I went to Mississippi to register voters. I’m not going to attack Senator Obama.” (He brought up the same patronizing line, more or less, at the Agudath dinner.)

The truth is, Lieberman’s rhetoric has been getting sharper-edged as the weeks tick by. Lately, he has taken to calling Obama “young man” and drawing Cheneylike scenarios of terrorists’ attacking the U.S. early into the new administration, the better to spook voters with Obama’s perceived inexperience. His attacks, says Trippi, “have gone way off the reservation.”

Right now, whatever respect Lieberman still commands inside the party comes from his position as the guarantor of the Democratic majority. Every sign, however, suggests that at least a few Senate seats will flip to blue in November. Disregarding the long-shot vice-presidency, Lieberman would then find himself in an odd position if McCain wins the election. No longer needing him for the majority, the Democrats will be practically compelled to punish him in some way. After Lieberman endorsed McCain, the DNC took away Lieberman’s superdelegate status, shrinking his influence on Connecticut’s presidential primary process to that of a mere mortal. (In response, Lieberman didn’t vote in the primary at all.) As a next step, the Democratic Steering Committee, chaired by Harry Reid, could strip him of his committee chairmanship if the full Senate ratifies it. A more graceful way out for everybody, says one Reid staffer, would be for McCain to appoint Lieberman secretary of Defense. “Then we’re spared a difficult decision.” But that doesn’t seem likely. As Leon Wieseltier, the literary editor of The New Republic and a Lieberman friend, drily notes, “I’m sure Joe would agree that, given the Muslim settings of possible American military action, having a Defense secretary named Lieberman may not be the shrewdest American move.”

And what if Obama wins? Should the Democrats pick up fewer seats than expected, they might be forced to look past the McCain episode and keep courting, or at least tolerating, an independent Lieberman. According to more than a few friends and colleagues, Lieberman might enjoy continuing to be a free-floating agent of lofty principle. After his primary defeat at the hands of Lamont, friends say, Lieberman talked a lot about being “liberated.” Then again, if the Democrats feel less than forgiving, or have cobbled together a filibuster-proof majority, “it’s going to be very difficult for Joe to operate with the Obama White House,” says an insider. “I don’t know what he’ll be doing in terms of his party affiliation.”

Of course, the senator could always complete his narrative arc in style and re-reregister as a Republican. In the case of an Obama victory, this would probably mean joining an outgunned minority, and most party defections go the other way. But most politicians don’t endorse presidential contenders across party lines, either.

In fact, the Republicans have already come calling for their favorite Democrat more than once, and there are some signs that Lieberman is listening. Senator Richard Shelby of Alabama, who flipped in 1994 to join the Gingrich Revolution, says Lieberman has chatted with him about his experience switching parties. “I’ve told him many times I’d love to see him in the GOP,” he drawls. “We’d have the majority right now.” The procedure itself, Shelby says, is purely symbolic. “You don’t have to sign anything. I just held a press conference and said, ‘I’m changing parties.’ It was the easiest political thing I’ve done in my life.”