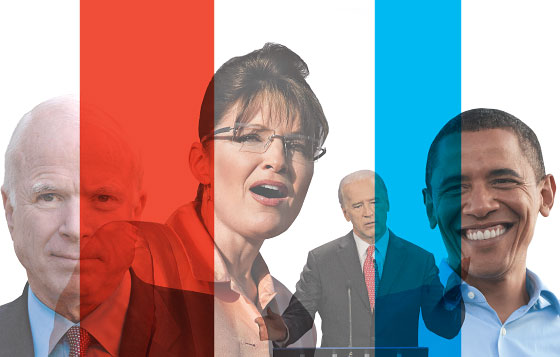

By the time Sarah Palin took the stage last week at the Xcel Energy Center in St. Paul, Minnesota, her selection as John McCain’s running mate was looking like an even bigger gamble than when he’d announced it a few days earlier—and, hoo boy, that was saying something, since from the outset it seemed as if McCain had laid down his life savings on a million-to-one shot. The reaction of professional Republicans to the Palin pick fell somewhere along a continuum between shock and incredulity. Her résumé was tissue-thin and lacking even the faintest trace of national-security credentials. McCain barely knew her. The process by which she’d been vetted was hasty, half-assed, haphazard. Her rollout began with the announcement, on the first morning of the Republican convention, that her teenage daughter was pregnant. A steady drip-drip-drip of revelations about her past associations (with a Jews-for-Jesus preacher, a fringe political party, Pat Buchanan) and alleged ethical transgressions had the press scenting blood in the water. Reporters quickly hightailed it to Alaska. So did teams of Democratic opposition researchers and Republican lawyers. “It’s the worst mishandling of a V.P. choice since McGovern tapped Eagleton,” said a prominent GOP strategist. “I’ll bet she is off the ticket inside of ten days.”

Yet the roar of approval was deafening inside the hall when Palin strode to the podium. The faithful, fueled by resentment toward the “liberal media”—at one point the delegates chanted “Shame on you” in the general direction of an aghast Gwen Ifill—over its treatment of her, wanted her to wow them. And she did. She was glamorous, confident, homespun, sassy, snarky, and unafraid to wield the stiletto. In fact, she seemed to delight in plunging it into Barack Obama’s kidneys. She said that being a small-town mayor was kinda like being a community organizer, “except that you have actual responsibilities.” She sneered that a presidential campaign isn’t “a journey of personal discovery.” She called Obama an elitist, an egotist, a taxer, a spender, an accomplishment-free zone. By the end, you had no doubt why they call her Sarah Barracuda.

How well the baring of Palin’s teeth played in America-land was difficult to gauge. But the thumbs-up verdict in the hall was nearly universal and was seconded by the panjandrums of the political-media industrial complex. As NBC’s Chuck Todd crisply put it, “Conservatives have found their Obama.”

The Palin prelection was more than a terrific performance, however. It was a revelation—not about Ms. Barracuda but about her new boss and how he intends to wage the fall campaign. According to people close to the McCain operation, the Arizona senator’s veep deliberations were driven by a signal insight provided by his ever-pessimistic pollster, Bill McInturff: that unless McCain did something dramatic to alter the dynamics of the race, he was doomed. McCain’s preferred game-changer, by all accounts, was pro-choice, independent senator Joe Lieberman, who would enable him to reclaim his maverick status, distance himself from George W. Bush, and make a bid for moderate undecided voters. But then McCain was informed by Karl Rove and others that a pro-choice V.P. would never be affirmed at the GOP convention. With Mitt Romney and Tim Pawlenty deemed insufficiently transformative, McCain reached back and heaved the ball downfield in the direction of Sarah Palin.

The implications of McCain’s Hail Mary were puzzling at a glance. Was he trying to reposition himself as a reformer? To reel in disaffected supporters of Hillary Clinton? Maybe, maybe. But now that the smoke has cleared and the Republican convention is history, there’s no escaping the meaning of McCain’s embrace of a gun-toting, pro-life, anti-sex-ed, possibly creationist running mate: that his general-election strategy is modeled on the one authored by Rove on behalf of Bush in 2004. A strategy, that is, that revolves around revving up and turning out the party’s base. Around God and guns and abortion and family values—a revival of the culture wars—combined with a withering onslaught to render Obama unacceptable.

That McCain eventually wound up here should come as a less than total surprise, for the guru guiding his message and strategy is Steve Schmidt, who made his bones working for Rove in 2004. Schmidt is regarded as one of the toughest, savviest, most skilled operatives in the business—but his mettle will be severely tested by his opposite number on Team Obama, David Axelrod, the class of the Democratic field. For months already, the two men have faced off like a pair of chess grand masters, carefully arranging their pieces on the board, occasionally snatching a pawn or a rook, setting up their candidates for the final drive to capture the other side’s king.

For Schmidt and Axelrod, that final drive began two weeks ago, when the campaign entered a period hectic, pivotal, and historically unprecedented: Never before in modern presidential politics had the parties’ nominees named their running mates, staged their conventions, and given the most widely viewed speeches of the election in so compressed a time frame. What neither adviser expected was that McCain, in the midst of this mad flurry of events, would upend their chessboard with a move as radical as the Palin pick, turning what had seemed likely to be a bizarro replay of the Clinton-Obama fight—change versus experience—into a very different kind of contest. The kind of bitterly polarized affair from which Obama and McCain once seemed to offer a respite. The kind that feels all too achingly familiar, and thus quite terrifying.

At 37, with a 225-pound frame, a Kojak-bald head, wraparound shades, and a Bluetooth headset invariably jacked into his ear, Schmidt cuts an imposing figure. His affect, which alternates between steely, monotonal stoicism and fierce combativeness, is cultivated, designed to be intimidating. His cardinal professional virtues are relentlessness, focus, and a capacity for nearly infinite repetition. The GOP consultant Alex Castellanos says Schmidt is more purely pragmatic than Rove, less ideological, and hence even more lethal—“the perfect political killing machine.” His former boss accordingly nicknamed him The Bullet. His current one ritually refers to him as Sergeant Schmidt.

The bond between Schmidt and McCain was formed a year ago, in the wake of the near immolation of the McCain campaign in a bonfire of chaos, indiscipline, and mismanagement. Schmidt and his family lived in California, where he’d helped engineer Arnold Schwarzenegger’s landslide reelection in 2006. Even as McCain’s campaign faltered, he stuck loyally by his side. “He earned his stripes in the foxhole,” recalls McCain’s former media adviser Mark McKinnon. “He talked to McCain when no one was returning his phone calls.”

But it wasn’t until June that Schmidt assumed near-total control over McCain-land, after confronting the candidate over what he perceived as an incipient crisis similar to the one in 2007. The lack of focus. The internecine strife. The sloppy, listing message. Schmidt informed McCain bluntly that if he didn’t make significant changes in his operation, he was going to lose.

Ten days later, Schmidt was in charge—or so it seemed. For at the same time, McCain was whispering to Mike Murphy, the strategist who had run his primary bid in 2000, about bringing him back into the fold as chief strategist. Schmidt made clear that he would tolerate no such thing.

Schmidt’s victory in that power struggle proved a turning point. Imbued with new discipline—Schmidt sharply curtailed McCain’s formerly wide-open access to reporters, which was only getting him in trouble as he experienced more senior moments, and even restricted his cell-phone usage, to cut down on unhelpful kibitzing—the campaign found a groove and also a lucid message.

“Steve is a message machine,” says McKinnon. “He knows you have to distill the race down to a very simple frame. And the frame they finally found their way to was McCain equals country first, Obama equals Obama first. They struggled for a while to get their arms around it. They rolled out liberal, they rolled out flip-flopper, they test-drove various strategies. Then they hit on this idea of Obama as a celebrity who is unready to lead. It works because it has a ring of truth—and it’s incredibly hard to defend against, since you’re basically being attacked for being popular.”

Obama’s trip abroad this summer was both a catalyst for this message and a target-rich environment for Schmidt. At the end of July, the campaign let fly with a series of controversial negative ads mocking Obama for his megastar status, his alleged messianism, his placement of ambition above the good of the commonweal. Many of McCain’s former advisers from 2000, such as Murphy and John Weaver, criticized the spots. “They have a strategy, at least that’s something,” Weaver told me at the time. “But if you’re gonna make a negative charge, it has to be credible. And I don’t think these pass the basic smell test.”

Maybe so, but judging by every available metric, the charges seemed to stick. By the end of August, after a monthlong string of harsh TV spots, the national polls began to tighten, with McCain pulling almost level with Obama in most surveys and even ahead in some. Similar signs of movement were apparent in several pivotal battleground states. Meanwhile, Obama’s negatives were rising appreciably, with no discernible cost to McCain’s own favorability ratings.

The story behind this story was that Schmidt and his people had come to believe that, for all the talk of the Obamans about expanding the electoral map, there were few traditionally red states in which the McCain camp had reason for concern. Although the Obama forces were pouring money into such places as Missouri and Montana, it seemed to be having little effect. Moreover, McCain turned out to have more money at his disposal than many assumed he would. Taken together, these two facts allowed Team McCain actually to outspend Team Obama in a number of swing states.

Closing the gap built confidence among party regulars that Schmidt was up to the task of running a national campaign. And it suggested to the Republican base that McCain could conceivably win. On the eve of the Democratic convention, Castellanos told me, “I think right now it’s pretty clear that the race is McCain’s to lose—which, under the circumstances in the country, is pretty amazing.”

Other Republicans, however, were a good deal less sanguine. “If it’s 45-45, we are losing; we are the incumbent party,” says a longtime Republican consultant. “McCain is already harvesting a disproportionate share of voters who say the country is on the wrong track. And yet he’s still never consistently been above 45 percent. The McCain guys haven’t succeeded in articulating an overarching positive theme. Schmidt is good at winning the next twelve hours but not at building up a brand. They’ve spent the same amount of money as, or even more than, Obama—and now, with McCain taking public money, they’re about to be outspent three to one. That explains why the Obama people aren’t panicking. And why they shouldn’t be.”

Panic is not David Axelrod’s style, though he confesses to always being a bit twitchy, as a matter of professional duty. “I get paid to be nervous,” he says.

Axelrod is 53, lives in Chicago, and has been advising candidates since 1984, when he abandoned political journalism in favor of political consulting. His clients have included both Clintons (for his presidential reelection in 1996 and her Senate run in 2000), John Edwards in 2004, and Richard Daley, along with countless local black candidates across the country. In the trade, Axelrod is known for being averse to issues and policy, for preferring to focus on softer qualities of character, biography. “His brilliance is his ability to communicate emotionally with voters about his candidates, to bring out what makes them personally compelling and drive a larger narrative based on that,” says Hillary Clinton’s former communications czar, Howard Wolfson. “But he also has the ability and willingness to twist the knife when it’s appropriate.”

Twisting the knife without looking nasty was central to Obama’s success against Clinton in the Democratic-nomination fight. “The positioning of their whole campaign was negative, an implicit critique of her character,” Wolfson says. “David had seen the focus-group data from his work with us in 2000. He knew where her soft spots were, where the underbelly was: the doubts among voters about her as ambitious, calculating, triangulating. And he figured out early on how to juxtapose that perfectly against the brand they were building for Obama, how to attack her without even mentioning her name.”

But after slaying the Clinton dragon, Axelrod and his team seemed to fall prey either to exhaustion or complacency. As summer wore on and McCain gained ground, waves of concern, then nervousness, then agitation began bubbling up among party insiders. “Their anti-McCain messaging is nowhere,” a Democratic player complained in mid-August. “People say that they’re not being tough enough, but toughness isn’t the issue. Presidential campaigns are all about storytelling: You tell a story about yourself and a story about your opponent. But they’re not telling a story about McCain—and there’s a hell of a story to tell.” At the same time, Axelrod and his team appeared to underestimate the salience of the story the McCainiacs were spinning about Obama. In the face of the Republican nominee’s outrageous claim, while Obama was in the Middle East, that the Democrat “would rather lose a war in order to win a political campaign,” Obama’s response was startlingly wan: He was “disappointed” in McCain. And the ads taunting Obama as a political Paris Hilton and as The One elicited little more than scoffing dismissal from the folks out in Chicago.

Axelrod insists McCain’s August assault was predictable and predicted. “I told Obama when we went overseas that the trip would be of long-term value but would create short-term problems for us politically—and they did,” he says. “The other guys exploited the situation pretty effectively. They had a good couple of weeks. I thought they were pretty clever. But did I start saying this is slipping away? No.”

Axelrod’s sense of confidence was informed by his experience in 2007. For much of that year, Obama lagged Clinton by double-digit margins in the national polls. The campaign’s donors became restive, began insisting that the hopemonger had to kneecap the queen—and the press chimed in with similar shopworn advice. But Axelrod and Obama’s campaign manager, David Plouffe, kept their eyes on the prize: the Iowa caucuses. They had a plan and intended to stick to it come hell or high water. The plan was centered on an audacious turnout operation in the Hawkeye State, and also on Obama’s delivering a roof-raising, galvanizing speech at the Iowa Jefferson Jackson dinner in November, the traditional kickoff of the home stretch before the caucuses.

To no small extent, Axelrod and Plouffe viewed the run-up to the general election as 2007 all over again. Rather than being distracted by national polls, they focused on the numbers in the seventeen states where they were targeting resources. Rather than heeding calls for Obama to plunge into the mud, they attempted to preserve his new-politics brand. And they looked ahead to the Democratic convention as a kind of national J-J. “Especially with the convention coming so late,” says Axelrod, “we saw it as our chance to frame the case, and if we could do that, we thought it would give us incredible momentum going forward.”

Axelrod regarded the first three days of the convention as being almost as important as Obama’s speech. His fingerprints could be found on nearly every address that was delivered, and the whole event proceeded according to a master plan devised by him. Monday revolved around the nominee’s bio, Tuesday around the economy, and Wednesday around national security, each session building to the Obama oration—the draft of which wasn’t finalized until three hours before he gave it, giving him time to rehearse it only twice—on Thursday. When it was all over, I asked if Axelrod believed the convention had framed the election in as dead-simple, crystal-clear terms as the Republicans’ country-first/Obama-first dichotomy. “I do,” Axelrod said. “Our frame is this: McCain offers more of the same, and Obama offers the change that we need.”

After Obama’s tour de force, it was difficult to dispute that assessment—and easy to forget the anxious murmurs among professional Democrats out in Denver. On the convention’s first night, two of the party’s most influential message-meisters, James Carville and Paul Begala, lambasted the proceedings as watery and weak-kneed. And just a few hours before Obama killed at Invesco Field, a panel of leading pollsters and media savants lamented the lack of clarity of Obama’s positioning. Was he saying that he’s the future and McCain’s the past—or that he’s one of you and McCain is one of them? Was he still a post-partisan reformer or a middle-class populist? “I still don’t think he’s defined the election, the choice, in a big way,” said pollster Stan Greenberg. “It’s astonishing that he hasn’t at this point.”

Maybe this is all premature and pointless Democratic hand-wringing—an occurrence about as unusual as the sun rising in the east. But it’s nothing compared to the fear and trembling that might soon be coming to a liberal household near you. “I’ll tell you one thing,” Wolfson says. “If McCain comes out of his convention ahead in the polls, an awful lot of Democrats are going to be running for the windows.”

When Joe Scarborough first heard the news that McCain might be plucking Palin out of obscurity and placing her on the ticket, he scoffed, “Yeah, that will not work.” It was the morning after Obama’s speech, not long past 6 a.m., at the Denver diner that was serving as the makeshift set for MSNBC’s Morning Joe. A few minutes earlier, Time’s Mark Halperin had staggered in, muttering something under his breath about a chartered jet from Alaska to Arizona—and the next thing you knew, it was true. Mike Murphy looked poleaxed. Pat Buchanan mused that Palin would be “eaten alive in a debate with Joe Biden.”

A few miles away, on the tarmac at Denver airport, Axelrod was onboard the Obama campaign jet, waiting to take off for Pittsburgh with his boss and Biden. His initial reaction: “astonishment,” he recalls. “She hadn’t been on anyone’s list. She’d just been a governor for eighteen months, and before that mayor of this tiny town.”

Palin’s political inexperience was just part of the weirdness of the pick. There was the fact that McCain had only met her once before flying her down to his place in Sedona to offer her the gig. There was the fact that his aides seemed as shocked and baffled by the pick as he rest of the Republican Party. There was her somewhat outré background: the five colleges, the beauty-queen thing, the sportscaster thing, the passion for weapons, the taste for mooseburgers. There was her part-Eskimo, snowmobiling husband. And then there were those crazy rumors flying around the Web: that her infant son, Trig, who has Down syndrome, might really be her teenage daughter’s.

“The McCain people are freaking out, they don’t know what to believe,” a veteran Republican operative said on the eve of the Republican Convention. “But she’s clearly not qualified to be president. She clearly hasn’t been vetted properly. I mean, who is this woman?”

It would take them a bit more than a weekend to figure out an answer to that question. Late in the morning of the convention’s first day, the McCain camp released its explosive statement about the pregnancy of Palin’s 17-year-old daughter, Bristol. Schmidt descended into the basement media holding pen in the Xcel Center—and discovered that what he’d really waded into was a press-corps piranha pool. The swarm of reporters around Schmidt was large, loud, and insistent. When and how had McCain learned that Bristol was with child? How comprehensively had his V.P. choice been vetted? Would the fact of Bristol’s pregnancy, along with the care required by baby Trig, compromise her ability to perform as McCain’s running mate or vice-president?

Calmly, forcefully, precisely, mechanically, like Roger Federer tearing up the baseline at Flushing Meadows, Schmidt swatted back every query fired at him. McCain had been “aware of this private family matter” since “last week” (though he wouldn’t say precisely when). The vet was “thorough” (though he offered no details). “Life happens in families,” Schmidt went on. “If people try to politicize this, the American people will be appalled.” As for Palin’s capacity to serve effectively, Schmidt, ginning up his highest dudgeon, declared, “I can’t imagine that question being asked of a man. It’s offensive.”

The performance was vintage Schmidt, a deft admixture of minimalism, mau-mauing, and faux outrage. But man, oh, man, did the guy look miserable delivering it—and who could blame him? Already Gustav had derailed the opening day of the convention. And now, rather than building up McCain or tearing down Obama, Schmidt found himself scrambling to defend a V.P. nominee who seemed, at that moment, potentially indefensible.

Within 24 hours, however, Schmidt’s posture had shifted from defense to offense, to waging war on the media—a time-honored tactic that Schmidt has turned into an art form. He inveighed against the New York Times. Against the left-wing blogosphere. Against (unnamed) reporters who he claimed (without a scintilla of evidence) asked if Palin would undergo a paternity test for Trig. Against the “smear after smear after smear” being pursued by a press corps “on a mission to destroy” her. Against the “old-boys’ network that has come to dominate the news Establishment.” Some commentators believed that Schmidt was genuinely angry. Others suggested he was working the refs. But the truth was that he had only one objective in mind: to rally the delegates in the hall around Palin as a victim of the elite, uppity, anti-conservative media. And in this he manifestly succeeded.

What at first seemed to be an ad hoc adaptation will now almost certainly become a full-blown Agnewian strategy. For one thing, few ostensible depredations arouse the passions of rank-and-file Republicans, not to mention right-wing talk-radio hosts, more than liberal media bias. For another, the imputations of such bias create a convenient pretext for shielding Palin from rigorous press scrutiny—hard questions about foreign affairs and domestic policy that there is no plausible reason to believe she is currently competent to answer. On the morning after her speech, in fact, former Bush aide and Schmidt ally Nicole Wallace, appearing on Morning Joe with Time’s Jay Carney, provided a vivid preview of how the McCain side is likely to turn denying access to Palin into a pseudo-populist cause:

CARNEY: “We don’t know yet, and we won’t know until you guys allow her to take questions, can she answer tough questions about domestic policy, foreign policy … ”

WALLACE: “But I mean, like, from who? From you?”

CARNEY: “Yeah, from me.”

WALLACE: “Who cares? No offense.”

CARNEY: “Who cares? I think the American people care.”

WALLACE: “The American people want to see her. Who cares if she can talk to Time magazine? She can talk to the American people.”

The irony is that much of the media’s skepticism about Palin was stoked by Republican sources who believed her manifestly unqualified for the V.P. slot, and that her selection was politically damaging to McCain. “They have spent months making the argument that Obama is dangerously inexperienced, that the White House is no place for on-the-job training,” explains one Republican media savant. “And now they’ve put this woman on the ticket who didn’t have a passport until a year ago? How can they now come back and say Obama isn’t ready? He looks like Colin Powell compared to her.” This person went on: “The one thing the Republican brand had left was national security. And now it’s, ‘Hey, she likes guns, let’s put her in line to be commander-in-chief!’ It’s absurd.”

Most Democrats concurred that by picking Palin, McCain was forfeiting the experience argument. But one of the party’s sharpest strategists disagreed. “The construct is this: Would you rather have a vice-president with limited experience or a president with comparably limited experience, possibly less, depending on how you define experience?” this person e-mailed to me. “The irony is that Obama made this both possible and plausible. Given this, McCain can and should continue to argue ‘ready to lead’—and I daresay he will with effectiveness. And I think the Obama team is making a mistake if they press this issue, because then the race becomes about experience, which is exactly what McCain wants.”

He certainly seems to—and so does Schmidt, who vigorously contended to Katie Couric that Palin “is more experienced and more accomplished than Senator Obama.” Asked to justify the claim, Schmidt replied, “Well, Barack Obama was in the United States Senate for one year before he took off … to run for president full time. He was a state senator, he had no executive decisions. And 130 times [on] tough votes, he took a pass and voted present. Leaders have to make decisions. Governor Palin makes decisions.”

Palin herself, of course, derided Obama’s experience in her speech, in particular his stint as a community organizer—which is no wonder, given that occupation’s urban (read black, read poor, read black poor) connotations. Yet for all of Palin’s comfort in playing the lipstick-wearing pit bull, her most important role in the campaign ahead will not be mauling Obama. It will be energizing the party’s base. As The Atlantic’s Marc Ambinder reported, the McCain scheduling squad is “filling a calendar that will find her deployed to places where McCain can’t go, places where McCain’s gone and fallen flat, and places where social conservatives need an enthusiasm boost.” The goal here is straightforward: increase Evangelical turnout to Bush-like levels, in order to more or less solidify the 2004 electoral map.

But by riling up and nailing down the base, Palin performs an even more valuable function for McCain: She allows him to ignore the wingnuts and sprint hard toward the center. To focus on issues where McCain’s positions appeal to moderate and independent voters. To spend the lion’s share of his time in the handful of states on which the election will turn: the traditional battlegrounds, such as Ohio; the new ones, such as Virginia and Colorado; and also one or two blue states, namely Michigan and Pennsylvania, that Schmidt thinks might be within McCain’s grasp. It was no coincidence that the day after the convention, the new Republican ticket headed to Macomb County, outside Detroit.

These calculations undergirded almost every element of McCain’s own speech to the convention. The only time the Republican standard-bearer uttered the surname Bush, he was referring to Laura. (McCain was by no means unique on this score; that four-letter expletive was used only seven times over the course of the convention.) Only thrice did he utter the word Republican: once in relation to Sarah Palin, and twice in the context of decrying corruption. The speech was themeless, meandering, stirring only in its biographical passages. But its central political thrust was an appeal to bi-partisanship. “Again and again, I’ve worked with members of both parties to fix problems that need to be fixed,” McCain said. “That’s how I will govern as president. I will reach out my hand to anyone to help me get this country moving again. … Instead of rejecting good ideas because we didn’t think of them first, let’s use the best ideas from both sides. Instead of fighting over who gets the credit, let’s try sharing it. This amazing country can do anything we put our minds to. I will ask Democrats and independents to serve with me.”

The speech, in other words, was an attempt to revive the McCain brand of old: the reformer, the change agent, the maverick. This task is essential for McCain to have a chance to win in November; he needs to pick off sufficient numbers of independent voters to turn back the Democratic tide. A pure-base strategy will not do—as Schmidt is well aware. “Don’t make the mistake of thinking that Steve only knows how to do base politics,” explains Dan Schnur, McCain’s communications director in 2000, who is based now in California. “The campaign he ran out here for Arnold was all about persuading undecided voters, many of them independents. He knows how to do that too.”

The question is whether the Obama campaign will let McCain seize the center. “All summer everyone assumed that this race would be decided by whether McCain could bring down Obama,” says Alex Castellanos. “But I think that’s already happened. They’ve cut him open. They know how to make him bleed. Now I think what’s really going to determine the outcome of this race is whether Obama can bring down McCain.”

The night before the Republican convention got under way, Axelrod was still marveling at the audacity of the Palin pick, delighting in the opening it gave him to tear Obama’s opponent a new one. “McCain has completely subverted his own argument that the most important thing that you need to be president is vast foreign-policy and national-security experience,” he said. He named someone who could very well be president one day—a third of all the people who have been V.P. wind up as president—who has no such experience. It kinda makes a mockery of his slogan ‘Country first.’ This was a politics-first decision.”

By the time the GOP convention was over, however, Axelrod was telling the New York Times that Obama would not challenge Palin’s experience. And the campaign, plainly flummoxed, was struggling to calibrate an appropriate stance toward her and the array of forces her nomination had unexpectedly let loose. In Palin, the Obama people found themselves confronting something which they have no experience: a phenomenon so new and fascinating to the press and the public that it threatens to eclipse even their boss. The hard-right views were contained in a disarming, charismatic package. And attacking would be much more complicated than it first appeared. Thus, one school of thought was simply to ignore her.

“They need to put Palin in the rearview mirror,” says one Democratic strategist. “Let other people blab about it. They’ve got just one job over the next two months: Talk about Barack Obama to undecided voters. If she’s as screwy as she seems, she’ll take care of herself.”

The possibility of a Palin implosion is real enough. Rumors about her past are swirling. If Schmidt and his associates ever deign to let her meet the national press, she might prove to be a gaffe machine. Her October 2 debate with Joe Biden could leave her shredded in pieces on the floor. (Or, unless Biden keeps his tongue under control, it could be the moment when Obama thinks the unthinkable: Man, I wish I’d gone with Hillary.)

But as the afterglow of Palin’s speech faded, the contours of the battlefield—and possible lines of attack—began to reemerge. As Axelrod noted to me, the troubling thing about the Palin pick isn’t Palin—it’s what the choice says about McCain. About how he makes decisions. His impetuousness. His rashness. His recklessness. His unpredictable leadership style. “It’s McCain as the unreliable Republican,” says one leading political ad-maker. “The subtext is already there. He’s spent years selling you the maverick brand. That’s one side of the coin. All you have to do is flip the coin over and it’s there: the dark side of maverick. ‘You never know what he’ll do next.’ ”

And concerns about McCain’s age, a subject that heretofore the Obama campaign has had to approach with extreme care, are brought closer to the surface by Palin’s youth and lack of experience. Two days after the announcement that Saracuda was boarding the Straight Talk Express, the pollster Frank Luntz convened a focus group of undecided voters. When asked about the freshly minted V.P. nominee, one woman—a Hillary voter then leaning in McCain’s direction—said, according to Time’s Joe Klein, “[McCain’s] age didn’t really bother me until he picked Palin. What if he dies in office and leaves us with her as president?”

When I asked Axelrod if he was willing to go there, on either recklessness or age, he declines to answer. But in a way, he already has. After McCain badly botched a question last month from a reporter about his real-estate portfolio, the Obama campaign uncorked an ad in which the narrator intones, “When asked how many houses he owns, McCain lost track, he couldn’t remember”—an ad that fairly screamed old, old, old. Meanwhile, in his speech in Denver, Obama himself declared that he was ready to debate McCain over who has the “temperament” to be commander-in-chief. Hothead, anyone?

What Axelrod is willing to discuss are the ways in which he believes that Palin has altered the terrain on which the election will be contested. “The pick has shifted their message to reform,” he says. “McCain is trying to recapture the outsider lane. They’ll try to portray us as the candidate of the conventional Democratic Party liberal orthodoxy. They’ll hit us on the issues they always do, like taxes.” Axelrod goes on: “The goal for us is to keep the focus on the center ring, which is, ‘You’re complicit in the policies that are killing people, and you want to continue them because you say that they are working.’ We’re gonna continue to hammer away on that.”

McCain’s decision to shore up his base by teaming up with Palin should make it easier, not harder, for Axelrod and his people to define McCain as a Republican. And though the Alaska governor’s presence on the ticket has plainly goosed the hard right, it has also jolted the Democratic ranks. (Some $10 million flowed into Obama’s coffers on the heels of Palin’s speech.) In a year like this—with the economy in disarray, the Republican brand dead on its feet, and 80 percent of the electorate deeming the country to be on the wrong track—a base-on-base election plainly favors the Democrats, so long as they play their cards right.

The problem for Obama is that it’s been a good long while, convention aside, since he and his team have done that. For all the jabber about Palin’s gender, the more relevant political fact about her may be her working-class appeal, and the working class has never exactly been Obama’s sweet spot. And though part of that may be owed to the dexterity of Schmidt et al. in branding him a celebrelitist, a bigger part can be put down to his consistent, maddening failure to conjure a compelling economic narrative on which to hang his policy proposals. And that in turn has handed the Republicans an opportunity: to highlight culture over economics.

Or, put more bluntly, to restart the culture wars. It required no great perspicacity to see this was what the Republicans were up to last week in St. Paul. The signposts were everywhere and garish. Here was Fred Thompson, essentially accusing Obama of being in favor of infanticide. Here was Rudy Giuliani at his feral, bloodlusty, sarcasmagoric worst. “I’m sorry that Barack Obama feels that [Palin’s] hometown isn’t cosmopolitan enough,” snarled the mayor. “Maybe they cling to religion there.” And here was Palin, rhetorically attaching sandals to Obama’s feet, draping beads around his neck, and placing an ACLU membership card in his back pocket. “Al Qaeda terrorists still plot to inflict catastrophic harm on America,” she said, “and he’s worried that someone won’t read them their rights.”

The script was old, the act was tried, the performances ludicrous to the point of being comical. And the whole ugly circus was made all the more ridiculous by the performance of McCain calling for unity amid the howling hyenas, grinding his way through a speech text whose archaic cadences, if read by someone remotely capable, would sound like something from the mouth of Henry Clay or John Calhoun. A performance, that is, so at odds with the others at the convention, and with Palin’s in particular, that if you actually tried to reconcile them in your mind, the titanic degree of cognitive dissonance would make your head explode.

But there is a reason the Republicans keep falling back, again and again, on such hoary tropes. The reason is that, from the age of Nixon to the era of Lee Atwater to our current (yes, apparently, it’s not dead yet) epoch of Rove, they have all too often worked. Us versus them is a potent message—and one tailor-made to a candidate with the name Barack Hussein Obama. Who, need it really be pointed out, is plainly not like you.

Will it work again? Who knows? With the emergence of Sarah Palin as the wild card in this year’s race, we are once again in this mind-bending election year wandering around, deep in the wilds of political terra incognita. She is one of those plot twists too incredible even for Hollywood. “Anyone who says they can tell you how it’s all going to play out, how the pieces all fit together in a presidential campaign, is kidding you,” Axelrod says. “You can’t really understand the story until it’s written.”