In January of last year, Elizabeth Warren went on The Daily Show and did what was then, and still is, that rarest of things: She gave a cogent, compelling, almost crystalline account of the financial collapse. It wasn’t the first time she had delivered this story, but her task seemed particularly urgent that night. A Republican named Scott Brown had just won Ted Kennedy’s old Senate seat, depriving Democrats of a filibusterproof majority and prefiguring the bloodbath the party would take during the midterms. Barack Obama had been in the White House for a little more than twelve months, and already it appeared that he was losing control of the political narrative.

Warren tried to wrest it back. The problems started not with Obama, she said, but in the eighties, when the financial regulations that had been put in place after the Great Depression began to be repealed. This allowed “the big financial firms, the titans of Wall Street,” to “start selling ever more dangerous mortgages, ever more dangerous credit cards, ever more dangerous car loans,” which they then repackaged and sold again, producing, in addition to huge profits and bonuses, huge risk. After the market took a downturn, “all that risk that’s been built into the system starts to come home, somebody’s got to pay,” and “those same CEOs on Wall Street basically turn around to the American people and say, ‘Whoa, there’s a real problem here, and you better bail us out or we’re all gonna die.’ And so we did, that was TARP. And now we’re about to write the last chapter in this narrative.”

The story could have two endings, Warren said: one that favored “the CEOs on Wall Street” or one that turned out okay for the rest of us. “This is America’s middle class. We’ve hacked at it and chipped at it and pulled on it for 30 years now, and now there’s no more to do. Either we fix this problem going forward or the game really is over.” Jon Stewart, who had mostly kept quiet during Warren’s spiel, seemed momentarily shocked. “I know your husband is backstage,” he told her, “but I still want to make out with you.”

It was performances like that one that helped propel Warren, a Harvard law professor who was then chairing the congressional panel that oversaw TARP, higher into the political firmament. And as Obama’s star waned in the eyes of many liberals, hers rose in inverse proportion. That the story Warren was telling seemed increasingly destined to end more as she’d feared than as she’d hoped only served to boost her standing. Warren’s remarkable powers of explanation—and her willingness, even eagerness, to take on Wall Street—were precisely the qualities that the president seemed to lack and precisely what so many liberals were yearning for. “What Liz can do, maybe better than anyone walking the Earth, is talk about financial markets and the complexities of our economic system in a language that people understand and that resonates with them,” says Jared Bernstein, a former economic adviser to Joe Biden.

Warren was so good at this that, although she was relegated to the fringes of the bureaucracy—first running the relatively toothless TARP PANEL and then advising Obama on getting the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau off the ground—she cut the public profile of a cabinet official. Stewart, Charlie Rose, and Bill Maher frequently invited her on their shows to talk about the economy; online petitions urging Obama to appoint her head of the CFPB garnered hundreds of thousands of signatures. Warren’s ubiquity became a sore spot for some Obama officials, who especially didn’t appreciate the fact that she was often as willing to criticize Democrats as Republicans. Her public grillings of Treasury Secretary Tim Geithner when he appeared before her TARP panel—“A.I.G. has received about $70 billion in TARP money, about $100 billion in loans from the Fed. Do you know where the money went?”—were political theater at its finest.

The result is that now, in large swathes of blue America, Warren’s star actually eclipses Obama’s. Her announcement in September that she would run for the U.S. Senate—that she would seek to take back the seat Scott Brown won in 2010—has been greeted by Democrats with the sort of passion and energy not seen since that heady night in Grant Park three Novembers ago. A grainy YouTube video of Warren speaking in a supporter’s living room became such a viral sensation that the Washington Post columnist E. J. Dionne Jr. deemed it “the declaration heard round the Internet world.” And while the presidential race is undoubtedly the most important election of 2012, Warren’s campaign is shaping up to be the most anticipated, as it affords liberals a chance to prove that the path that Obama pointedly did not take—the story he failed to tell for so long—can win at the ballot box.

As a political icon, Warren may be without equal these days, but as a political candidate, she’s still a novice. When I recently asked her to make the case against Brown, the sure-footedness she’s displayed on so many occasions suddenly deserted her. “This race is about America’s future, it’s about a choice,” she began confidently, before settling into a long, uncomfortable pause. She eventually continued, “Uh, uh, gosh, I know candidates are always supposed to have the great ten-second clip on how this works. Kyle”—she said, referring to her spokesman, Kyle Sullivan, who was sitting in on the interview—“is probably gnashing his teeth right at this moment. But”—she paused again—“it’s about whose side you stand on. Scott Brown is one of Wall Street’s favorite senators. Um, that’s not what I—I want to go to Washington—let me say it differently. Scott Brown’s one of Wall Street’s favorite senators. I want to go to the United States—I want to go to Washington to be the middle class’s favorite senator. Or the favorite senator of the middle class. Maybe that’s easier without the possessive.”

I asked Warren if there was anything besides Brown’s Wall Street ties that made her want to take him out. “There are surely other areas,” she replied, “on environmental issues, on the DREAM Act, on”—she hesitated again—“family issues.”

Like abortion?

“No, no, around LGBT,” Warren said. “ ‘Don’t ask, don’t tell’ was how it was framed, but there’s a whole, I hate to do it as just ‘don’t ask, don’t tell.’ Just kind of around the whole, you know, defense of marriage.” She sighed. “I’ll learn the way that politicians talk about these.”

The way most Democrats in Massachusetts and Washington talk about Brown is with thinly veiled contempt. His very presence in the Senate—coming about as it did through a special election necessitated by Kennedy’s death and against an inept opponent in Martha Coakley—is viewed as both a fluke and an affront. The mere fact that he now has to run in a regular election, much less one that’s taking place in a presidential year, when the Democrats’ three-to-one advantage in registered voters in Massachusetts should be particularly potent, is making Democrats confident, if not downright cocky. “We could put up Bugs Bunny against Scott Brown this year,” says one Massachusetts Democratic strategist, “and it’d be a closer race than he had last time.”

But unseating Brown may not be so easy. Since he arrived in Washington as a tea-party hero, he’s done a masterful job of rebranding himself. Although he generally votes with Republicans, he’s sided with Democrats enough times on high-visibility issues—including “don’t ask, don’t tell” and the Dodd-Frank financial-reform legislation (although only after earning concessions for big Massachusetts banks)—that he touts himself as “one of the most bipartisan, if not the most bipartisan, senator there.” Just last week, he announced that he was opposing the top legislative priority of the National Rifle Association. “He’s trying to position himself as the third woman from Maine,” says Jack Corrigan, a veteran Massachusetts Democratic consultant, referring to those models of moderation, Senators Susan Collins and Olympia Snowe. And then there’s Brown’s personal appeal. Despite his time in Washington, he hasn’t ditched the pickup truck and barn jacket that came to define his 2010 race.

The contrast between the Massachusetts Everyman and the Harvard Professor is one that Republicans are eager to make—and one that Warren’s campaign has spent much of its time trying to rebut. Indeed, Warren’s advisers can be almost paranoid about how she is portrayed. When another reporter recently went to interview Warren at the house she shares with her second husband, a fellow law professor, Warren’s campaign allowed it only on the condition that the house itself—a restored Victorian a few blocks from Harvard Square that, according to financial-disclosure forms, is valued between $1 million and $5 million—was off the record.

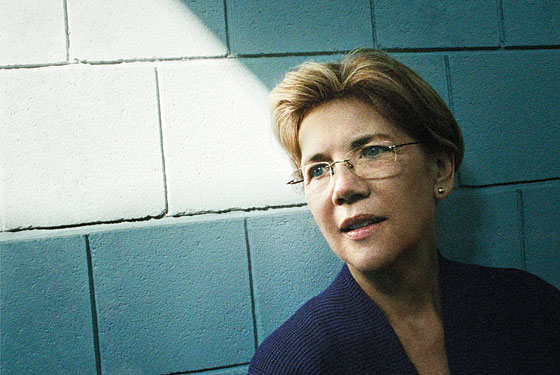

Warren, who is 62 years old with big blue eyes, a blonde bob, and a wardrobe of cardigans and turtlenecks, looks every bit the professor. But she’s quick to note that she “wasn’t born at Harvard.” One evening last month, she stood in the dining room of a supporter in the Jamaica Plain neighborhood of Boston, introducing herself to a mostly young and professional crowd, and the first thing she chose to talk about was her humble roots. “I grew up in a family that was kind of hanging on to its place in the middle class by its fingernails,” she said of her childhood in Oklahoma City. “I started waiting tables when I was 13. I got married when I was 19. I graduated from a public university, and I went to work then teaching in public elementary school, working with special-needs kids. My first baby was born when I was 22.” The distance she’d traveled seemed a genuine source of wonder to her. “From being the daughter of a maintenance man to a fancy-pants professor at Harvard Law School,” she said, her voice cracking. “America is a great country.” The crowd chuckled, but Warren didn’t mean it to be a punch line. “I really believe that,” she insisted.

Warren’s Okie upbringing is the kind of backstory that any candidate would try to exploit, but it’s actually her academic career that may prove to be more politically potent. Far from being an isolated denizen of the ivory tower, Warren has long approached her scholarship with a crusading quality. Time and again, she’s been able to distill very complex economic data into simple stories—and not just stories about good and bad luck but almost biblical tales of malfeasance, with villains and victims. “Academics are always very happy to say other people are wrong,” says Jacob Hacker, a Yale political scientist who’s collaborated with Warren. “But Elizabeth would say they’re not just wrong, they’re bad people.”

In 1981, as a young professor at the University of Texas law school, Warren helped conduct an empirical study of people who file for bankruptcy. “I set out to prove they were all a bunch of cheaters,” she once recalled. Crisscrossing the country, often with a portable photocopier strapped into the airplane seat next to her, Warren visited countless courthouses, where she pored over records and interviewed judges, lawyers, and often the debtors themselves. What she found contradicted her assumptions: Most bankruptcy petitioners weren’t deadbeats at all but rather middle-class families that had hit a rough patch. Over the next decade, Warren built on this work, marshaling a series of studies to paint a picture of an increasingly vulnerable middle class.

Warren became the senior adviser to the National Bankruptcy Review Commission in 1995, the same year she arrived at Harvard. Congress, at the behest of the financial industry, was debating whether to tighten bankruptcy rules so that it would be harder for individuals to file, and it fell to Warren to explain how much of a burden this would place on struggling families. “It was hard to be in the politics of it,” she recalls. “I remember people saying, ‘You look like you’ve lost weight.’ It was new ways of throwing elbows and exercising influence.”

Warren was a frontline combatant in what she calls “the bankruptcy wars” for ten years, until finally, in 2005, her side lost: Congress passed the legislation (which would later become a precipitating factor in the subprime debacle). But the experience taught Warren a lot about how Washington operates. “Bankruptcy is a complicated law to explain, and most people don’t see themselves as potentially future bankrupts,” she says. “It was easier for [the financial industry] to keep the fight on a bumper-sticker level.” She made sure that the next time she entered a public fight, she’d have tightened her message.

“I woke up at three o’clock in the morning and realized the answer I gave you was terrible.”

That opportunity came soon enough. Throughout the Bush-era housing boom, she saw warning signs of coming financial ruin. “I was a crazy person by the early 2000s,” Warren recalls. “I’m saying, ‘This can’t last, we are building so much risk into the system, family by family by family, it will explode.’ ” In 2007, she proposed the creation of a “financial-protection safety commission.” “It is impossible to buy a toaster that has a one-in-five chance of bursting into flames and burning down your house,” she wrote in the journal Democracy. “But it is possible to refinance an existing home with a mortgage that has the same one-in-five chance of putting the family out on the street—and the mortgage won’t even carry a disclosure of that fact to the homeowner.” It was an irresistibly intuitive framing device, and one that Warren has, over the last four years, been able to leverage to such an astonishing degree that it’s difficult to think of anyone in Washington who’s enjoyed so much influence while wielding so little actual power.

Warren’s proposal was ultimately part of the Dodd-Frank legislation, which established the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. She spent the next year overseeing its creation. Warren was certain that the simpler and more transparent she could make the bureau the more public support she could build for it. She promised to use “crowd-sourcing” technology so that consumers could tip off the CFPB about deceptive financial practices, and she posted her daily schedule—complete with coffee breaks—on the bureau’s website. By this summer, Warren had figured out how to make even plumbing a communication tool. She successfully lobbied to locate the newly created CFPB in a building right around the corner from the White House, for maximum public visibility, and she was particularly obsessed with adding restrooms and water fountains in the lobby. “Every Boy Scout troop [leader] in America will know that’s the place you can take the boys after they’ve had their pictures taken in front of the White House,” she explains.

Of course, there’s another Democrat who came to prominence at roughly the same time as Warren and who also rose to power using his phenomenal gift for storytelling. Warren first met Obama in 2003 at a fund-raiser one of her Harvard Law colleagues was hosting for the then-unknown Illinois state senator, who proceeded to dazzle Warren with his knowledge of her own work. “You had me at ‘predatory lending,’ ” she remembers saying to him. But in retrospect it’s telling that, four years later, it was John Edwards who was the first Democratic presidential candidate to embrace her CFPB proposal and make it part of his platform.

Obama, as president, ultimately pushed for the creation of the CFPB—and tasked Warren with getting it up and running—but Warren was a bad fit for the administration from the start. She frequently found herself at odds with Geithner and Larry Summers, telling Charlie Rose in 2010 that “they see the world from a top-down perspective.” Meanwhile, Warren was also out of step with behavioral-economics disciples like Cass Sunstein, who believe that government works best when it “nudges” people’s decisions rather than mandates them. Warren favors far more traditional command-and-control regulatory approaches. “Elizabeth is fine with a nudge,” says Adam Levitin, a Georgetown law professor and Warren protégé, “but she also knows that sometimes you need a sharp elbow, and she’s not afraid of that.”

Most important, the Obama team that had been so good at uplift during the campaign never could get a firm grip on how to talk about governing. Obama tuned out Warren’s Manichaean view of Wall Street. “He meets with bankers,” she complained to Confidence Men author Ron Suskind. “He doesn’t meet with me.” Her biggest difference with Obama was over whether she’d be nominated to head the CFPB, a fight that the administration, given Republican opposition to Warren, was pretty sure it would lose. Congressman Barney Frank says he advised Obama that nominating Warren to head the CFPB was “a win-win, because if the Republicans filibuster her, they’ll make her a hero who can run for the Senate, and because of that, to avoid her being a Senate candidate, you might get them to confirm her.” But the White House didn’t have the stomach for such a confrontation and ultimately concluded that the CFPB nomination would have to go to one of Warren’s deputies, Richard Cordray (who himself, it should be noted, has yet to be confirmed owing to GOP opposition).

It’s only now, after Warren has left Washington and launched her own political career, that Obama has appeared to heed her advice, taking a much more populist tone in recent months. “If you listen to the story that Obama is telling about the economy right now,” says Jared Bernstein, “it strikes me as very similar to the story that Liz is telling.” If Warren sees any irony in this development, she’s careful not to show it.

“Our job is to let Elizabeth be Elizabeth,” says Doug Rubin, “and to build a campaign around her.” A former top adviser to Massachusetts governor Deval Patrick, Rubin is now Warren’s chief political strategist. When I met him recently at his Boston office, copies of The Tipping Point, Moneyball, and The Art of War were stacked on his desk, while Scott Brown’s memoir Against All Odds sat on the bookshelf. Rubin has worked in state politics for two decades, but the first time he ever spoke to Warren was this past summer, when she called him on a Sunday afternoon to pick his brain about a potential Senate race. “Normally when I talk to people who are thinking about running for office, it’s all logistics: How much money am I going to have to raise? How much time will I have to be out on the trail?” he says. “But she spent the first half-hour talking about why she wanted to do it, the issues she cared about. I was very impressed by that.”

By the time of Warren’s conversation with Rubin, she’d already been the focus of an intense, months-long lobbying effort by some of the Democratic Party’s biggest names to get her to join the race. It began in earnest in March after Guy Cecil, the executive director of the Democratic Senatorial Campaign Committee, went to Boston to meet with all of the Massachusetts Democrats contemplating a run against Brown. For Cecil and the DSCC, no 2012 Senate race was more important than Massachusetts—the bluest state currently represented by a Republican. But none of the candidates whom Cecil met seemed capable of beating Brown. So when he returned to Washington, the DSCC commissioned a poll of Massachusetts voters that included Warren’s name, biography, and political positions. When the poll found Warren and Brown in a statistical dead heat, the DSCC had its preferred candidate, and three senators—Patty Murray, Harry Reid, and Chuck Schumer—were tasked with the job of persuading Warren to enter the race.

Murray talked about the importance of having more women in the Senate. Reid made the case about preserving the Democrats’ Senate majority. And Schumer, over dinner at a Washington restaurant, appealed to Warren’s more basic instincts, casting the race as an opportunity for her to exact revenge on the Republican senators who’d prevented her from helming her beloved CFPB. It didn’t seem to matter that some of Warren’s suitors had previously clashed with her and would presumably clash with her again—Reid, for instance, voted for the 2005 bankruptcy bill, while Schumer’s close ties to Wall Street led one close Warren adviser to dub him “the senator from Bankistan.” “Their only test is, ‘Can she help us hold on to the majority? And once she gets here, she may be a pain in the ass, but we’ll figure it out,’ ” says one senior Democratic aide. “Their diametrically opposed worldviews will stay below the surface until 2013.”

Meanwhile, the White House was also lobbying Warren to run. It didn’t want her final act to be getting passed over for the CFPB job—if only because it didn’t want her legions of liberal admirers to be any more angry at Obama than they already were. Having Warren run for the Senate was a much more uplifting next chapter, and several of Obama’s advisers, including David Axelrod and Pete Rouse, encouraged her to take the plunge. Indeed, Axelrod eventually played a key role in connecting Warren with Rubin, with whom he’d worked on Patrick’s 2006 gubernatorial campaign.

In August, Warren moved back to Massachusetts and, working with Rubin, began to lay the groundwork for her campaign. Her first major step was to hold a series of house parties around the state. Rubin had envisioned relatively low-key, press-free affairs that would allow Warren to meet with local Democratic activists and get her campaign sea legs. But the house parties quickly turned into something else entirely. Within a week, hundreds of people were turning out to hear Warren speak. When she showed up at an event in Western Massachusetts, she was greeted by an avalanche of homemade signs urging her to run.

No house party would become as significant as the one that a Democratic activist named M. J. Powell hosted in Andover in mid-August. When Warren officially announced her candidacy, on September 14, she did so with a web video, produced by the veteran Clinton consultant Mandy Grunwald, that had its populist moments (“Washington is rigged for big corporations that hire armies of lobbyists”) but, with its soft lighting and heavy focus on her upbringing, also came off as overly polished. Four days later, a Warren supporter named Anne Jones—who, unbeknownst to the campaign, had filmed Warren’s talk at the Andover house party—posted her own video on her YouTube channel that, until then, had only featured instructional videos about organic gardening. This was the Warren video that went viral.

“There is nobody in this country who got rich on his own. Nobody,” Jones’s shaky camera catches Warren saying. Every successful businessman hires “workers the rest of us paid to educate” and moves his goods “on the roads the rest of us paid for.” More notable than her argument, though, is Warren’s tone—at turns angry, sarcastic, and, above all, uncompromising. “You built a factory and it turned into something terrific or a great idea—God bless, keep a big hunk of it. But part of the underlying social contract is you take a hunk of that and pay forward for the next kid who comes along.”

Not since Obama in 2008 has a candidate seemed so perfectly matched to the public’s mood. “With Obama, people were tired of partisanship, and they were looking for a grown-up,” says one Democratic strategist. “This cycle, voters are pissed off. They’re not just looking for change, they’re looking for retribution, and she’s giving them a chance to have that.”

Within weeks, Warren had raised a staggering $3.15 million and essentially cleared the Democratic field of all challengers. In fact, Warren’s momentum is almost too great. On the night of the house party in Jamaica Plain, she fielded a question from a supporter who was frustrated that he was having a difficult time volunteering for her campaign. “This has happened so fast, we actually have not built the structure around it,” Warren apologized. “Instead of having a runway, I feel like a Harrier jet.”

In some ways, Warren’s campaign is not only a referendum on the last three years—but a chance to do them over. “I’ll just be blunt, I thought the whole fight was 2008,” she says. “We’d put sensible people in place, we’d write sensible rules, and we’d spend 50 years rebuilding America’s middle class.” The question that hangs over Obama—and the entire Democratic Party, for that matter—is why that didn’t happen. Warren believes the answer is that the political system, such as it’s currently constructed, simply didn’t allow for it. Unlike Hillary Clinton, the last politician who ran for Senate after having built such an outsize national reputation, Warren doesn’t seem terribly concerned about fitting in or diminishing her profile once she gets there. “If the notion on this is we’re going to elect somebody to the United States Senate so they can be the 100th least senior person in there and be polite,” she says, “and somewhere in their fourth or fifth year do some bipartisan bill that nobody cares about, don’t vote for me.”

She insists that she won’t play by the normal Washington rules, if only because she’ll have no incentive to do so. “I’m not looking for my next job,” she told me. “I figure that is the biggest liberator in Washington humanly possible … I’m not going—and I want to be careful here, I don’t want to do this in juxtaposition to Hillary or anybody else—I’m not going so that I can create a long and illustrious career in the Senate. I’m going to make change.”

But first, of course, she’ll have to beat Brown, who’s spent the last two years preparing for this sort of challenge. As foils go, bank executives and smug Treasury secretaries look a lot more villainous than a guy in a barn jacket. “He’s not a particularly Wall Street figure,” concedes Barney Frank. Which is why Warren would be smart to stick to the larger themes that have already served her so well. “The best Senate campaigns are the ones that take on the nature of a crusade,” says former Obama adviser Anita Dunn, “when a race takes on a level of meaning for people that is more than mere politics. Elizabeth has that potential to be one of those transcendent candidates.”

One recent evening, while she was sitting in a booth at Doyle’s bar in Boston waiting for her order of fried shrimp to arrive, I asked Warren about her transcendent qualities—or at least why she thought that YouTube video from the Andover house party had gone viral. “Because it was right,” she replied. “Because people said, ‘Oh, that’s something we haven’t talked about.’ If I state it in a way that helps other people state it as well, that’s what advancing a conversation is about.”

The next day, though, after Warren had taken a tour of a fish-processing plant in Gloucester, she sought me out in the parking lot. “I woke up at three o’clock in the morning and realized that answer I gave you about the video was terrible,” she said. “Conversation is the wrong word.” She was running to a meeting and had to go, but a few days later, I got Warren on the phone so she could give it another shot.

“It’s so much more than just a conversation,” she said. “I found myself thinking in the middle of the night, what a bland description of a powerful—” She paused. “God, this is the problem, I can’t think of a better word to describe it. Of a powerful moment. We’re talking about the future of our country. People stop me on the street and say, ‘Oh my gosh, you’re Elizabeth Warren!’ and I say ‘Yes!’ And then they’ll say, ‘I’ve got a good job, but I have a son who graduated from college fifteen months ago and has more than $100,000 in student-loan debt, and he can’t get a job. Please help us. Thank you for running.’ To call that a conversation, I just was thinking to myself, it misses the heart of what’s going on here.” She paused again, searching for another anecdote that might get her point across. “A woman came up to me at an event and said, ‘I have two master’s degrees and I’ve now been out of work for 22 months, I’m in my fifties, and I’m not sure I will ever get a real job again. What’s happened to America?’ ”

“That was the kind of thing,” Warren told me. “I just felt like, I didn’t give enough of the heart of what’s going on here. That was my three-in-the-morning thing. And tomorrow morning at three o’clock, I will think of something else.”