When Barack Obama made his final push for a health-care bill last month, he successfully appealed to the better angels of those who serve in the House. But one peek in the Senate across the way, and it was clear the hell-raisers were still putting up a valiant fight. Within 24 hours of the House vote, John McCain told an Arizona radio affiliate that people should expect no cooperation with Democrats for the rest of the year: “They have poisoned the well in what they’ve done and how they’ve done it.” Two days after that, Republicans were shutting down committee hearings, and as soon as they got the fixed health-care bill from the House—which Democrats hoped to pass in pristine form, since that would send it straight to the president’s desk—they tacked on 41 juicy amendments, most of them imaginatively conceived to humiliate the Democrats (like Tom Coburn’s now-famous proposal to deny sex offenders federally funded Viagra).

I visited the Senate on the last day it was considering those 41 amendments. The nearly daylong marathon, unofficially known as Vote-o-Rama, had taken its toll: There were bags under the men’s eyes and the women’s faces weren’t quite the perfect frescoes of makeup they usually are. The senators had been there until 2:45 the night before, and here they all were again, at 9:45. “It’s very partisan, and it’s not fun, and it’s not productive,” conceded Jon Kyl, the minority whip, as he raced to a meeting.

So why bother, if it’s infuriating even to you?

“You hope for a better day,” he said, and hurried on.

For all the fine effort that Barack Obama and House Speaker Nancy Pelosi put into passing health-care reform, its success was really a fluke as far as the Senate is concerned. The measure squeaked through on the basis of an exception (a fleeting Democratic supermajority) and a technicality (reconciliation requires only 50 votes). Before that, the Senate of the 111th Congress had been an awesomely inefficient body, threatening the most filibusters and reauthorizing appallingly few bills; almost every Democrat had a story about legislation held hostage. This October, when Jeanne Shaheen, the newly elected senator from New Hampshire, attempted to pass a measure extending unemployment benefits, it spent a month in limbo (holds, objections, etc.) before the Senate passed it by a vote of 98-0, suggesting lawmakers spent a full month dickering over a measure that pretty much everyone agreed to from the start. “The extent to which the Senate rules keep things from happening has been a little surprising,” Shaheen told me when I asked her about it. “That, and the partisanship.”

And this gridlocked mode is just where the Senate found itself when it concluded its business ten days ago—with Vote-o-Rama, bleak predictions about the future of bi-partisanship, and (for good measure) Coburn rolling in front of another attempt to extend federal unemployment benefits. And that is likely where the Senate will find itself when members come back from recess next week.

All of which makes you wonder: What exactly are these people here for? Why are ordinarily productive legislators like John McCain saying they’re essentially on strike? “That’s the most exaggerated report in history,” says McCain when I ask him. “The fact is, they won’t cooperate on things that they want in order to get their agenda done.”

When Obama was stumping for health-care legislation, he put this very question to lawmakers: Did you come to Washington to do anything? Or did you come here for silly season? In fact, it was a senator, South Carolina’s Jim DeMint, who gave Obama an assist in crystallizing this question in the first place, by making political hay of health-care reform in a conference call: “If we’re able to stop Obama on this, it will be his Waterloo. It will break him.”

Of course, it’s the Senate Republicans’ prerogative to thwart or vote against Obama’s initiatives. For many of them, it’s as much a matter of principle as politics. (If the shoe were on the other foot, and Senate Democrats were working en masse to block tax cuts for the superrich, they’d surely claim it was out of principle.) Many of them didn’t come to the Senate to pass Obama’s version of a climate-change bill or immigration reform, and some, like McCain, are facing a difficult primary challenge from the tea-party right. But in the aftermath of the startling passage of health-care reform, both parties now find themselves at a crucial juncture, struggling to arrive at the right balance between kowtowing to their bases and trying to govern. The Republicans must decide whether to collaborate with the Democrats or obstruct them. The Democrats must decide whether they’ll nudge closer to the middle in order to pass legislation, or hew closely to their ideals and gain political points by characterizing the GOP as the Party of No. Whatever each side decides, all eyes will be on the Senate: Because of the chamber’s rules, it has far more power to thwart legislation than the House.

Photograph by Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

So far, obstruction is winning. The Monday before Vote-o-Rama, the Banking Committee declined a chance to form a bi-partisan deal to reform Wall Street, a decision that Bob Corker, a Tennessee Republican, called “a major strategic error.” Wall Street reform may still squeak through. But Kyl put the odds of passing legislation on climate change and immigration reform, Obama’s other top priorities, at “almost zero.” (This was before Obama gave the nod to offshore drilling, to be fair. But still.) I asked McCain how the bi-partisan agreement on immigration had fallen apart, seeing that he and Ted Kennedy had worked so hard on this issue. “The Democrats won’t accept a temporary legal-worker program!” he said, as he went to vote for the umpteenth time. “The unions are opposed!”

Which suggests that the two parties are more inclined to bicker at this point than get along, all at a moment of huge popular discontent. During Vote-o-Rama, even senators with histories of bi-partisanship were playing an enthusiastic role in the obstructionist theatrics. I asked Bob Bennett, a mild-mannered older Republican from Utah whose father had also served in the chamber, why that was the case. He was offering one of the more lurid amendments—a provision that would force the residents of D.C. to define marriage—but at least I understood why: He too is facing several challenges from the tea-party right back home. But how could he explain the participation in this cynical orgy by his nonvulnerable colleagues?

“Well, there are people who enjoy the game,” he said. “And people who enjoy the game get in the game.”

But the Senate is supposed to be above the game, I tell him, at least in the election off-season. Richard Russell, the legendary Democrat from Georgia, had a saying—

“I know,” he said. “My father used to quote it: ‘The Senate allows you two years as a statesman, two years as a politician, and two years as a demagogue.’ ” He gave me a wistful look right then, and proceeded to say exactly what I’d been thinking. “And that’s actually changed. You’re now a demagogue the full six years.”

In the opening pages of Master of the Senate, Robert Caro elegantly explains what the framers had originally designed the upper chamber of Congress to be. First, and most famously, the Senate was meant to check executive power; but second—and equally important—it was meant to hover above the populist rabble, or, in James Madison’s words, “to protect the people against the transient impressions into which they themselves might be led.” Let the House members be ambassadors of those transient impressions; the Senate’s job was to provide intellectual stability and continuity. That’s why the minimum age of a senator is older than that of a House member (30 versus 25), and one of the reasons the Senate is so much smaller: to guard against “intemperate and pernicious resolutions” of “factious leaders.” That’s why only one third of the Senate is up for reelection at a time, and why senators’ terms are longer than the president’s: to protect against “mutable policy,” to “hold their offices for a term sufficient to insure their independency.”

But if you look at the Senate of today, all of those structural differences pretty much amount to nothing. The Senate has capitulated entirely to popular sentiment, or (in Madison’s words again) “popular fluctuations.” Just look at that tea-party-inspired amendment spree, or the senators’ repeated declarations that health-care reform ought not to pass because polls showed that people were against it. The institution is plenty “factious” and “intemperate”: A number of Democrats I spoke to noted that they couldn’t remember a single Republican on the floor when Tom Daschle, the former Senate majority leader, made his farewell speech, in 2004. And those six-year terms aren’t exactly providing much intellectual stability. How could they, when a contentious Senate race—Daschle’s, for instance—can cost upwards of $20 million, forcing senators to chase money hour to hour, month to month, year to year?

The Senate, in short, has become another House of Representatives. In fact, almost half of today’s Senate—49 percent—is made up of former House members (as opposed to 1993, say, when the number was 34). During health-care week, it was the House that tuned out the polls and the Senate that went into partisan overdrive—pouring forth talk-radio cant, shutting down government (right out of Newt’s playbook), and pinning as many amendments onto this donkey as was legislatively possible, all in an effort to beat back a bill that, like a common bill in the House, required just a bare majority vote.

This is a potential recipe for pandemonium. The same Senate rules that were designed to check populist passions can, when adopted by passionate populists, turn the place into a governing body of 100 autocrats. Today, the four GOP senators most renowned for holding up legislation—DeMint, Coburn, David Vitter, and Jim Bunning—all came from the House. Its folkways are very different. Members in the dominant party don’t have to reach across the aisle to pass legislation, because a simple majority can steamroll the opposition. The place is so big members seldom bother to get to know everyone. Toward the end of his career, Alan Simpson, the retired Republican senator from Wyoming with a renowned penchant for pungent epithets, remembers some of the freshman senators, former House members, being stunned when he mentioned that he’d had conversations with Ted Kennedy. “They’d say, ‘You talk to him?’ ” he says. “And I’d say, ‘I work with him. He’s never broken his word.’ And they’d look at me like I’d gone commie.”

Photograph by Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

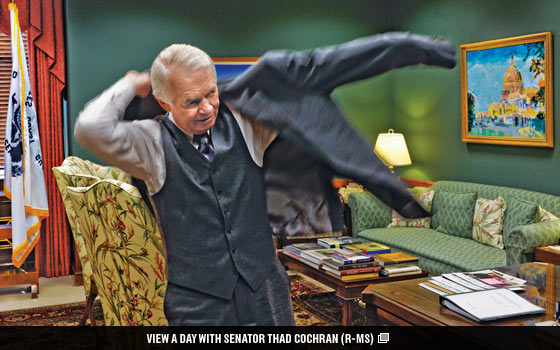

It’s worth examining how we got here. Forget about the fact that Congress has received consistently low approval ratings over the last few decades. (Harry Reid’s approval rating has actually gone down six points since January, from 35 to 29, in spite of the health-care victory.) The real problem is how much senators themselves have soured on the institution. The most searing testimony on this subject has lately come from Evan Bayh, who announced his retirement in February. But he’s hardly the only one. Most old-timers will tell you that the job’s more demanding now, and that its psychological pleasures are fewer and farther between. “I think there’s still a source of pride in being in the Senate,” says Thad Cochran, a genteel, no-nonsense Mississippi Republican who’s been in office since the Carter administration. “But new senators might not enjoy their service as much.”

At its crudest level, this senatorial malaise has to do with the concept of “hurry sickness,” or the sense that we’re inexpressibly busy, never able to unplug ourselves from the grid. Most professionals suffer from hurry sickness to some extent. But it is hard to think of a group that suffers from it more than senators, whose time is seen as a public commodity. “People expect more than you can deliver now,” says Cochran. “It’s harder to attend all the events you’re expected to. More people come to see you in Washington; you have all the organized professions and groups, and they’ve all got volunteers who get emotionally involved and let you know what they think … ” I ask what the most frustrating aspect is of his life today. He thinks. “Not being able to be everything to everybody,” he finally says. “You have to make choices on controversial issues, and there’s nowhere to hide.”

Theoretically, the framers wanted senators to live and think in an unhurried, unobstructed way. And one of the reasons that Cochran can speak so candidly about these matters, no doubt, is that he’s one of the rare unhurried senators. Jon Tester, a Montana Democrat who still runs his own 1,800-acre farm, comes off the same way, and his explanation for it is simple: no cell service. “When I’m on the farm,” he says, “I’m on the tractor, alone. You can think through all kinds of stuff with a motor humming in your ear.” But for the most part, if you approach a senator these days, you are greeted by a look of mild terror before the practiced smile kicks in: Dear God, not now. “There’s just an incredible intensity to Senate life,” says Daschle, now a senior policy adviser at the law firm of DLA Piper. “You have to vote, you have hearings, you have markups, you have your five minutes of questions at committee meetings, you have speeches to give, you have home-state problems and constituents demanding to see you, you’ve got press and press-related things. And all of that is happening simultaneously. And then,” he adds, “you’ve got to fund-raise.”

“You’re now a demagogue the full six years,”says Bob Bennett, whose father was also a senator.

One can’t understand the dysfunction of the contemporary Senate, stresses Daschle, without understanding the deranged state of American political fund-raising. It’s a massive, Sisyphean distraction, a slog into which senators pour thousands of hours that could be spent reading, negotiating, or talking to constituents. And some of this time-consuming process has been the direct result of various campaign-finance reforms themselves. Lawmakers can’t make fund-raising phone calls from their Senate offices, for example, “which means you have to uproot yourself, go to your political office, go vote, and then go dial for more dollars again,” says Daschle. “That’s almost a daily occurrence.” He estimates that today’s lawmakers spend at least 10 percent of their time fund-raising. As their elections draw near, he says, the number climbs to 40.

“I think the problem is that we’ve lost the capacity to actually legislate,” says Olympia Snowe, the moderate Maine Republican who worked with three Democrats and two other Republicans—“the Gang of Six,” as they came to be called—to fashion a bi-partisan health-care bill. “Nor is there any patience to allow the process to take hold.” She rattles off the usual explanations for why this may be—exaggerated partisanship, the generally anxious tenor of our era. But then she, too, mentions the time crunch. “People don’t have time to sit still for one moment,” she says. “I’ve spent weekends, late weeknights, until midnight trying to get the right approach to this issue. My last year and a half has been consumed by health care. But the point is, no one has time.”

It didn’t help, she adds, that she and her five compatriots were working in a media universe that compressed time, where “everything is telegraphed within nanoseconds.” This obsession with process inevitably led to less patience with it. “There was a lot of criticism about how much time we were taking,” she says, “which to me was an indication people didn’t understand the complexities of health care, which warrant that much time.”

As she’s speaking, I realize something about the Gang of Six. They came from Maine, Wyoming, Idaho, Montana, North Dakota, and New Mexico—all states with tiny populations. They probably have a better sense of retail politics, an instinct for the hands-on, gritty business of building consensus and getting things done. But more important, senators from small states generally spend less time fund-raising, which means they may even have time, as Snowe would say, to “actually legislate.”

The common rap on the Senate is that it’s a club. And once upon a time, that was certainly true, and some of the reasons for it were ugly. As Sherrod Brown, a Democrat from Ohio, notes: “Old-timers say there was more comity back in their day. Well, yeah, because there were a lot more white guys running everything together.”

But truth be told, the Senate would function a hell of a lot better if it were a club—not in terms of exclusivity, of course, but sensibility. Clubs generate their own morale and sense of fealty. In the words of Patrick Leahy, a Vermont Democrat who’s now the third-longest-serving senator in the body, more people from his generational cohort “put the Senate first.”

The metaphor for today’s Senate isn’t a club, but an airport lounge. This isn’t only because senators are overscheduled. It’s because so few of them enter the institution with plans to spend a lifetime there. With an insatiable family of 24-hour news networks following their every move, new politicians now use the Senate as a launching pad for a higher form of celebrity—often the presidency—rather than view it as a place to master the art of policy-making and die with their boots on. (Think of the three main Democratic presidential contenders in 2008: Barack Obama, Hillary Clinton, and John Edwards had each barely been in the Senate before declaring their candidacies.)

The prestige of the Senate has also eroded. This may in part be the effect of C-Span and other forms of transparency, which have demystified the place. It may in part be a reflection of the times: Few of us stay in the same jobs our whole lives, even senators. (Tester, for instance, told me he’s always planned to return to his farm, and it’ll be much easier now: “Before I had this job, I couldn’t afford health care.”) But it’s also because of the giant wave of Republicans elected to Congress in 1994, who came of age during the Reagan era, believing government was the problem. They ran on a platform of term limits, which implicitly denigrated the value of public service, and they made a fetish of returning each weekend to their home states and not keeping their families in D.C. Now all senators are expected to lead a peripatetic life, despite the exhausting commutes this may require.

Consider Democrat Ron Wyden, who in a recent interview mentioned five town meetings he’d held in the eastern part of Oregon, all in one weekend. To make it back to D.C. on time, he had to drive from Hermiston, Oregon, to Pasco, Washington, and then take a small plane to Seattle in order to catch a red-eye to Dulles Airport. Now, no doubt the trip was valuable. But Wyden’s also an old-fashioned legislator, which by definition requires intensive interaction with colleagues. Three years ago, he and Bennett introduced a serious bi-partisan bill to reform health care; just a few weeks ago, he and Gregg introduced a tax-reform measure. These efforts require a certain level of comfort with colleagues. How can you develop that comfort if you’re never around?

“It’s much easier to write a bi-partisan bill with a friend,” says Pete Domenici, the retired Republican senator from New Mexico. “The problem is that it’s harder to develop friendly, lasting relationships in the Senate today.”

Much of today’s Senate is new—one third of the Democrats were elected or appointed in the last two cycles, for instance—which means that close relationships are bound to be rarer. But most veterans of the institution say the contemporary Senate conspires against them. Senators almost never have one another over to their homes anymore. The Senate dining room is usually empty, because members are triple-scheduled with meetings during lunchtime and fund-raisers at night. “And that really is a shame,” says Leahy, who remembers the days when senators would reach over one another to taste each other’s food. “Even if you’d been fighting like mad on the floor an hour before, you’d suddenly remember, ‘Say, your kid applied to Dartmouth—did he ever get in?’ ” Before the advent of C-Span, the Senate floor used to be a place where lawmakers mingled and engaged in genuine debate, and junior senators would race to get there, simply for the sake of hearing an eloquent speech. “Like Russell Long—he would occasionally have a drink before he made one,” says Cochran. “His voice would rise about an octave over normal, and you’d think, Oh, Russell’s getting wound up now.” He marvels at this idea for a moment. “People sat and really listened to someone like that. It was part of your Senate education.” Then he’s silent. We’re on the phone, and I realize he’s looking at his television set. “Of course, there’s no one on the floor now.”

Nor can one imagine senators sitting around having cocktails with one another today, at least openly, which is also a shame. Democracy worked a lot better when senators drank and smoked. Into the eighties, the secretary of the Senate kept an open bar for lawmakers who were milling around after hours, waiting for votes. As a young senator, Leahy was asked to bartend for his senior peers. “I remember sitting in Mike Mansfield’s back room”—Mansfield was the Democratic leader during the civil-rights era—“and suddenly I hear hrrrrrrrr. And I look over, and there’s Jim Eastland with his empty glass, glaring at me.” James Eastland, a white supremacist with a committee gavel, was a Chivas Regal man. “There were some wonderful discussions then,” adds Leahy. “You’d get Hubert Humphrey and Barry Goldwater telling stories. Mansfield would sort of puff his pipe. And then he’d say, ‘You know, boys, I’d like to wrap this up. Do you suppose that if you brought up your amendment, and then you brought up yours, we could pass the bill and go home?’ And they’d say, ‘Good idea!’ ”

All of us can say good riddance to the likes of Jim Eastland. But it’s kind of sad that we’ve had to bid the same to Chivas Regal—and backroom deals, frankly, which, for all their unsavory secrecy, seem like a palatable bi-partisan alternative to the transparent partisan gridlock we have today. The closest version we have to them now, true to the times, are alliances formed in the senators-only gym. “Ted Kennedy and I had some of our best discussions in the gym,” says Richard Burr, one of the Senate’s most conservative members. He smiles. “Though you’d look at Ted, and you wouldn’t necessary know … ”

So, I say, you guys talked on the treadmill?

He stares at me. “Ted didn’t always find his way to the treadmill. But I don’t think I could have passed the biodefense legislation with him if he and I hadn’t come to an agreement when staff wasn’t around.”

If one were to compare the America of today with the America of, say, the sixties, there’s no question which was more bitterly divided. Bob Dove, who became the Senate’s parliamentarian, remembers when George McGovern proposed an amendment to cut off funding for the Vietnam War, famously proclaiming that the Senate chamber reeked of blood. “There was a chilling reaction to that speech,” says Dove. “I haven’t seen anything like it since.” Indeed, our differences as a nation have grown smaller. It’s the differences between the two parties that have grown greater. And that, more than any of the other routine explanations—Fox News, Karl Rove, the primary system—explains why our government is more partisan today than it has been in decades.

“We’ve lost the capacity to actually legislate,”says Olympia Snowe. “No one has time.”

The best way to explain this change is to look at the passage of the Civil Rights Act. Back then, there was a “four-party Senate”—northern Democrats, southern Democrats, liberal Republicans (from the Northeast, mainly), and conservative Republicans (from the Midwest and West). Southern Democrats were conservatives and often straight-up racists, invested in upholding the structures of the old South. Northern Democrats wanted to dismantle them, as did liberal Republicans. And while some conservative Republicans opposed the Civil Rights Act, they did so less out of racist anxieties than principles of limited government. But the point was this: There was seldom such a thing as party unity. When LBJ wanted to pass the Civil Rights Act, he leaned just as heavily on the Republican leader, Everett Dirksen, as he did on Mansfield. And in the end, Dirksen delivered a greater percentage of his caucus—27 out of 33 senators, versus Mansfield’s 46 out of 67. (Marty Gold, the former adviser to Howard Baker, likes to remind people that Richard Nixon got 32 percent of the black vote in 1960.)

“When I was first elected to the Senate in 1972, the Democrats were a different species of cats,” says Domenici. “The southern Democrats were more like Republicans—and the northern Democrats couldn’t kick them out, because they were chairmen, they ran the place!” He looks over at an aide. “Like who was the Judiciary chairman when I came in? Big bushy eyebrows … ” He thinks. “Eastland!” With his fondness for Chivas Regal. “Cigars, scotch, southern as a mushroom.” He smiles. “So the Democrats and the Republicans weren’t natural enemies then. And filibusters weren’t for partisan reasons.”

As LBJ himself predicted, the vote on the Civil Rights Act triggered a realignment in American politics, almost entirely ridding the Democratic party of Southerners. From the late sixties onward, they either switched parties or retired, with Republicans filing in in their stead, while liberal Republicans slowly found themselves replaced by Democrats. A few moderates would remain in each party (today, the Democrats have the lion’s share, which explains why they’re the more unwieldy bunch). But by 1994, this realignment was nearly complete, with Republicans capturing not only the Senate but the House, which hadn’t been GOP-controlled for 40 years.

The purification of both parties had significant consequences. Congress was suddenly closely divided, and it would remain so, with the gavel always up for grabs. Partisan aggression became standard procedure to recapture or defend the majority—to the point that Bill Frist, the majority leader in 2004, flew to the home state of his counterpart, Daschle, to campaign against him during a tough election year. (“That helped legitimize a policy of ‘anything goes,’ ” says Chuck Hagel, the retired Nebraska moderate. “I remember saying to Bill, ‘How do you think you two can sit down on Monday morning and go through an agenda when the element of trust is gone?’ ”) Senators were suddenly rewarded for their partisanship, both with special-interest-group money (polarizing figures are great for fund-raising) and air time (ditto for ratings). And party unity emerged as a transcendent, overriding value, particularly for Republicans, whose cohesion seemed to be reinforced from the top down. Lincoln Chafee, the liberal Republican from Rhode Island, who lost in 2006, says he couldn’t understand why the old-timers went along with it—especially during the Bush years, when the president kept proposing measures far beyond the Treasury’s means. “It’s a mystery,” he says. “Ted Stevens was a pilot in World War II. He’s a brave man. Why didn’t he and John Warner and Pete Domenici and Chuck Grassley and Richard Lugar go down to the White House and say, ‘You don’t have us on this’? I’d ask, and they’d always say, ‘The president wants it.’ ”

Cass Sunstein, the Harvard legal scholar and Obama-administration official, has a theory about this: that people become more radicalized when they spend too much time in like-minded company. And maybe that explains some of the mystery Chafee is describing. Starting in the eighties, both parties began having weekly policy lunches. Eventually, they turned into pep rallies and partisan breeding grounds. For centrists or party outliers, they could be uncomfortable places to be.

“It was painful at times,” says Chafee, who’s now running for Rhode Island governor as an Independent. “Even my health improved after leaving the Senate. I had health issues that instantly went away.”

Like what?

“They were stress-related,” he said. “Let’s just say I had to make sure I chewed my food very carefully in the Senate.”

Don Ritchie, the Senate historian, likes to point out that the Senate was never meant to be a parliament, with its members consistently voting along party lines. But that’s what’s happened. And when Obama came in, ushering in a Democratic supermajority in the Senate, he got to play the role, however briefly, of a prime minister. “Until Scott Brown,” McCain says, “there was no bi-partisanship. They figured, ram it through, pick up a couple of Republican votes along the way, or maybe not. But I know bi-partisanship when I see it. And that’s not bi-partisanship.”

Snowe puts it a little more generously. “I said to the president, ‘The good news is you have 60 votes, and that’s the bad news, too.’ ”

To those beyond Washington, Snowe’s decision not to vote for the final health-care bill may have seemed puzzling. It did not, after all, have a public option, the most publicized sticking point for many Republicans. But that’s not how it looked to those who watched Snowe at close range. She worked with Democrats for months, and she was the only Republican to vote for the health-care bill when it left the Finance Committee. But Harry Reid offered a far more liberal version of the bill on the Senate floor. He knew Snowe probably wouldn’t agree to it. “I think they recognized they had 60 votes, and that empowered them to concentrate on the members of their caucus, rather than make specific policy concessions to a Republican,” she says. “So it ended there.”

Obama ran on a platform of transformation, saying he’d effect huge changes both in policy and partisan culture. But it’s possible that you can’t have both.

Before the health-care vote, Wyden had had his low moments during this Congress. “Right before all the snow fell,” he says, “I remember I felt like everything had gotten so distorted—I’d listen to constituents and realize they couldn’t make hide nor hair of the health-care bill.” On those dispirited occasions, he did what any former college-basketball player would do: put on his jeans, left the Senate, and walked to a nearby playground to shoot hoops. Now, he’s obviously elated. But not deluded. “Let’s just state the obvious,” he told me on the day of the reconciliation vote. “The climate after health care will be more challenging.” Yet he pointed out that in the middle of all the partisan stagecraft, he and Gregg are still working on their bi-partisan tax bill. Snowe is working on a bill with Jay Rockefeller about cybersecurity. (It passed in the Commerce Committee the first day of Vote-o-Rama.) People are still managing to find areas of agreement. Maybe not on climate change or immigration. But tax policy and cybersecurity are hardly trivial. And Wall Street reform has a decent shot. “I still think ideas-driven politics has a place,” says Wyden, “as tough and exasperating as this is.”

And in fact, something interesting was happening on that final day of Vote-o-Rama: Senators were finally, at long last, interacting with each other. It’s been a long time since they’ve all been down there at once, spending so much time on the floor. And suddenly, they were listening to one another, as banal as their speeches often were. When the chamber got too loud, senators would call for order so that their colleagues could be heard; when the final roll was called, Harry Reid was so distracted by the proceedings that he initially voted “no”—the second time he’d made such a mistake—and set off a ripplet of laughter.

“Last night was one of the most cordial evenings I’ve had here in a long time,” said Coburn the next morning. “I talked with Sheldon Whitehouse, Al Franken,” both Democrats. “I spent 30 minutes visiting with Harry Reid!” (Who’ll have to spend the fall accounting for his vote on Coburn’s Viagra amendment, no doubt.) Even the ludicrous amendment spree, some of his colleagues were saying, had its value, as a perverse form of sport. At the very least, they were arguing face-to-face, rather than through press releases and talk radio. “I enjoy the fight,” McCain confessed to me. “Ted Kennedy and I used to enjoy the fight. We’d go nose to nose, but there were other things we’d agree on. Ever see Ted Kennedy fight?” I told him I had. He’d work himself into high dudgeon, then smile at his foes once the cameras were off him. “Well, yeah,” said McCain. “We believed that a fight not joined was a fight not enjoyed.” It may be the preferred mode of nursery-school children. But at least they weren’t sitting at home.

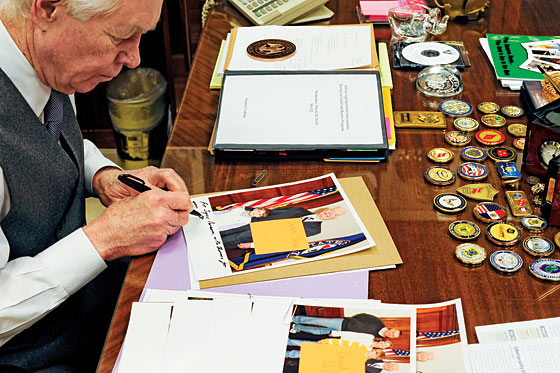

A Day With Senator Thad Cochran (R-MS) 9:14 A.M.: A meeting of the Defense Appropriations subcommittee. Photographs by Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

11:35 A.M.: Leaving his office in the Dirksen Building.

1:05 P.M.: Meeting with representatives from the University of Mississippi.

A Day With Senator Ron Wyden (D-OR) 1:31 P.M.: Discussing the health-care bill. Photographs by Peter van Agtmael/Magnum Photos

3:04 P.M.: On the train between the Dirksen Building and the Capitol.

4:26 P.M.: On the phone in his office.