On the evening of September 19, 1977, a few hours after being dealt a humiliating defeat by Ed Koch in his bid to become mayor of New York, Mario Cuomo held a quiet conversation with his oldest son, Andrew, and his wife, Matilda, in their home in Holliswood, Queens. Mario was by then a crusading lawyer with a reputation for eloquence and passionate social commitment, already on his way to becoming a kind of philosopher-statesman. Yet as a politician, he seemed destined to be a footnote—“a loser,” as one political observer later said. Andrew refused to accept that fate for his father. The son was a tough, competitive, smart, though not terribly bookish, young man, with a Queens accent so pronounced that some thought it an affectation. He had a kind of blue-collar spirit—he was good with his hands and had toyed with opening a gas station. Until his father’s defeat, Andrew hadn’t seriously contemplated a career in politics. But that day he turned to his mother. “We’ll make Dad a winner,” he told her sharply. He was 19 at the time.

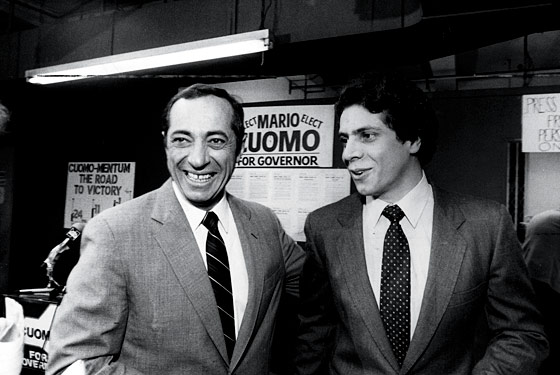

Mario rode Hugh Carey’s coattails to victory as lieutenant governor the next year, a consolation prize. And then, in 1982, with the fierce, sometimes vindictive style that has characterized his elective efforts ever since, Andrew masterminded his father’s come-from-behind victory for governor against Koch, among others, after Mario had trailed in the polls by as much as 38 points. “Sure enough,” Mario told me, “Andrew made me a winner.” The victory changed both of their lives. It launched Mario into political stardom—he served three terms as governor—while it gave Andrew, who’s almost certain to win his father’s old job this November, an arrogance that would take two decades and humiliating defeats of his own to confront. “At 24, Andrew was given a belief he could control events,” says a friend. “It made him an asshole.”

Typically, the father passes the torch to the son. With the Cuomos, there’s a twist. Andrew, in some sense, grabbed the torch prematurely, the son having done what the father couldn’t do for himself. And Mario, now 78, hasn’t been eager to relinquish it—he hates being muzzled. The two are still obsessed with each other. They bicker good-naturedly over almost anything, from who beat whom at basketball (neither will admit to ever having lost) to their comparative political talents. And they each keep careful track of the other’s accomplishments—an internal scorecard that begins with the relative difficulties of their youths.

“My father was not physically around much,” Andrew tells me, then pauses, calculating his father’s response. “He’ll admit it, depending on the day.”

Mario was a workaholic before the term was popular. “I don’t think I realized it at the time. I don’t know that I still actually realize it,” Andrew says in his bland, spacious state attorney general’s office, which he’s occupied for the past three and a half years. “He was so focused on what he did. If you wanted to develop a relationship with him, you had to go where he was, because he wasn’t going to come to where you were.”

Andrew, 52, has his father’s dark hair and long face—Mario once described his own bags-under-the-eyes looks as those of “a tired frog.” Andrew is handsome in a film-noir way, though right now he’s dressed like a prosecutor in a dark suit and crisp white shirt with cuff links. He insists he doesn’t want to speak about his father, but can’t resist for long—it is, after all, the topic that makes him come alive.

“My father was running every few years,” he says. “I got involved in his campaigns because it’s what he was doing. I think it was a way of developing a relationship.”

Mario’s brutal work ethic was an inheritance from his immigrant father, who, as Mario has said, “bled from the soles of his feet” to provide for his children. Mario later mythologized his parents as American heroes (to considerable political effect), but the myth concealed a punishing truth. Andrew’s grandfather and namesake, Andrea, ran a small grocery store in South Jamaica, Queens, which he and his wife staffed 24 hours a day, a grueling schedule that left little time for Mario, their youngest son. Mario spent years working in the back of the store, where for amusement he turned boxes into toys and read—Dickens, among others. “I had no youth,” he told his biographer Robert S. McElvaine. “I remember a thousand days being alone in my own quiet world while all the neighborhood’s activity was going on, steps away, on the other side of the door.”

Mario told me that he’d never had a long talk with his father. Advice was given in simple syllables: “Puncha, puncha, puncha, fighta, fighta, fighta.” Andrea couldn’t read Mario’s report cards, but he knew when his son received a B instead of an A, which earned him a rap on the ears. Mario’s mother was cool and unemotional and provided little relief. “I won three damned governor’s races, and she never said a thing about them. She never said, ‘How nice.’ Never gave me a hug and a kiss,” Mario explained to me.

Mario’s difficult childhood was one of the family’s foundational stories—all the kids know it. “My father was literally born on the other side of the tracks,” Andrew says, then dissolves into a laugh. They’ve been through this argument dozens of times, and, for once, Andrew concedes. “The poor neighborhood is a more dramatic characterization,” he says—then with a note of defensiveness adds, “The middle class may be more representative [of voters today].” These days, candidate Cuomo is sensitive to the authenticity of his own urban roots. His Queens may have been middle class, but it “was real,” he tells me insistently. “It was real. It was real.” The Queens of Andrew’s memory—he moved out twenty years ago—is a place to which the candidate, now a Westchester resident, wants to appeal. “I know the kitchen table in Queens,” he says. “I know those people, their faces. I know where they’re coming from, what they’re dealing with, and that orientation to people, to values, work, honor, handshake, relationships,” ticking off the themes as if they need no explanation.

Mario was ostentatiously selfless, devoted to causes greater than himself, which often meant ignoring the needs of those closer to home, a fault for which he berated himself while not doing much about it. “I can’t blame Matilda for being angry at my refusal to make money,” Mario wrote in his published diaries, a copy of which sits on Andrew’s desk. “She doesn’t see it as a commendable effort … she sees it as selfishness on my part.” But the greater hardship was Mario’s absence. His old friend and law associate Fabian Palomino recalled for Mario’s biographer a conversation from 1975. Mario mentioned that Andrew was graduating from high school. How is Andrew doing? asked Palomino. “You know, I really don’t know,” Mario replied. “I haven’t spent a lot of time with him in the last four years. I guess I’ve taken him to two or three ball games. Matilda made me take him.”

Mario’s early childhood was that of an ethnic sealed off in his own enclave—he didn’t speak English until school—and it marked him with a deep sense of his own foreignness, a by-product of which was shame. As a young student, Mario hustled to keep his mother and father away from other parents at back-to-school days: “I didn’t want them to know that my parents didn’t speak English well.”

Mario worked ferociously, racking up achievements that were supposed to cure the self-hate syndrome, as he later called it. He tied for first in his law-school class, and yet the elite firms didn’t call. “Not one interview,” he told me, still fuming at what he viewed as an ethnic slight. The result, one of his old colleagues said, was that “Mario never felt he was entirely American.”

Andrew suffered few of the internal torments his father endured; he never doubted his place in the American mainstream, nor in Queens, which in his experience was active and fun. There was parochial school and work and girls. Partly to support his father’s higher calling, Andrew worked constantly, paying for college at Fordham and then Albany Law School. He cut lawns. He pumped gas. He’s a gifted mechanic. “If you were a member of the Triple A,” Andrew says, “I was the person who would show up.”

With Mario gone, Andrew assumed the role of man of the house. “He was my mother’s rock,” says his younger sister Maria Cuomo Cole, who married the fashion designer Kenneth Cole. “In many ways, he grew up too fast,” Matilda tells me. “He was a little man.” She recalls that he greeted Maria’s dates at the door, dispatching paternal duties solemnly, if not always convincingly—“He tried,” Maria says. With baby brother Christopher, thirteen years Andrew’s junior and the youngest of the five children, his efforts were more successful. “Andrew kind of raised me,” Chris tells me. It was Andrew who dropped Chris off at Yale, handed him a bunch of cash, and delivered a fatherly talk about not screwing up. Andrew is still the key authority figure for Chris, now 40 and a co-anchor of ABC’s 20/20. “One of the greatest pleasures in my life is that he depends on me to tell him what I think,” Chris says.

If Andrew and his siblings missed their father, they didn’t dare blame him. “We knew he was doing important work,” says Maria. When he was home, Mario often led conversations on societal ills, and could be fun, though for Andrew’s father, a deeply religious Catholic, joy hovered just out of reach. “Old-fashioned Catholic guilt is the absolute best. It ruins everything,” Mario told McElvaine. For Mario, the only salvation was good works, which were to be undertaken with devotion, and a kind of hopelessness that they’d bring earthly satisfaction. In the Cuomo household, public service was the only route to respect, and the family heeded the call. Maria leads HELP USA, a low-income-housing organization that Andrew founded, and Matilda, at 78, helps lead Mentoring USA, an organization she started that provides guidance and tutoring for the underprivileged.

It wasn’t always easy to measure up to Mario’s expectations. Chris spent three years as news anchor of ABC’s Good Morning America, a coveted job greeted with ambivalence at home. “My father struggled with it as a significant form of service,” Chris tells me. (Andrew echoed the sentiment: “You got to decide what’s more important: your personal celebrity or what you’re able to do for other people,” Chris recalls him saying.)

By the time Mario was in his forties, the Cuomo family business was politics, and Andrew was absorbing the lessons, one of which is that ideological purity isn’t always the best political strategy, no matter what his father might say. “My first remembrance of him in politics is his position on the death penalty,” Andrew tells me. Mario opposed the death penalty, perhaps his defining issue. Pollster “Pat Caddell, who at that time was the big guru, said, ‘You cannot win [for governor in 1982] with that position, but the good news is you’re not on record anywhere, so you can change it.’ My father said, ‘I’m not changing it.’ Caddell said, ‘Okay, well, at least never bring it up.’ So my father would go out on the stump, and if someone asked, ‘What do you think about the transit fare?’ he would say, ‘I’m glad you brought up the death penalty.’ ” Andrew shakes his head and laughs warmly: “His politics are, You say what you believe. Whatever happens happens. He’s not a replicable model.”

When Mario served as lieutenant governor, he decided to live part-time with his son, then at law school in Albany. I asked Mario if he roomed with Andrew for the fun of being together, which is how that time is often characterized. He seemed surprised by the question. “Our family couldn’t afford to do a lot of things for fun,” he said. The lieutenant governor had to provide his own housing; sharing an apartment was a way to save money. For Andrew, his father’s motives were simpler still. “He was just trying to slow down my bedroom activity,” he says. (Mario, a virgin when he married, hung a Virgin Mary in the apartment.)

The turning point in Mario’s political career—and the crucible of his relationship with Andrew—came during the 1982 race for governor. “It’s difficult for a young son working for a father,” Andrew says, but in the midst of the battle, they found that they were complements. Mario pondered the big questions while rising early to record his personal flaws in his diary. “If you said to my father, ‘Design your perfect day and your perfect job,’ ” Andrew tells me, “intellectual ideas, thoughts, reading, writing, communicating ideas.” Andrew staked out territory his intellectually domineering father couldn’t or wouldn’t enter. “I like to think I think the big thoughts,” says Andrew, “but I also operationalize.” Andrew means that he turns ideas into action. Put another way, he gets the job done. “Andrew would do what works; Mario, he would believe it works,” says a political associate of the Cuomos. It was in Mario’s service that Andrew first nurtured the idea that most anything is justified for a good cause—like his father’s career. “It went beyond what a dedicated political supporter would give to a candidate,” says a former political colleague. Back then, Andrew was sometimes called the Prince of Darkness, a political wizard who “threatened [party members] with the loss of lucrative state jobs” to get his way, as a state report concluded.

To some, Andrew appeared to have a chip on his shoulder, as though every attack were personal, a perception magnified by his youth. “He operated from anger in those days,” says the former colleague. “It was as if Andrew was Mario’s id. They were both supersensitive to any criticism. Anything would set them off.” With Andrew, every infraction mattered, even those committed by loyalists. “Andrew gave [one county official] the scorched-earth treatment” if he didn’t fall in line, says one former elected official. “He said to me, ‘I’m on the team. Why is this happening?’ ”

Mario bestowed power on Andrew, or allowed him to take it, a sign of his love and faith, but it proved a mixed blessing. Andrew doesn’t share Mario’s brooding nature, which tempered his father’s aggression. He knows he lacked “emotional maturity” at the time. “He had an enormous amount of power and not the temperament to wield it,” says a friend. “It wasn’t fair of his father to put him in that position.” Fair or not, Andrew was seen as his father’s henchman, a thug, a paternal legacy that, though Mario rejects the characterization, persists to this day.

For father and son, the 1982 campaign created a primal bond, one that had been absent at home. “I was thinking about this the other day,” Andrew says. “[The campaign] was an emotional, personal relationship on every level—it’s not like he was an accountant. I’ve been with him on his good days and on his worst days. It’s a much fuller, richer relationship.”

Of course, Mario is an unforgiving competitor. “Good thing we won,” says Andrew with a thumping laugh. “If we’d lost, it would have really been bad.”

After the campaign, Andrew was a new person—one with a greatly expanded reputation and barely contained ambitions, as well as a list of enemies. But the son still lived in the father’s shadow, and through his twenties felt a need to insist, as he told one journalist, “I am Andrew Cuomo, and I am an independent person.” Even then, Andrew longed to run for office, but, he’d quickly add, only when his father was gone.

By 1985, Andrew had struck out on his own, briefly joining the Manhattan D.A.’s office, then a Park Avenue law firm. As the son of a sitting governor, he wielded enormous influence, and reveled in it, and yet as the son of Mario Cuomo, he wasn’t supposed to enjoy the privilege. “He’s psychologically empowered,” explains a friend. “It inflates the ego, and, of course, he feels, I deserve this power. But as a Cuomo, you have to figure out, How do I not feel entitled?” In 1986, Andrew retooled his father’s ideals, and put his expansive ego in the service of his own good works. He founded HELP USA, a private-public partnership that only someone as strong-willed, clever, and connected as Andrew could have pulled together. “He really changed the way the city and country care for homeless people,” says a former colleague. It also turned out to be a brilliant career move, which, along with his pedigree, quickly yielded results. In 1993, Housing and Urban Development secretary Henry Cisneros chose Andrew as an assistant secretary. When Cisneros departed in scandal three years later, Andrew knew he was the best person for the job and wasn’t about to let anyone stand in the way of his good intentions. Norman Rice, then the mayor of Seattle, was another contender for the post, but his candidacy stalled after reports about an investigation that Rice misspent HUD money, an investigation approved by Assistant Secretary Cuomo’s department. The charges proved baseless, but by then it was too late for Rice. In 1997, the Senate approved Andrew as HUD secretary—at 39 years old, the youngest Cabinet member in history, as he has sometimes noted (though in fact it’s Robert F. Kennedy, his ex-father-in-law, who holds that distinction). By most accounts, he did an excellent job expanding the mission of an agency so ineffective and corrupt that it had been in imminent danger of being shut down.

As a Cabinet secretary, Andrew not only did good but also felt he’d arrived—above a mere governor, which he didn’t mind pointing out to his father. Andrew recalls a meeting at which Vice-President Al Gore, Andrew’s friend, mentioned that in protocol, a HUD secretary is more important than a governor—thirteenth in line to the presidency. Mario was in the audience. “I don’t know if Mario had fun with it, but I did,” Andrew says.

Playgirl had once named Andrew one of the country’s ten most eligible bachelors, but before he arrived in Washington, he gave up the title and married Robert Kennedy’s daughter Kerry—characteristically mixing life and politics. The press called it a merger or a ticket, and it was impossible to look past the union’s professional advantages. Still, the couple did have a lot in common—Kerry founded the RFK Center for Human Rights. “Just look at the two of them, their values and their priorities are so much the same,” Matilda Cuomo said at the time. “You just know this marriage will last a lifetime.”

The June 9, 1990, wedding was the political affair of the year, so overbooked that Andrew had to disinvite a friend or two from the old days. The press noted the elevation of Andy from Queens, as he was once called, though by then the Kennedys’ reign as political royals was mostly over.

For their part, some of the Kennedys were not taken with the Queens mystique. Andrew didn’t always dress quite right—too fond of cuff links, perhaps. And then there were his manners. At the Kennedy-family compound in Hyannisport, a person is supposed to toss a football, go for a swim, and, come dinnertime, argue passionately about the national good. “Andrew refused to do anything fun, anything without a clear benefit to his career,” a person who’s spent time with the family reported.

While Andrew was off at HUD, Mario’s political career went into eclipse. The governor dithered while opportunities passed him by: a run for the presidency, a nomination to the Supreme Court. In 1994, he mounted a dutiful campaign for a fourth term—he insists he would happily have bowed out if he’d found another candidate against the death penalty. Andrew had tried to talk his father out of the race; he knew the public was tired of the Cuomo name. And from Washington, Andrew couldn’t help with the campaign, a crucial point in Andrew’s mind. “I was not involved in any serious way with an election he lost,” he says. “He”—Mario—“has noted that.” In 1994, the great man fell at last, losing by just four points, a margin some attributed to his death-penalty stance, to a relative unknown from Peekskill named George Pataki. It was a deep sadness for Andrew, but also, at last, an opening.

In 2001, a week after leaving HUD, Andrew marched into New York like a returning hero to declare his own bid for governor against Pataki. Kerry accompanied Andrew on the campaign trail, spreading the Kennedy fairy dust. Still, in that campaign, it was the Cuomo name that mattered. “There was a whole crosscurrent,” Andrew says, “of the party not wanting to go back to another Cuomo.” Andrew may have been a stronger general-election candidate, but party leaders had already rallied around the likable state comptroller Carl McCall, who’d apparently reserved his spot in line.

In his office, I ask Andrew how he made what is, in retrospect, an obvious political blunder. He pushes back in his chair, moves his hands around like he’s about to pass a basketball. “I don’t know. I was going to go home to New York, and they were going to appreciate that. I had been part of the Clinton administration,” he says. “It’s not like I was on the beach in the south of France.”

Andrew’s campaign faced another challenge. He’s sharp-minded, naturally engaging, funny, and seductively candid, especially in small groups. In some old friends, he inspires an almost fawning loyalty—“He’s the person you’d want in a lifeboat,” one tells me. On the stump, Andrew showed passion, the type supporters said harkened back to his father-in-law. But to many, Andrew seemed to be trying too hard. “The more voters saw of him, the less they liked him,” explained one political observer. To some voters his expertise played as disdain, and even his passion seemed tinged with anger. Andrew, then 44, pulled out the week before the primary.

Andrew had long held an unshakable belief in his own destiny and hadn’t seemed to consider that he might fail. “I lose and my political career was over,” Andrew tells me. “I’m relatively young. I didn’t have a second career ready. No plan B.”

“My father liked the concept of people,” Andrew says. “I like people.”

Then came another, more humiliating blow. Nine months after his defeat, Kerry’s lawyer released a brief statement to the New York Times: Their marriage was over. Andrew acted as if blindsided by the announcement. The Kennedys, well schooled in public scandal, had expected Andrew to behave “honorably,” a Kennedy word. But Andrew’s pride was wounded, and his instinct to fight, never far from the surface, apparently took over. His own statement used the word “betrayed”—Kerry was seeing someone. (“She’s obsessed with him,” Andrew told a friend at the time, referring to Bruce Colley, her married lover. The friend added, “And he couldn’t get her away from him.”) Andrew’s statement infuriated the Kennedys. And not just for airing the seamier details in public. He was up to his dirty tricks, as they saw it, managing perceptions and distorting the truth. As a person briefed on the family version tells it, “Kerry had been trying for years to get a divorce.” She’d hired a lawyer, sent him letters. Andrew was trying to save the marriage. “You do everything you can to preserve a family, a marriage,” Andrew tells me. But for Kerry, the marriage had been over for some time. Andrew was inattentive, at best, and she’d begun to feel like his career accessory. In Kerry’s mind, if not in Andrew’s, they came to an agreement. “He begged her to stay with him through the gubernatorial campaign, with the promise that he would give her a divorce after,” says a family friend. Kerry believed Andrew would be a good governor. “She stuck with him during the governor’s race and asked him to keep his word afterward, and he refused,” still hoping to work things out.

In his sprawling office, Andrew asks me, “Did you read about the divorce?”

Andrew, a gifted narrator of his own life, says, “You are going to run for your father’s old job. You’re going to lose in a very terrible, tragic sense, and then your personal life is going to fall apart. That pretty much sums up a lot of fears I had at that time.”

It was a spectacular flameout, and for Andrew an unprecedented one. “I had had minor setbacks; I had not been hit by a truck and then the truck backed up over me.”

Andrew disappeared. He used to call up friends, family, associates constantly, sometimes just to check in. “How am I doing?” he’d ask. Now the phone went silent. Eventually, he taught at Harvard and edited a book on American politics, resurfacing in a one-bedroom apartment in downtown Manhattan.

Andrew didn’t discuss the divorce much with friends, not even with his oldest confidant—what would Mario know about divorce? Internally, however, there was a process going on. Andrew is into personal development, “self-improvement,” Chris tells me. (“I think Chris needs a lot of improvement,” quips Andrew when I bring it up.) Andrew tells me, “It was a terrible time in life. Yeah, all right. But the flip side is, the optimistic side: What can we learn from it? How do I improve?”

Andrew is a child of his time, more New Agey than his ascetically inclined father. He’s dipped into the seeker’s syllabus, reading The Alchemist, by Paulo Coelho, an achiever’s guide to the spiritual journey that urges each person to seek his “personal legend,” that which he wants most (and which, Coelho says, the world will help him find). For Mario, gloom is a steady state. You make efforts, but don’t expect answers. “Andrew is a positive thinker,” Matilda tells me. “He doesn’t dwell on the negative. He never did.” Yet if Andrew thirsted for inner knowledge, it was in answer to specific career questions. “Should I have run? How did I run the campaign?” he asked himself.

I ask if it was mostly hubris that did him in. “It was just a fundamental miscalculation,” he insists. “I forgot all politics are local.”

But Andrew seems to have learned another lesson. Even those closest to him could find him overbearing and obsessively controlling. Quietly, a few cheered his humiliation. “Andrew needed to be knocked down,” says a friend; “2002 was the best thing that could have happened to him. You have to learn by being humbled.”

Andrew had had a long love affair with his own destiny, and that was over for the moment. “The humiliation freed Andrew to be himself,” one friend claims. He listened to friends more, and spent more time with his three daughters, a comfort that he found a blessing and a bit of a surprise. “My father would be amazed at how much time I spend with my kids,” he tells me, as if noting a transgression. And Andrew’s outlook changed, his natural optimism suddenly tempered by a bit of Mario’s fatalism, if not his grimness. “There are things in life you don’t control,” Andrew says, working himself up. “Control is an illusion. You control nothing. Give up the illusion.” And yet, if humiliation caused Andrew to pause and reorient, Andrew is Andrew, pragmatic and unflinching. Laid low, he quickly found new reasons to believe in himself. “When you survive your worst fears, it’s actually liberating,” he says. “If you take a punch, will you get up? You always wonder. ‘Yeah, I think I would.’ But you don’t really know.” Andrew got up, with the counsel of his oldest ally. “Andrew never allowed [the 2002] loss to kill his desire in politics. Not for a minute,” Mario explains to me. “I’m not sure I could get up off the canvas,” Mario told his son, “but if you can and you make it, that would be an extraordinary accomplishment for you.”

Andrew surveyed the political landscape in 2005. Eliot Spitzer, the celebrated sitting attorney general, looked certain to win the governorship, leaving his office available. Andrew entered the race, but didn’t repeat his previous sins. He went on a kind of listening tour, making the rounds of small Democratic gatherings around the state.

Andrew won easily. But victory didn’t prove the catharsis he’d hoped. For the son of a governor, attorney general was a consolation prize. Spitzer looked like a lock for eight, maybe twelve years. “Andrew sat in that nondescript office thinking, I’m going to be in purgatory for a long time,” says a person close to him during that period.

Then, after the banks almost failed—and as they came back, with taxpayer help, as lucrative as ever—history gave Andrew a role to play. There were echoes of his rabble-rousing father, and also of Spitzer, who’d found in Wall Street a worthy villain. But there was also something of Andrew’s own, that arrogance and anger harnessed to a cause larger than his ambition. Andrew delightedly grabbed the headlines, going after Madoff enablers, school-loan hustlers, Merrill Lynch, Bank of America, as well as the AIG bonuses, sometimes prosecuting but always taking names that usually filtered into the press. A few complained that some of the publicity merely burnished his image—and needlessly embarrassed his targets—particularly when the charges didn’t go anywhere. Clearly, though, Andrew’s office was effective: He is widely credited with ferreting out deep-rooted corruption in the New York State pension system, for instance.

In the meantime, Spitzer’s political career had started to crumble, a phenomenon that began slowly and ended with stunning speed. An early blow had been allegations that, as governor, he’d used state officials to spy on his political opponent. Andrew and Spitzer had long disliked each other—perhaps they were too alike. Spitzer had been born wealthy, and so each in his own way was a child of privilege with something to prove. Andrew’s office had quickly produced a report critical of Spitzer, undisclosed elements of which dribbled out in the papers from Syracuse to New York City over several days, always citing anonymous sources. Andrew delighted in Spitzer’s trouble. “Eliot hears my footsteps,” he confided at the time. Then Spitzer’s identity as Client 9 was revealed, prompting his resignation in a prostitution scandal. Spitzer’s successor, David Paterson, proved ill-equipped for the job, and Andrew, showing newfound restraint, stayed out of the spotlight as Paterson was pushed aside—the world did seem to work on Andrew’s behalf. “He was reborn,” says a person close to him at the time.

Andrew has abandoned few of his father’s broad goals—they’re both pragmatic progressives who believe government can be an instrument for good. But the son is a man of his era. “My father liked the concept of people,” Andrew says with that laugh, at once loving and dismissive. “I like people.” Mario wanted to inspire from the podium. “He would say, ‘My mission was to lead, to communicate a vision,’ ” says Andrew. Andrew sees himself differently—he operationalizes. He’s not speaking directly about his father, but the undercurrent is unmistakable when Andrew tells me, “A thought without action is hollow at the end of the day.” Andrew has found other role models, like Bill Clinton—and Matilda. “My mother is a real people person. She’s much more comfortable with emotion [than my father],” he says. “She’s a natural retail politician.” Andrew has taught himself to work a room. “He can make you feel like you’re the only person in the world,” says a person who worked with him. “It’s similar to a Bill Clinton thing. It feels sincere.”

The competing Andrews are still there—a do-gooder with lofty goals, and the Prince of Darkness who will win at all costs. “Fuck them if they’re not with us by now,” his aides have been heard to say. “He has no qualms about misleading reporters, pressuring them, playing favorites,” says a person who has worked with the Cuomo camp. “It’s a game to him. He thinks he’s good at it, and he is.”

Andrew has compiled an impressive 224-page treatise of his policy positions—pro-choice, pro–gay rights, anti–death penalty, among others—but in this economy, that’s mostly window dressing. His priorities are, of necessity, the same as those of all recent governors: Clean up Albany, get the state’s fiscal house in order, right-size government. The current record budget deficits will make austerity more palatable, as Andrew knows, and he has intimated that layoffs of state workers may be a dramatic early step. Mario expanded social programs because he believed that was the right thing to do, even if it meant raising taxes to some of the highest levels in the country. Andrew believes taxes are too high, and will be faced with cutting programs cherished by his father. Whereas Mario increased Medicaid spending by two thirds, Andrew has pledged to trim the cost of the health-care program for the poor, which now accounts for an estimated 38 percent of the state budget. “Andrew will be elected to dismantle a lot of what his father helped build,” says a member of the Cuomo camp. And his father’s old Democratic colleague, Assembly speaker Sheldon Silver, is likely to resist Andrew’s efforts and, as the Cuomo source says, “to quote Mario in doing so.”

To some, Andrew’s style brings to mind Spitzer, who faltered even before the scandal. Both can be bullying and self-righteous. “Andrew is as angry as Eliot,” a disillusioned former Spitzer aide told me. “He’ll self-destruct, too.” But the newly self-aware Andrew has thought about this and rejects the comparison. For Andrew, Spitzer was as subtle as a hammer, viewing every problem as a nail. Andrew is an experienced political operator who sees himself as more emotionally mature than Spitzer (and than the angry 24-year-old he was) and who believes, like his model Clinton, that he can mobilize political will, pushing voters while pressuring politicians. Like Spitzer, he is running against a dysfunctional Legislature. But here, too, Andrew believes his approach is subtler. Spitzer took on legislators directly, sometimes denouncing them in their own districts. Andrew has recently launched a TV-ad campaign to rally voters, urging them to petition their legislators to cap property-tax increases.

This time around, Andrew is a better gubernatorial candidate. In part, he says it’s because he’s found a measure of peace: “I’ve already lost. What else can they do to me?” In part, it’s because he’s more disciplined, his aggressive side carefully kept from public view, one luxury afforded by a 2-1 lead in the polls against a weak Republican field. Though he recently took his girls upstate on a campaign-fishing trip—both offering photo ops—he seldom grants extensive on-the-record interviews. “He is running to not make mistakes,” says a friend.

These days, much of Andrew’s life seems designed to keep risk at bay. His personal life has rebounded. He’s got a live-in girlfriend, Sandra Lee, who’s smart, photogenic, and unthreatening. “What you see is what you get,” says an occasional Cuomo confidant. She’s a successful down-market Martha Stewart who created the Semi-Homemade brand, which includes recipes to help the busy homemaker whip up meals from ready-made ingredients—Matilda has been known to shudder at Lee’s lasagne, made from canned tomato soup and cottage cheese.

As successful as Lee is—and she presides over a mini-empire, including a Food Network show—she does not contest Andrew for the distinction of crusader. (Once, when one of Kerry and Andrew’s children said Daddy would fight for civil rights, Kerry corrected her: Daddy and Mommy.) “I leave politics to Andrew,” Lee has said. Lately she mostly talks to the press about StarKist tuna, for which she is a spokesperson. “She is fun and smart and nice. Fundamentally nice and good,” Andrew tells me, a compliment that mostly highlights what she isn’t. She isn’t interested in marriage, and she isn’t prone to nasty personal battles, which Andrew has pledged to avoid. “Nice and good is important,” he says.

And then there is his father. Several years ago, a colleague of mine asked Andrew what play or opera best represented his relationship with his father. Andrew replied, “The story where the father chains the little boy to a chair. In the basement. And leaves him without food. And then beats him.” Andrew was joking, of course, but it’s a telling joke. Father and son are still at friendly loggerheads. “I like people. [Staff] would try to drag me away from people,” Mario insists, despite what Andrew thinks. When I wonder if he operationalized, he first says, “I don’t understand the word”—Andrew made it up, after all. Then he adds, “You can’t be the governor without operationalizing.” But these days the father-son relationship is mostly “sweet,” Andrew says.

“Andrew has long wanted to assert and affirm himself and be affirmed,” says a Cuomo-family friend. Lately Mario affirms: “Andrew could accomplish anything he wants.” As the friend says, “Mario hates being pushed off the stage.” But both acknowledge the new order of things. “My father wants to do whatever I want him to do,” says Andrew. “It’s come full circle. He now helps me the way I helped him.” Mario will even admit that Andrew is the better politician—though he quickly affixes an asterisk to the scorecard: If Mario had come after Andrew and benefited from his tutelage, then he’d be the better politician.

Additional research by Bryan Hood