The morning after election day, I went for a jog and ran into Chuck Schumer. This was November 2002, however. The White House was fanning fears of Saddam Hussein, nuclear madman. The antiwar movement was growing. There had been considerable media hype about the Democrats’ making big gains in the House and the Senate in the midterm elections. In the city, especially, there was a hunger for Democratic revenge against George W. Bush.

But that morning-after brought shock: The Dems had lost their Senate majority. On the House side, Bush became the first Republican president ever to gain seats in an off-year election. Karl Rove was still a genius back then.

My random running route took me down Prospect Park West, in front of the stately apartment building that is Schumer’s New York home. Just as I passed under his building’s entrance canopy, the senator came out of the lobby and headed for his waiting car. At the same moment, a woman walking by spotted Schumer and yelled, in an aggrieved tone, a tone of Democratic horror, “Chuck, what happened?”

Schumer’s mouth curled in sympathetic disgust. He turned both his palms up, in the classic New York waddayagonnado? gesture. And he shrugged, slowly and deliberately, drawing out his silent but clear response: “Ya got me!” Schumer appeared as helpless as any other Democrat.

Not this time. Schumer spent Election Night 2006 in D.C., mostly inside his command center, a suite at the Hyatt, ordering up last-minute robo-calls and trying to restrain his jubilation. It was the final act in the complete Schumerization of the Democratic Senate campaign. His bare-knuckle savvy and noodgy relentlessness, so familiar locally as to verge on self-parody, paid historic national dividends for the party. “The Democrats obviously won big in the House, but there was no Gingrich or Rove behind it—no guru,” a Democratic political consultant says. “Sure, Rahm Emanuel was in charge, and he did a good job, but Bush won the House for the Democrats more than Rahm did. The Senate, though? That was all Chuck.”

When Schumer accepted the job as head of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee in late November 2004, Bush’s approval rating was a solid 53 percent. “Our goal then was preserving North Dakota, Nebraska, and Florida and keeping the Democrats at 45 seats,” Schumer says as the astounding returns start rolling in. “Our worries were not about winning Missouri or Tennessee.” Yet Schumer went on offense from the beginning, in ways large and small: He enlisted his vaunted Wall Street fund-raising contacts, ultimately hauling in $113 million—$23 million better than Elizabeth Dole did for the GOP Senate candidates—with $23 million of the cash coming from New York donors. He pleaded with red-state incumbent Dems not to retire. Schumer picked candidates. Then he hectored them into staging Schumer-style press conferences on slow-news Sundays.

Some of the tactics were not pretty. Schumer screamed at Howard Dean to cough up some DNC cash. He recruited and then ruthlessly dumped an Iraq-war vet in the Ohio Senate race when he decided, correctly, that Sherrod Brown had a better chance to win. Schumer certainly got plenty of help along the way—from Mark Foley, from Michael J. Fox, and most of all, from Bush’s ineptitude in managing the war. But nearly every one of Schumer’s moves worked. Even he was surprised. “We pulled an inside straight,” he says.

So now that Schumer is a kingmaker, what’s in it for us? A Hillary Clinton presidential run will only solidify Schumer’s role as New York’s dominant congressional presence, with House Ways and Means chairman Charlie Rangel a close second (besides realigning the tax system and steering money to the city, Rangel is talking about two other initiatives that would benefit New York: a push against illegal guns and a focus on anti-poverty programs). Schumer says his top legislative priority is restoring a $4,000-per-family college- tuition tax deduction that he co-authored in 2001, only to see it killed last spring, when the Republicans instead handed $5 billion in tax breaks to the major oil companies. “We’re gonna roll those back,” Schumer says. “I’m also going to focus on delivering more homeland-security and transportation money for New York.” (Speaking of anti-terrorism money, Mayor Bloomberg was the only major New York pol to back Joe Lieberman, who may chair the Senate’s Homeland Security committee.) Whether the people Schumer brought to the Senate are good for New York remains to be seen: Several ran as anti-globalization, anti- immigration Democrats.

And what does Chuck want for Chuck? He’ll wield more power on the Banking and Judiciary committees; he’ll move up to chairman of the subcommittee on courts, meaning he’ll get to vet every Bush nominee. He’s agreed to run the DSCC again, through 2008. “Whenever you have some success in politics, always the question is, ‘What’s next?’ ” he says, laughing. Majority Leader? President? “I love being senator,” he says.

True, no doubt. But before the string section starts playing, let’s remember one great irony: This triumph of New York chutzpah, this golden moment of Democratic harmony, grew from a good old New York sharp-elbowed feud.

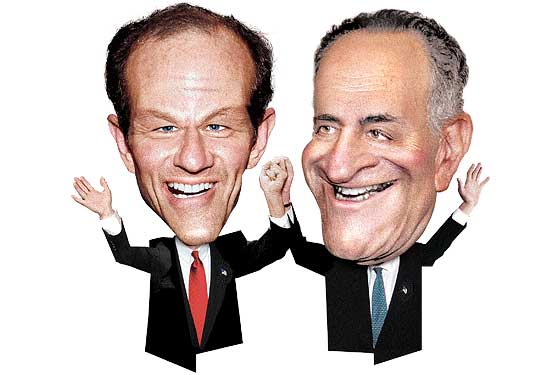

A mere two years ago, Schumer was unhappily stuck in what looked like a permanent congressional minority and very publicly began mulling a run for governor. Throughout the fall of 2004 dangled a tantalizing prospect for the New York political media: Chuck Schumer versus Eliot Spitzer in a state Democratic primary, a war between two intensely smart men who genuinely disliked one another. The preliminary sniping was by turns comical and nasty.

Alas for entertainment’s sake, the full battle was never joined. Many insiders believed Schumer’s interest was a ruse all along, a maneuver to boost his Senate stature, with the DSCC job one reward for not running for governor. Yet as a direct result of the Schumer-Spitzer rivalry and the race that wasn’t, New York has reaped a political windfall that was inconceivable in 2004. “I think,” Schumer says now, as the Montana and Rhode Island Senate seats have fallen improbably into Democratic hands, “that I made the right choice.”

“Bush won the House for the Democrats more than Rahm did,” says a consultant. “The Senate? That was all Chuck.”

The guy who ended up running for governor on the Democratic line had a pretty good Election Night too. But as Spitzer giddily piled a quotation from Whitman on top of lines from TR on top of a yawp from Jim Cramer, the holding pen beneath him in a ballroom of the midtown Sheraton filled with lobbyists and moneymen and legislators-for-life, the very crux of the Albany mess. All of them Eliot’s new best friends.

The politician working the TV cameras the hardest was State Assembly Speaker Sheldon Silver. He gassed on about how much he’d been chatting with Spitzer lately, how the two men were looking forward to working hand in hand—never mind Spitzer’s rhetoric about demolishing Albany’s culture of dysfunction. When it got to the particulars, things were less chummy. Silver vigorously defended Alan Hevesi, whom Spitzer has declared too compromised to continue as comptroller. Silver says his top priority is resolving the lawsuit over state education funding—an item Spitzer is indeed also highlighting. But Spitzer and Silver are determined that the city pay as much as $1 billion into the settlement pot, a formula Bloomberg angrily dismisses. More palatable to City Hall, however, might be a high-stakes swap: The state picks up the share of Medicaid expenses currently billed to localities in exchange for the city’s eating a bigger portion of the education budget. Such a deal would also lift the Medicaid burden from upstate counties, making it an easier sale in the State Legislature. (How fossilized is that legislature? Two indicted incumbents were reelected. And on a day that saw a Democratic tidal wave everywhere else, one Republican out of 35 in the State Senate was defeated. One!)

Spitzer talked throughout the campaign about reforming the state’s wildly expensive health-care system. One interesting sign that he’s deeply serious was an absence from the Election Night festivities. Spitzer’s list of endorsers was staggeringly long, and included most of the state’s deeply entrenched special interests. Except for one: SEIU/1199, the powerhouse health-care-workers union. Dennis Rivera, its president, helped seal the 2002 reelection of George Pataki by cutting a deal for $1 billion in raises for 1199’s members. And the union’s early endorsement of Andrew Cuomo—backed up by the loan of Jennifer Cunningham, 1199’s shrewd political director, to Cuomo’s campaign staff—was the key to Cuomo’s winning the attorney-general race this year.

Yet when 1199 offered to endorse Spitzer, complete with a press conference attended by Rivera, Spitzer turned it down. The rejection buffed Spitzer’s image as a reformer during the campaign; we’ll see if it makes cutting health-care spending any easier.

Albany’s permanent government hasn’t exactly been quaking at the sound of Spitzer’s campaign slogan, “On day one, everything changes.” “We’re considering making T-shirts,” one union leader says confidently, “day two: still here.” Which is why it’s fine for Spitzer to talk of compromise and cooperation now. But real change will require the same hard-ass attitude he’s shown Wall Street, Alan Hevesi, and Chuck Schumer.

E-mail: Chris_Smith@nymag.com.